Ever since the invention of the movie-camera, danger has always served as a core ingredient of cinema. The very nature of its original form is a recipe for disaster, a highly flammable nitrate film-base, used from the time of its invention in 1888 all the way into the early 50s. For whatever reason, when it comes to art or entertainment, our necessity for danger can sometimes be overwhelming. Humanity’s general desire for barbaric realism goes all the way back to the gladiatorial arenas of Ancient Rome, and yet, even this far into so-called civilization, mistakes can still be made.

There have been countless movie mishaps over the years, from the injured stuntman falsely rumored to have lost his life during the chariot race in Ben-Hur, to the tragic deaths of three actors performing a stunt with a helicopter on Twilight Zone: The Movie, two of whom were children. Of course, health and safety organizations have clamped down considerably since then, but there are some films that still somehow manage to slip through the cracks. This list focuses less on single-case incidents of injury, and more on films that were specifically known to facilitate dangerous production environments, but surfaced as great cinematic works, nonetheless.

10. Roar (1981)

Judging by pure visible danger alone, no film tops Roar in sheer idiotic audacity. This one-of-a-kind glorified home-video isn’t by any means a great narrative feat, but for what it lacks in story it more than makes up for in riveting exhibitionism. Directed, produced, written by and starring Noel Marshall, as well as his two sons, his then wife Tippi Hedren, and her daughter Melanie Griffith, Roar claws its way into the beating heart of morbid intrigue, a film which reportedly featured over one-hundred and fifty animals, most of them being big cats.

Over seventy separate on-set injuries were recorded, many of which can be seen in the finished film. It’s near-impossible to categorize a film this unique, but primarily it falls into the realm of exploitation, as so little of it conforms to orthodox storytelling. Amongst the more severe injuries was that of cinematographer Jan De Bont, who was quite literally scalped by a lion and barely survived the grueling attack. Melanie Griffith was also mauled, receiving serious facial lacerations and even concerns from doctors that she might lose an eye.

These two injuries alone amounted to nearly two-hundred stitches, and that’s not even counting the other attacks. Although Roar seems to suggest a do-good message of conservationism and animal welfare, it stands, over time, as an example of what not to do in the film industry, and to let nature be nature without human intervention. This, in essence, is why it remains so important. Not to mention the music is a treat. If you thought Tiger King was nerve-wracking, try this one out for size.

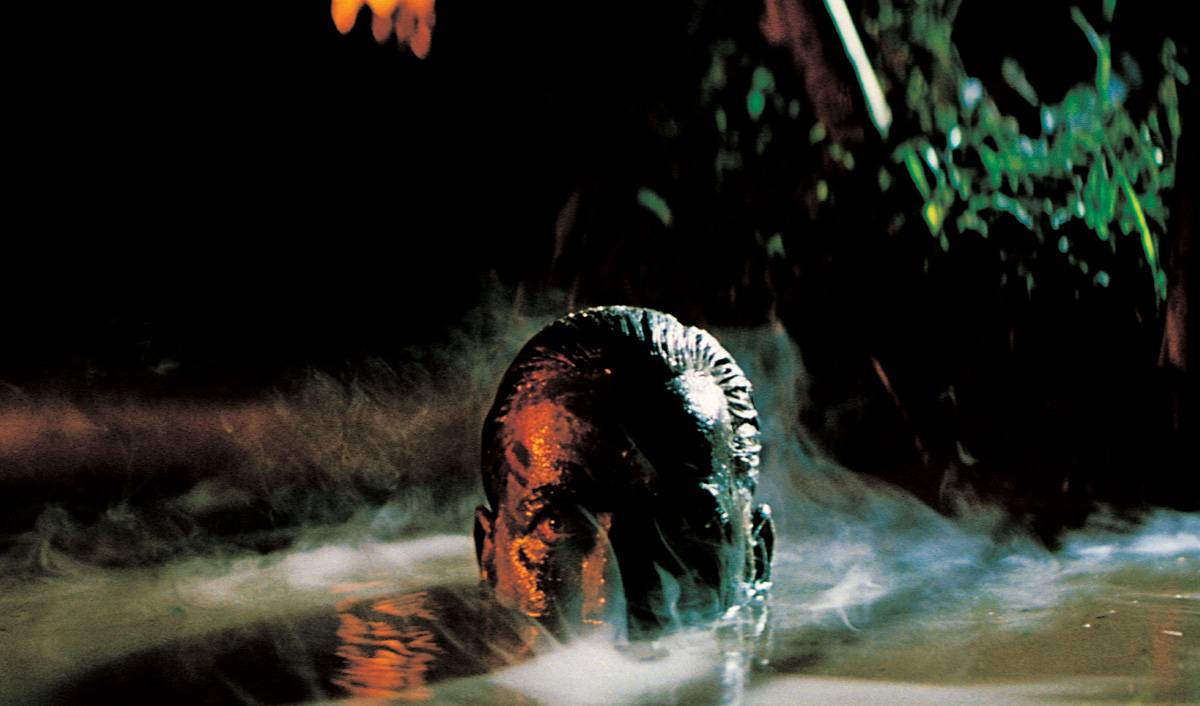

9. Cannibal Holocaust (1980)

Another controversial exploitation classic, Cannibal Holocaust has grown in cult status over the years, never ceasing to haunt every new generation of cinephiles. In many ways, this is the definitive bad stain of stigma on the industry, largely due to the inhumane treatment of animals, most of which can be seen in the movie. To make matters worse, director Ruggero Deodato’s shooting methods were supposedly verging on sadistic, asking the cast to mutilate and kill the animals themselves, as well as screaming at one actress when she felt uncomfortable performing a nude scene.

This evokes an age-old debate: can we judge the film in an artistic capacity despite the immorality of its origin? Shot almost entirely on-location in the Amazon, Deodato essentially had free-reign here, a situation which perpetuated a work environment that was subject to all manners of abuse. Perhaps the most concerning scene of the film sees the lead actors burning down wooden huts with South American locals standing inside them. These native tribes received minimal pay, and some reports state that Deodato asked them to stand amidst the raging flames for an inordinate amount of time. In the face of all this, the film still manages to hang on to its artistic merit.

Sergio Leone once quoted Cannibal Holocaust as a ‘masterpiece of photographic realism’, and as conflicting as it may be to admit, he was right. This film so convincingly emulates violence that Deodato was actually arrested on its release, and the years have taken nothing away from it. Both the figurehead for the term ‘video-nasty’ and the first ever foray into found-footage filmmaking, Deodato’s sadistic work prevails, made all the better by Riz Ortolani’s giallo-inflected music.

8. Candyman (1992)

On the subject of giallo, many new-wave filmmakers rehashed the blood-and-guts mayhem first coined by Mario Bava, most notably Brian De Palma, but it was English director Bernard Rose who created perhaps the most unique meditation on the genre. Candyman is just brimming with ideas, from the opening steady-cam helicopter shot, to the complex political commentary on subjugation and racial divide in America.

This film depends so much on the universally understood fear of bees, featuring one scene in which Tony Todd had an entire swarm placed inside his mouth. This, understandably, made everyone nervous, but it was Todd who ultimately benefitted. A compensational sum of a thousand dollars was written into his contract for each sting, a clause that’s long been recognized as one of the strangest contractual obligations ever penned. By the end of filming, Todd had been stung a total of twenty-three times, bagging a hefty paycheck for his minor injuries.

Unfortunately for the cast and crew, that’s not even the half of it. A large portion of this cult-horror was shot on Chicago’s now demolished Cabrini-Green Housing Projects, an address that was notoriously publicized for violent crime. The producers even secured a deal with the leading gang-members of the area, signing a contract that stipulated if the productions team’s safety could be ensured, the local gangs would appear in the film as extras. Even after this agreement was made, a sniper fired a bullet into the back of a production van on the final day of filming. Miraculously, nobody was injured.

7. Medium Cool (1969)

Master cinematographer Haskell Wexler, well known for his work on The Conversation, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Faces, turned his attention towards directing in this overlooked quasi-documentary, marching his cast and crew into what was essentially an all-out, rampaging Civil War.

Incorporating the Chicago civil rights riots of 68’ into the narrative, Wexler had the actors wade through crowds of armed police and violent protesters, weaving his story through the chaos. These riots, sparked in part by the assassination of Martin Luther King, were among some of the most devastating in American history. For a sense of scale, more than two days of protests left eleven Chicago citizens dead, forty-eight wounded by police gunfire, ninety policemen injured, and an estimated 2,150 people arrested.

With this historical event contained within Wexler’s fictitious story, Medium Cool stands out as an unconventional examination of political uproar, a young Robert Forster giving a mesmerizing performance at the center of it. It’s an accomplishment of unbridled dedication from both cast and crew alike. Many instances of police brutality are caught on film during the riot sequence, and at one point the camera-crew are even teargassed. All in all, this is an unmissable, albeit high-risk, paradigm of late-60s cinema.

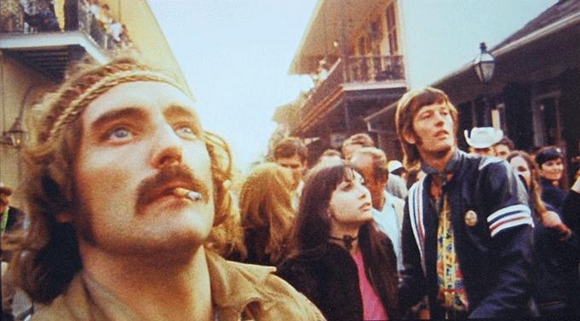

6. Easy Rider (1969)

Maybe the ultimate celluloid example of late-60s counterculture, Easy Rider has long been applauded for its revolutionary dive into independent filmmaking, but the worryingly lawless nature of the shoot can sometimes be underestimated. Under Dennis Hopper’s intoxicated direction, the film maps the journey of three lovable hippies smuggling cocaine from Mexico to Los Angeles, played by Hopper himself, Peter Fonda, and Jack Nicholson.

Considering the political turmoil in America at the time, making this rebellious film was no safe task to be burdened with. Many inhabitants of the states the cast and crew travelled through were relentlessly hostile, not taking kindly to laidback hippies tearing through their terrain on loud Harley-Davidsons. To make matters worse, the three leads consumed a considerable amount of drink and drugs on the road, and on one occasion Hopper was even jumped when entering a bar.

This hostility is best exemplified during the scene in which the three actors enter a café in an attempt to pick up some women, all to be met by a slew of homophobic vitriol from the men sitting inside, one of which was a local police officer. Apparently, these men were non-actors, and when the crew heard them badmouthing the production, or more specifically, the trio’s long, shaggy haircuts, they were asked if they wouldn’t mind keeping up with the remarks on film.