6. Smooth Talk (1985) / Lady Bird (2017)

From a lonely man finding himself to a young girl discovering who she’s about to become, these next two films brilliantly depict a young woman’s coming of age amidst of a delusion of maturity.

For Lady Bird, it’s Christine’s (Saoirse Ronan) inability to accept her youth, leading to friction with her mother Marion (Laurie Metcalf) as she demands to be taken more seriously before the big life-altering move to college. Director Greta Gerwig not only understands and starkly portrays these frustrations, but takes time to depict their genesis, leading to truly emotional and relatable dialogue. However, while director Joyce Chopra succeeds at this with her 1985 gem Smooth Talk, the depiction of these frustrations is taken to a whole new, unexpected level.

Following Connie Wyatt (Laura Dern, in a great pre Blue Velvet performance), a 15 year old schoolgirl growing up in rural America, the audience truly feel her aching as she longs to experience a life away from the pressures of her teen years and to be taken seriously, by both her parents and strangers. What follows is her taking it upon herself to be thrust into experiences far beyond her age, landing her in dark trouble with an overly aggressive onlooker. Chopra brilliantly translates Connie’s teenage anxieties into visceral fear, as the final act of the film subtly and cleverly takes on elements of a horror film.

However, Smooth Talk undoubtedly exists within the same hazy minutiae as Lady Bird. The reasons for wanting to grow out of the hometown are abundantly clear in both, being surrounded by a sleepy community with nothing for anyone younger than 50 to engage with. It’s this diving board that set both central characters into motion in incredibly relatable ways, with inventive scenes in both films of them acting out beyond their years. Dern’s central performance draws the audience in as she steps into the unknown on her own behest, frequenting dive bars and conversing with older men, convinced it will make her become who she is meant to be. This so devastatingly leads to conflict with her mother Katherine (Mary Kay Place) that any and all emotion is totally invested in the characters come the shocking and horrific ending.

Lady Bird perfectly compliments this with the indisputable fact that maturity can not be forced; both Christine and Connie have no control over who they will be in the future, and it won’t come any quicker by acting out. Their mothers lived through it, making their arguing all the more emotional.

While Lady Bird doesn’t get as dark as Joyce Chopra’s coming of age tale, it presents the audience with the same key sentiment.

7. To Die For (1995) / Nightcrawler (2014)

The evils of the media, particularly the seemingly outdated avenue of broadcast news, have long been exposed through film. After a quiet boom during the 1970’s with the likes of The China Syndrome and Network becoming staples of the genre, the exposition of journalistic injustice has continually griped audiences through the decades. And, when Dan Gilroy unleashed his Jake Gyllenhaal lead thriller back in 2014, it was clear the cinema goer’s fascination with a despicable character’s willingness to catch the big story at the cost of human life was far from gone. However, there was at least one overlooked film, released nearly two decades prior, that undoubtedly perpetuated this genre into continued success.

Director Gus Van Sant delivered his similarly star studded thriller to rave reviews at the 48th Cannes film festival, but little notoriety has followed. Starring Nicole Kidman as Suzanne Stone, a hard working, fame obsessed upstart in the television industry, Van Sant’s film is an excellent example of how to effectively build sensationalised dread through film, as the audience is slowly yet careful fed clues as to just how far her delusion with the spotlight goes, and who’s trust she regularly betrays for her fifteen minutes of fame, leading to deadly consequences through a gripping, black comedy lens.

To Die For could almost be considered Nightcrawler’s older, more experienced sister. Gyllenhaal’s Lou Bloom employs just as dastardly and seemingly insane tactics to work his way up the ranks of the newsroom, no doubt inspired by the wicked games Suzanne laid on her subordinates, which actually include a young Joaquin Phoenix as teen softie Jimmy, who is roped into a murder case of her design to gain fame. This so closely echo’s Bloom’s contraction and subsequent weaponisation of his friend Rick’s (Riz Ahmed) trust, that Stone’s story deserves just as much recognition as Bloom’s, with it’s slightly more satirical edge and crucial proverbial winks at the camera.

Both feature great performances and an indulgently cool yet frightening sense of heightened reality, but Van Sant’s To Die For pulls this off with such flare and knowingness that it strikes the perfect balance between insanity and reality, which Gilroy’s feature falls just short of at times.

8. Medium Cool (1969) / The Trail Of The Chicago 7 (2020)

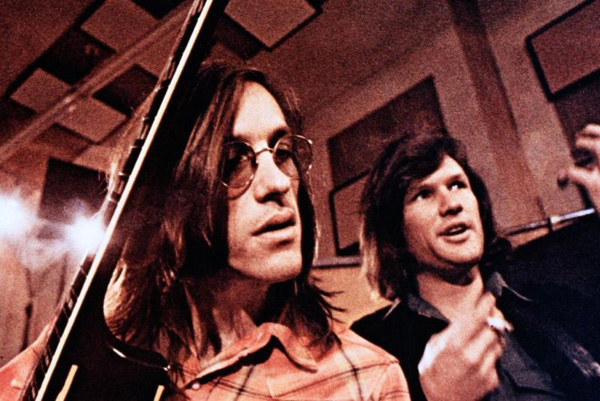

Haskell Wexler’s snapshot of late 1960’s cultural and political eruption is, unsurprisingly and sadly, just as relevant as it was back then today. A fascinatingly styled part documentary part fiction film that actually features real footage from the DNC Chicago riots of Summer ’68, it makes for a fascinating companion piece for Sorskin’s period drama concerning the same subject, half a century on.

Featuring now legendary cult actor Robert Forster in an early lead role as John Cassellis, a news cameraman who uncovers a conspiracy that his workplace is selling information to the FBI, Wexler’s film fascinatingly props up the fictional elements of the plot with real footage of political upheaval and riots, notably the August 1968 DNC protest. Once Forster’s character guides the audience through the second act, the film becomes increasingly and undeniably real. It makes for one of the most impactful stories ever put to modern American film, drawing the audience in with a believable yet fictional plot that subsequently becomes undeniably and horrifyingly real, just when it starts to seem stranger than fiction.

It makes for a perfect mirror image to Aaron Sorskin’s latest, especially as that film focuses on the aftermath of the riots that are actually seen, first hand and documented, in Medium Cool. While The Trail of The Chicago 7 does, of course, benefit from being made fifty years after the fact, with years of commentary and research to inform an engaging story of the proceeding court trail, the fact the film looks and feels incredibly close to it’s past counterpart is a great testament to Sorskin and Co. The two films almost work as prequel and sequel to one another, and in a year that has seen much similar political upheaval, Medium Cool makes for a relevant cultural touchstone today too.

It is a great mystery as to why, even after the release of the new period drama, that Wexler’s subversive classic has not garnered much fervour. It’s an absolutely vital piece of American cinema that worked to shake up conservative society to nearly the same degree that it would be later be in the same year with Easy Rider, brandishing the ugly and hidden side of American that Hollywood refused to admit up to that point. If anything, it provides invaluable context for Sorskin’s epic, delivered in an unsettling and totally gripping manner.

9. Le Samouraï (1967) / Drive (2011)

Jean-Pierre Melville’s character portrait of an emotionally absent, ruthless, yet heroic killer is perfectly summed up by it’s title. Though devoid of any actual Samurai, Melville carefully fashions the characteristics of one into central character Jef Costello (Alain Delon), with his surroundings swapped for mid century Paris as opposed to rural Japan. However, the above description also fits the character of Ryan Gosling’s Driver to a tee.

In Drive, the Driver is not only defined by loneliness, he knows nothing but. It’s a classic character archetype that director Nicholas Winding-Refn crafts brilliantly, in a story of crime, forbidden love and revelation. Despite his violent tendencies, the Driver is rooted for by the audience as they slowly learn that he does what he does simply because he is good at it, and when love interest Irene (Carey Mulligan) is introduced, it’s totally unclear how he will react, as he, unlike usual leading characters, hasn’t been depicted with emotions.

But what brings both Drive and Le Samuraï together at their core is not just the similar stories they share, their lead’s ambivalence to the violence they commit, nor their shared slick demeanours; it’s that these two lead characters not only bypass their emotions, but don’t realise they have them until, devastatingly, it’s too late.

The role Irene fills in the Driver’s life is filled by two women in Jef Costello’s; Jane (played by Delon’s actual wife Nathalie), a prostitute that aids in his alibis, and Valérie (Cathy Roiser), a witness that spares him from persecution from a crime she sees him commit, and becomes integral to the Costello’s life in the film’s climax. But where this difference circles back to Drive is, that, ironically, Costello’s initial love interest only amplifies his lack of emotion, with her profession being one specifically devoid of it. This juxtaposition layers Costello in similar ways to Irene bringing out layers in the Driver, and asks both characters the crucial question; do they need companionship, or love in their life?

Melville set a precedent for modern crime cinema that is universally unrivalled, yet remains one of the lesser known names of the French New-Wave movement. His 1967 masterpiece carries the same trappings, style, action and pace as a modern thriller, demonstrating just how many lightyears ahead of it’s time it was.

10. Cisco Pike (1971) / Inherent Vice (2014)

Drugs, hippies, and rock and roll. Though those words would perfectly describe most any American counterculture film made between 1968-1971, the likes of Beyond The Valley Of The Dolls or The Trip tend to spring to mind first for their fun atmospheres and psychedelic experimentations. But while the above also applies to Cisco Pike, it’s almost worlds apart from the likes of those aforementioned classics.

This forgotten 1971 flick was dismissed at the time of it’s release, being quickly accused of jumping on the Easy Rider bandwagon to cash in on the growing trend of drug centric movies. Yet, with a plot that revolves around the titular washed up musician (with Kris Kristofferson delivering a great, semi-auto biographical performance here) being roped into a huge marijuana deal by slimy cop Leo Holland (Gene Hackman), there is really only one similarity to that particular hippie film. What makes Cisco Pike so special and akin to Inherent Vice is it’s depiction of the counterculture movement in L.A. at the time. Rather than glamorise it as so many films did, which is a notion the current collectively selective memory of the era consists of now, director Bill L. Norton choses to show the dour side of this life. Perfectly pitched by Kristofferson’s own music, the film is an engaging, cool and oftentimes devastating look at the hippie hangover.

And that is what Inherent Vice is really about. Central character Doc Sportello, a lovable and perpetually stoned P.I. caught in a web of conspiracy in an effort to find his ‘Ex-old lady’, exists in a version of L.A. that is violently shaken by the Manson murders, escalating aggression in Vietnam and a disregard for old fashion values, all things that had been attributed to the counterculture movement. The hippie lifestyle at this time was not a good one, and in the coming years, the mainstream, who had tried to snuff them out over the previous decade, would steal their sentiment and style before leaving the movement to die.

What makes Cisco Pike so fascinating is that is was made at the time Inherent Vice is set, and both so effectively display a rare insight into the era. Also, seeing Pike wear almost identical outfits to Sportello and both lead characters having a love/hate relationship with a hippie hating cop fuelled by amazing performances can’t help hint that, although not cited, Anderson must have sneakily seen Norton’s film at least once.

Although some films on this list have been noted countless times as major influences on not just their modern counterparts, but the wider genre they’re housed in, hopefully, this has shed some light on the seldom seen cinema, that would undoubtedly find a contemporary audience thanks to the similarly they share with the listed favourites.

In some cases, it is a totally mystery as to why these films are indeed seldom seen. From Who Is Harry Kellerman And Why Is he Saying Those Terrible Things About Me? holding the record for the film with the longest title to carry an Academy Award nomination, to Le Samuraï not only being a major influence on filmmakers such as Jim Jarmusch and John Woo but even pop star Madonna for her song Beautiful Killer, they have simply slipped through the cracks of the cultural memory. Yet they absolutely demand to be seen, not just by film buffs, but by anyone who revels in great storytelling, cultural exploration and a unique perspective.