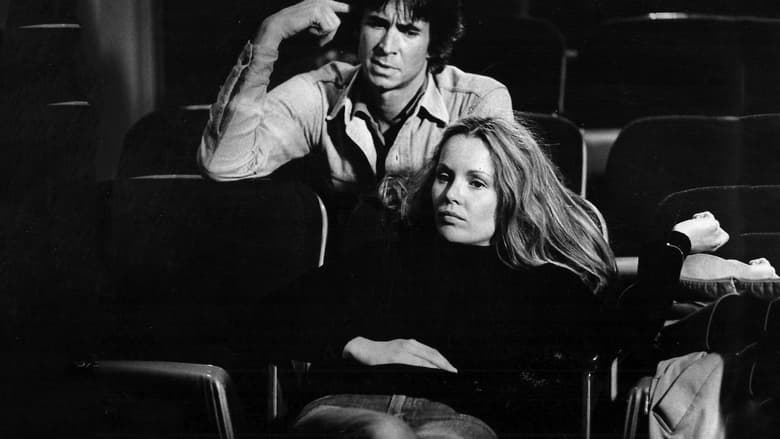

6. Play It As It Lays (1972)

Culture writer and author Joan Didion had her finger firmly on the pulse of Hollywood in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Her 1970 novel, Play It As It Lays is stark proof of that, as it charts the dark underbelly of the film industry through an almost aimless wonder. Directed by Frank Perry, this film version is a great inspiration on Tarantino’s latest, being an incredible snapshot of Hollywood in the same era it’s set.

Maria Wyeth (Tuesday Weld), a once successful actress now institutionalised for depression, looks back on her life in Hollywood. Through her flashbacks, she recounts driving through L.A. in her sports car, her tenuous marriage to director Carter Lang (Adam Roarke), her friendship with B.Z. Mendenhall (Anthony Perkins) and increasingly numbing extramarital affairs with Hollywood professionals, on and off screen.

There remains a rumour that Didion wanted Sam Peckinpah, director of blood thirsty westerns such as The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, to helm the film version of her novel, and one can only assume that if that were the case, it would’ve come out near identical to Tarantino’s OUATIH, a similarly blood drenched Hollywood tale. Nonetheless, Perry’s final version of the film help’s build Tarantino’s world, with clear connections between Wyeth’s point of view and Cliff Booth’s, placing the audience in the car with both in order to observe the industry at the time from the passenger seat.

Didion herself actually spent a lot of time with the Manson cut followers, most notably Linda Kasabian. Despite not alluding to the Tate/La Bianca murders here, it’s proof that she more than most understands the dark side to the industry, and just as OUATIH shows (albeit in a far more pulpy fashion), the blurred line between pop culture and real life during this transitional era could easily bread a dark, usually unseen side in those involved, and those that want nothing but to be.

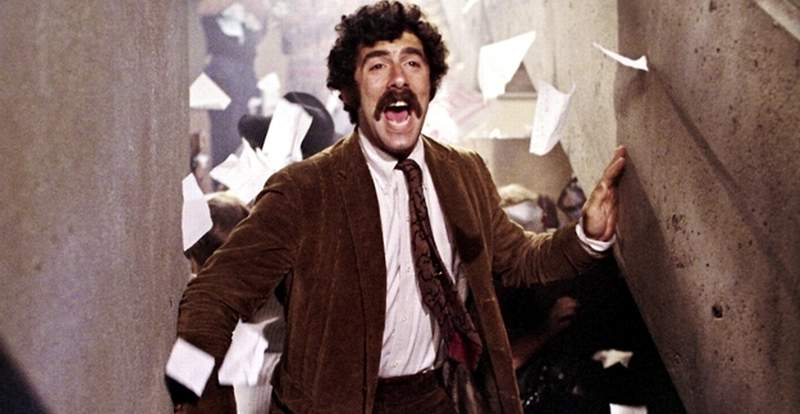

7. Getting Straight (1970)

As featured on Tarantino’s ‘Swinging Sixties’ watch list in preparation for OUATIH, this first entry by genre filmmaker Richard Rush is a great starting point for understanding the world that surrounds Rick, Cliff and Sharon, outside of the film industry and into the real world (or as real as it can be).

In a similar way to Rick Dalton realising how out of step he is in the changing tide of the late 60’s, the film follows Harry Bailey (Elliot Gould), a once student radical who is back at university to study for his Masters degree. Despite his past, he stays more in line with the faculty this time round, much to the chagrin of his girlfriend Jan (Candice Bergen). As protests and turmoil further engulf the school, Harry has some big choices to make.

Though there were a number of films of this ilk being released in quick succession at this time (Zabriskie Point, R.P.M and Medium Cool to name a few), this romp stands as one of the most fun of the bunch. Gould’s performance here is heaps of fun, striking a balance between the serious tone of what the students want justice for and the frantic nature of trying to find oneself in the midst of the chaos.

And it’s exactly that chaos that informs the world around OUATIH’s fictional and non-fictional characters, as Tate teeters on the edge of falling inline with the youth (expanded upon in the novelisation, the scene in which she picks up a hippie hitchhiker reveals her true good nature and spontaneity), Cliff tries to stay out of it and Rick despises them. Interestingly, Getting Straight mirrors similar character tensions in OUATIH, highlighting just how drastically culture was changing at the end of the 1960’s and how to fit in. Though Tarantino’s film largely stays out of political commentary, a line dropped by Manson follower ‘Pussycat’ about the Vietnam death toll evokes the wider conversation of the time that Elliot Gould and co do such a great job of demonstrating here. It just further helps to plant Rick and Cliff into the real world at the time.

8. For A Few Dollars More (1965)

“I got to do f——-g Italian goddamn movies! That’s the f——-g problem”. For the all American Cowboy star Rick Dalton, the very notion of having to leave his native land to continue his profession would be nothing short of an insult, resulting in his above qoute. However, at that time in Hollywood, European westerns were becoming not only a viable source of income, but successful next steps for actors who were starting to slip out of the Hollywood limelight, with this next film being a key example of that.

The second in Sergio Leone’s seminal Dollars trilogy, the film follows Clint Eastwood’s endlessly cool ‘Man with No Name’, as he journeys to El Paso. There, he forms an unlikely partnership former Army colonel Douglas Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef) in effort to stop recently escaped convict and bank robber El Indio (Gian Maria Volonté). As he and his gang ruthlessly ravage the small town, violence ensues and loyalty is put to the test.

The Dollars trilogy have long been regarded as some of the best films ever created not only within the Spaghetti Western sub genre, but the western genre as a whole. However, at the time of their release, at least to Hollywood types, they were largely looked down upon as the cheaper alternative to the classic American western (which was starting to become obsolete by the time of the late 60’s anyway) with no name actors. Much like Rick Dalton, Clint Eastwood spent most of the late 50’s and mid 60’s as the hero of a western T.V. show (playing none other than Rawhide’s Rowdy Yates) and periodically guest starring on similar small screen shows, with neither managing to break the big screen.

Though Rick sees the suggestion of moving to Rome to join the Spaghetti Western fun as “the fate worse than death”, his resulting decision to do so saw his garner success similar to the level Eastwood did in real life. This second film in the trilogy demonstrates a moment when they began to be taken more seriously, with a grander plot and bigger spectate than it’s predecessor, Fistful Of Dollars. Additionally, the violence featured being far more daring than anything an American western would dare to feature signalled the changing cinematic tide that would inevitably catch up with Hollywood, as the Dollars trilogy increased in popularity over the decade.

9. Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969)

Speaking of Hollywood’s changing tide, this next film (another personally recommended by Tarantino ahead of OUATIH’s release), went a long way to break down social and cultural taboos with its ingenious melding of old Hollywood and the burgeoning new. In surrounding Tarantino’s fictional and non-fictional characters in 1969, it makes for very interesting framework about their own beliefs.

After returning from a couples retreat, socialites Bob (Robert Culp) and Carol (Natalie Wood) decide to opt for total openness and acceptance in their marriage. After an extramarital affair each, their close friends, Ted (Elliot Gould) and Alice (Dyan Cannon), are deeply shocked by the news and subsequent nonchalant attitude toward it, but soon decide to attempt to adapt to the same mindset.

Director Paul Mazursky so very cleverly yet simply frames the story with the two couples that it could almost be seen as allegorical; Ted and Alice represent the old Hollywood and Bob and Carol represent the new. Though they’re counterparts, the changing social times are drastic enough for a major rift to be caused. In fact, casting old Hollywood staple Natalie Wood as Carol ingenuously hints to this.

Margot Robbie’s free flowing portray of Sharon Tate evokes the spirit of the four main characters here (especially Bob and Carol), and while Rick’s personalities doesn’t particularly match the outrage and awkwardness of Ted and Alice, he’s almost their counterpart in the sense that they’re all wealthy L.A. socialites (to a degree) that desperately want to find a way of fitting in while staying the way they are.

Additionally, this milieu of contrasting beliefs and morals lead to such inspiring set design and cinematography for OUATIH, providing great guidance for the crew to find a balance between hip and old fashioned. From Rick’s clothes and house to the groovy extras lining the streets of L.A., Mazursky’s film seeps through as a reminder that not all of the hip folk at the time were hippies; they were just trying to figure themselves out in a new context.

10. The Stunt Man (1980)

This final entry, another Richard Rush film, is somewhat of an outlier in many respects (being made well after Tarantino’s latest is set), yet is incredibly pertinent to OUATIH in many other aspects. As films about filmmaking usually do, this dark action comedy works to blur the lines between fiction and non fiction, and makes a crucial statement that Tarantino also does; that the film industry is essential American folklore.

In an attempt to evade capture after becoming a fugitive, Cameron (Steve Railsback, who, eerily, famous portrayed Charles Manson in a 1973 television movie), stows away within a local film production crew, masquerading as a stunt double. Here he meets the eccentric and almost omnipresent film director Eli Cross (Peter O’Toole), who immediately takes a liking to the criminal. Slowly, Cameron becomes unrecognisable, yet is constantly skeptical about Eli’s increasing interest in him.

Despite the obvious link to the smaller context of OUATIH in terms of being a film about the film industry and the physical making of the medium, what this film has really imported on the latter is the fact that it treats the entertainment industry, at least in America, as nothing short of religion. Eli Cross intentionally appears as somewhat of a omnipotent God, either by descending from the skies in his directors crane or wearing all white. However, aside from reading that as a statement on ego, it can be seen as an interpretation of the industry as an all encompassing religion, with him, in this context (passing judgement on Cameron and granting him a new life), as their leader.

In OUATIH, the industry is essentially Rick’s religion. It engulfs his entire existence, and, like folklore, he can only look back, longing for a simpler time. Considering the high esteem he holds that time in (and some of his contemporaries), just how the industry is depicted in The Stunt Man, there’s a clear parallel.