5. The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980-1994)

A handful of critics derided South African director Jamie Uly’s “TGMBC” series as silly or patronizing (or simply for being from Apartheid South Africa which wasn’t really its fault). But what made it special and more respectful than detractors gave credit for was not its actual stories but its degree of authenticity and ingenuity within them: using real village, bush and Kalahari desert locales, real villagers and tribes, and most boldly of all casting a real Bushman (properly known as Saan) as the series’ protagonist.

A gamble though it was, it turned out to be an incredibly successful one. The first entry was an unexpected massive international hit at a time when very few non-American/British movies were, particularly in the US and most of all Japan, where it broke box office records for foreign films and films altogether respectively, grossing more than $100,000,000.

And from that we got arguably the most unlikely film superstar in history: Nǃxau ǂToma. That is not a typo. He was a Namibian Saan who mainly spoke !Kung (the “!” in such languages indicate tongue “clicking” sounds) and Otjiherero, was illiterate, didn’t have an ID, birth certificate or record of his age, and had never even been in a city or town before discovery in the Kalahari by Ulys.

But even when he lived most of the last two decades of his life through whirlwind international celebrity status, and even when he loved encountering “exotic” people and customs in Europe and Asia (especially sake), he chose to finish his life right back where he started as a hunter-gatherer, falling ill when hunting guinea fowl. Thus sadly, he was naturally not understanding of his literal worth, as he was paid $2000 from the initial run of “TGMBC” (and wasn’t sure even how to use that) — literally less than 1/50000th of its earnings.

At its best, the series cleverly played with perceptions of what it means to be “civilized” and the general awkwardness of man’s struggles to live in new kinds of environments (not just N!Xau when he encounters cities and city folk, but city folk when they find themselves in his territory too). While every installment had characters with more screen and speaking time than N!Xau, everyone knew he was its real star as only he appeared in them all and every story revolved around his endearing warmth and naturalness in every sense.

The 2nd entry plays more like a children’s story in cranking up the animal presence and cartoon hijinks (from a real civil war, funny enough). But just when it was thought things couldn’t get any weirder for a Bushman celebrity, after the first two regular entries there would be three semi-official sequels (with Ulys consulting) from Hong Kong: 1991’s “Crazy Safari” (the most gleefully weird of them all, where N!Xau’s village is “invaded” by a hopping vampire), 93’s “Crazy Hong Kong” (where he wanders around the city) and 94’s “The Gods Must Be Funny in China” (where he joins a Beijing marathon, co-starring Kent Cheng).

4. Ip Man (2008-2019)

When Donnie Yen first signed on to play the fairly modest Wing Chun master known most for being a teacher of Bruce Lee, chances are neither he nor director Wilson Yip could’ve imagined him becoming a national icon and the series becoming a multi-pronged commercial juggernaut (with just as many fans and as much commercial power as many famous Western franchises now) as they did.

How did the series get there? By cleverly molding itself to emerge as the pan-Chinese world’s first modern crowd-pleasing blockbuster franchise that made a fighter/sportsman really just famous in his field into a larger-than-life national hero — very much their Rocky Marciano [Balboa], so to speak. But while having more than enough martial arts action to please any fans of the genre (thanks to ever-brisk choreography from Sammo Hung for the first half and Yuen Woo-ping for the second), the series is not all spectacle and bombast.

Even if they’re clearly not even trying to be straight, unembellished biopics, the series does put decent effort into recreating the historical atmosphere of the times and places from the family’s birthplace in Foshan, Guangdong to colonial Hong Kong, major figures in his life including Lee, and quoting or reflecting the philosophies of the Grandmaster as Ip was called.

So every entry would have him facing insurmountable odds, with his personal conflicts that he gets dragged into serving as a template for China’s own such massive struggles in its modern history: against invading Japanese in direct competition with their karate in the 2008 original; against a British boxer supported by corrupt and arrogant colonial officials in 2010’s “Ip Man 2”; against a fearsome American real estate broker/brawler making deals with triads in 2015’s “Ip Man 3” (none other than Mike Tyson, surprisingly in by far the most serious and physical role of his movie/TV career as he directly spars with Yen); then alluding to modern world issues when facing off against White/American supremacists on 2019’s finale “Ip Man 4”.

He also fights various local rival martial arts schools and criminal organizations in between it all, giving Yen opportunities to spar with some of China and Asia’s finest martial arts stars across generations like Sammo Hung and Max Zhang. But the finest on that front was the 2018 spin-off “Ip Man Legacy” without Yen but with a truly international martial arts cast including Zhang, Michelle Yeoh, Tony Jaa and Dave Bautista. While the series showed a little more difficulty with staying fresh every new entry, it stayed highly entertaining all the way with moxie one can’t help but respect.

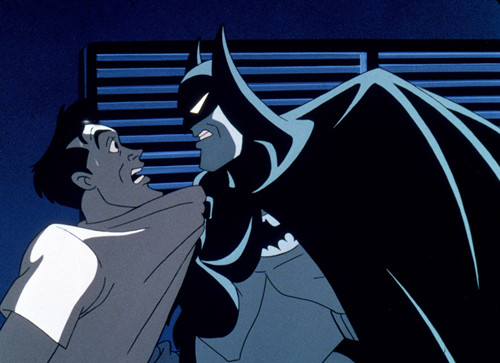

3. Batman (1st animated movie series) (1993-2003)

As easy as it is to forget (or for the younger to not be aware of at all) in this day and age completely flooded with big-budget, big-name superhero productions, there was a time not that long ago at all when live-action superhero movies were sparse, quite consistently underwhelming and more than a few times outright terrible. And at that time for those not harboring biases against it, animation was easily a better choice overall for superhero entertainment than live-action movies.

That even applies to one of the two most popular superhero movie franchises before the 21st century: Batman. A few years after Tim Burton’s game-changing 1989 Batman movie, there would be a spin-off syndicated show called “Batman: the Animated Series” that’s generally regarded as one of the very best of its kind and that appealed to teens and adults like very few other non-prime time cartoons of the era (but is now best known now for having created the character Harley Quinn and the continuing legacy of Mark Hamill as the definitive voice actor for the Joker). Spinning off from that series would be four different movies: “Batman: Mask of the Phantasm” (1993), “The Batman/Superman Movie: World’s Finest” (1997), “Batman & Mr. Freeze: Subzero” (1998), and “Mystery of the Batwoman” (2003). (One can count five if also including the 2000 futuristic spin-off “Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker”).

Truth be told, “Mask of the Phantasm” — tracing Batman and Joker’s origins alongside introducing the titular antihero still used today — was not only more true to the comics with its dark and gritty (but not Burton baroque) aesthetic and story than any other screen Batman of the 20th century, but is hands-down better than any of the other 1990s Batman movies. The subsequent three in the series were more kid-friendly in their style but not childish.

The Superman crossover was particularly well-written and conceived in bringing the characters’ worlds together (meaning quite the opposite of Zack Snyder’s mess of a story and premise in “Batman vs Superman”), and “Batwoman’s” Bane was actually more faithful and convincing than Christopher Nolan and Tom Hardy’s bizarre English Gentleman Bane of “The Dark Knight Rises” — let alone the abomination of “Batman & Robin”. Speaking of which, “SubZero” became a highly unusual and amusing case where an animated video tie-in to a major Hollywood picture ended up wanting to directly dissociate itself from its bigger companion after the latter’s infamous failure, removing all name associations and even putting off its release a whole year to wait until fans removed the bitter taste from their mouths.

2. Whispering Corridors (1998-2009)

1998 is marked as a pivotal year in modern Korean cinema, when the industry finally ceased with decades of almost nonstop severe government censorship and/or neglect. At the nadir the country only produced about a couple dozen movies per year and their own box office was almost completely dominated by Hollywood. That’s hard to imagine for an industry that had a meteoric rise in popularity internationally over the past two decades with separate international “Korean Waves” in Asia (spearheaded by “My Sassy Girl”), then the West (by “Oldboy”), then globally (with “Parasite”).

But none of that could’ve occurred as it did if not for the domestic breakthrough to take back their own industry just a few years earlier, for which a significant part was the “Whispering Corridors” series. They were only really united in their themes and styles rather than their plots: all involved stories about ghostly hauntings in girls’ secondary schools. Stylistically, they were elegantly atmospheric and melancholy.

Nevertheless, there was still always room in the series for some sudden, shocking and sometimes gruesome (and gruesomely creative) death scenes: by window curtain, by light bulb, by cello strings and most often by supernaturally “assisted” suicide. The films served three major functions at once: they were fully capable, entertaining films in themselves; they were very influential in popularizing and setting tropes for the horror genre in Korea then other parts of Asia to a lesser extant; and they provided sharp, timely and provocative statements and reflections on Korean society.

The 1st had nerve-touching undertones about the suffocating nature of Korea’s school system and past dictatorship; the 2nd through the 4th all had tastefully explored lesbian themes (which was groundbreaking for the 2nd and best of them all, 1999’s “Memento Mori”); the 3rd and 4th had graceful performing arts backdrops (ballet and classical song); and all 5 entries — usually intensifying each time — had themes of fragile female friendship, isolation, depression, guilt and suicide.

The later entries would be less bold (as it would also be much harder to push the envelope in a Korea that had rapidly liberalized since the 1st), but that’s offset by how due to past success, they also became more polished (but never ostentatious) in their special effects and production values. Serene and sophisticated yet scary and sanguinary, specific to one nation’s circumstances yet still internationally interpretable, and sharply focused on a very particular demographic (Korean girls’ school girls) yet near universal in its appeal and appeals, there’s simply no other large horror franchise like it.

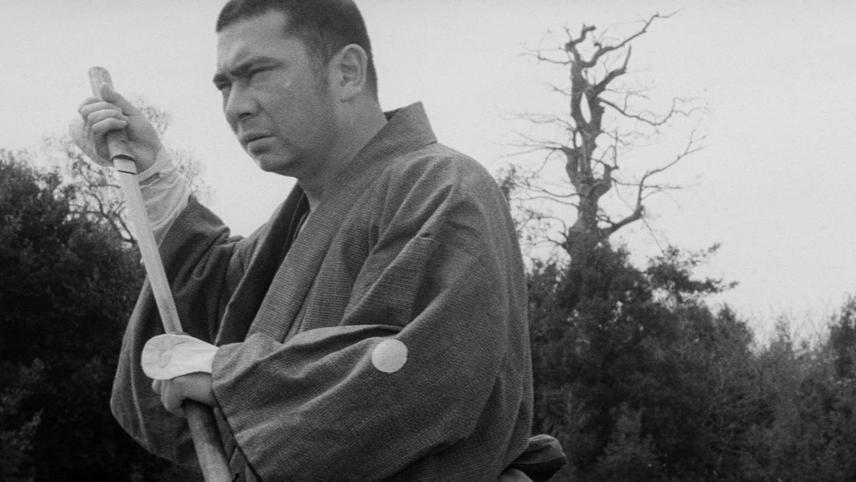

1. Zatoichi (1962-1989, 2001-2010)

While technically a literary character, Zatoichi AKA The Blind Swordsman/Masseur that generations of fans would come to know and love was really the brainchild of actor Shintaro Katsu who developed, fleshed out and ultimately played him for 37 years. It wasn’t just Zatoichi’s super-sharp sentience for lethal efficiency in slicing up anything or anyone who gets in his way or on his bad side with his walking cane/sword, or the gracefully rhythmic violence of the films’ combat that drew followers. Perhaps the most compelling thing about him was his common man’s sensibility far removed from other samurai heroes. Particularly fine entries include the striking “New Tale of Zatoichi” (#3) which poignantly portrays him as a tragic hero, and the incredibly lively and clever “Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold” (#6).

There were also two surprise crossover movies with two more of Asian cinema’s greatest swordsman franchises: 1970’s “Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo” (#20) with Toshiro Mifune reprising his role post-Kurosawa, and an at the time rare cross-country-crossover with Wuxia legend Jimmy Wang Yu’s fellow handicapped warrior in 1971’s “Zatoichi Meets the One-Armed Swordsman” (#22), which even had two versions in the more realistic Japanese samurai genre and the fantastical wuxia style to accommodate each industry’s audience.

Besides the general content and characters themselves, there were many other factors that managed to lend and maintain vitality in what would sound like a tedious franchise (after all, how much can be done with the simple story and concept of a blind swordsman with very little background detailed just liking to wander around and gamble?). One advantage was a rotating litany of much of Japan’s finest talent for period films.

Directors who weren’t big guns like Kurosawa or Kobayashi, but lesser-known ones who often dedicated most of their entire careers to period samurai/ninja/yakuza films contributed, including Kenji Misumi (“Lone Wolf & Cub”), Kazuo Ikehiro (“Shinobi no Mono” and “Sleepy Eyes of Death”), the most famous contributor Kihachi Okamoto (“Sword of Doom”) and Katsu himself for two of the last entries. Major composers like Akira Ifukube (“Godzilla”) and actors like Katsu’s brother Tomisaburo Wakayama (“Lone Wolf & Cub”) also pitched in.

The original series ran for a remarkable 26 entries, with an additional 4-season, 100-episode 70s TV series that started right after the film series (except the belated 1989 final installment), with stories ranging from humorous and upbeat to harrowingly graphic and dark. But even after the original run was clearly finished upon Katsu’s passing, Zatoichi has proven extraordinarily versatile for a series from 1962, making it one of the longest-running in the world just 8 years behind Godzilla and 6 months ahead of James Bond.

It got an irresistibly flashy reboot in 2001 from “Beat” Takeshi Kitano (which caps how they tended to get bloodier and bloodier from #16 onwards), a filmed 2007 stage play from Takashi Miike, a female version of the character in 2008’s neo-spaghetti western-like “Ichi”, and the most recent thus far, a 2010 realist version toning down the quasi-superhuman qualities called “Zatoichi: the Last”.

Throughout the whole franchise, excellent choreography and an appealing protagonist pervaded — though to my knowledge the series never did explain why and how a blind, broke, derelict, generally uncouth compulsive gambler quickly and constantly charmed all kinds of women into ending up in hot springs with him or wanting to marry him. Even if nothing close to a household name outside of Japan (although Hollywood, China and other industries ripped off the character way more than once including in the “Star Wars” franchise), “Zatoichi” has nevertheless proven itself with modest but just as certainly veritably loyal followings all around the world.