In the eyes of many the horror genre is a lower form of cinema, often regarded simply as cheap and easy thrills that exploit the most unsavoury tastes of filmgoing audiences. This can even be seen evidenced in recent years with the proliferation of films labelled as “elevated horror”, such as the work of Ari Aster and Robert Eggers, that seem to be presented as “respectable” films still within the horror genre with larger production values and claims to deeper meanings beneath the surface violence and gore.

However, this does a great disservice to the cheaper, B- movie horror film. Of course, the B-movie horror does have a cultish, dedicated fan base surrounding it that love the genres freedom of expression and appreciate its sometimes rough and shoddy edges. A community that love the now cheesy lines, blatantly fake blood and revel in its uninhibited, but to the larger public it is a variety of film that they would only dare venture to at an adolescent slumber party to then laugh off the next morning. No matter the budget nor the subject matter, when the horror movie is made well it is perhaps the most expressive and malleable of genres for a filmmaker; allowing an expansive range of creative choices to be made in performance, cinematography, editing and mise-en-scene.

Throughout the twentieth century Europe produced a vast array of B-movie horror films that were largely overlooked at the time and forgotten about today. Relaxed censorship laws across the continent were passed in the nineteen-sixties that allowed more sex and violence on screen which filmmakers and producers recognised could attract a fair audience for a feasible price. This resulted in what is often regarded as “Eurotrash” cinema, which also at times overlaps with the infamous cycle of “video nasties” in the seventies and eighties. However, within this there was still creativity and art at play; where effective filmmaking was exhibited and interesting practical and thematic choices were made.

The Giallo is perhaps the most famous of the European horror sub-genres which were a cycle of Italian slasher films, famous for their numerous twists on the traditional slasher form and admired for their savage set-pieces, hyperstylised imagery and scintillating soundtracks. Noted directors of this cycle include horror icons such as Mario Bava (Black Sunday, Black Sabbath) and Dario Argento (Suspiria, Deep Red, Tenebrae). As Italy focussed more closely on the freshly allowed graphic violence, much of the rest of Europe’s horror films were marketed on the basis of sex and nudity made by transcontinental directors such as: the French Jean Rollin and Alain Robbe-Grillet (the same Robbe-Grillet that wrote Last Year in Marienbad and spearheaded the nouveau roman); the Polish Walerian Borowczyk and the Spanish Jess Franco and Jose Ramon Larraz.

1. Spirits of the Dead (Roger Vadim, Louis Malle, Federio Fellini, 1968)

One needs little more reason to visit this unique gem than the list of names involved in its production: Federico Fellini, Louis Malle and Roger Vadim directing Alain Delon, Brigitte Bardot, Jane and Peter Fonda and Terence Stamp in an anthology of three short films based on stories by the Grandfather of Gothic-fiction Edgar Allan Poe.

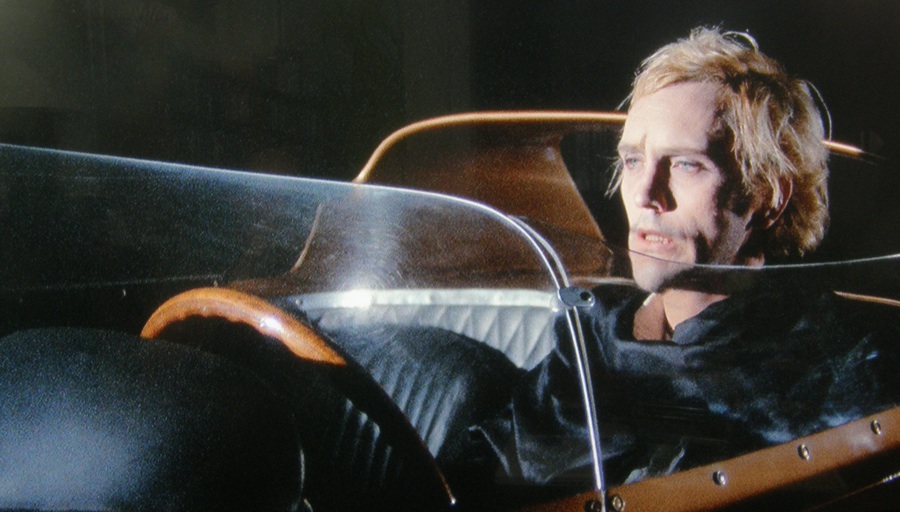

The strongest chapter of this film is undeniably Toby Dammit from Federico Fellini- a filmmaker no one could ever accuse of being “Eurotrash”. Loosely based on Poe’s “Never Bet the Devil your Head”, Toby Dammit stars Terence Stamp as the eponymous lead; a brattish, British movie star who is plagued by visions of a little girl in white that he believes to be the devil. Fellini’s depiction of the girl is particularly disturbing as her ghostly-pale face smiles sinisterly through her hair, piercing through the camera and straight to the spine; reminiscent in manner to what has popularly become associated with Japanese horrors like Ringu and The Grudge. However, Fellini admitted that the origin of the demon girl was a homage to Mario Bava’s Kill, Baby… Kill. Even the poster boy of Italian art cinema had to admire the talents that lay within B-movie horror picture. These visions, along with the troubles of alcohol and stardom, take their toll on the psyche of Dammit as he descends furiously into insanity.

Toby Dammit is disorienting, dazzling and delusive; perhaps unsurprising from the maestro who created the likes of La Dolce Vita and 8 ½ which similarly address the struggle of stardom and fame. Fellini has his finger on the pulse of the youthful, chaotic energy of the times in 1968, possibly predicting the unravelling and demise of the egotistical, excessive stars of the sixties like Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin. Ironically in Spirits of the Dead, Fellini very much presents us with the spirit of the living while also revealing the darkness behind much of the glitz and the glamour of fame.

Although overshadowed by Dammit, Vadim’s Metzengerstein and Malle’s William Wilson are by no means poor efforts. Metzengerstein presents Jane Fonda as a medieval queen who plays with human life at her whim to a degree that Caligula would be proud of. Despite the somewhat lagging narrative, Vadim presents the story in a way that feels similar to Roger Corman’s takes on Poe classics as he depicts an excessive and seductive vision of medieval life with skimpy costumes adorning large performances in even larger castles. It is also worth watching to witness the curious incestual chemistry between Jane and Peter Fonda playing conflicting cousins that flirt with the taboo.

In Louis Malle’s segment Alain Delon stars as William Wilson, a sadistic narcissist who is tormented at different stages of his life by his doppelganger with the same name. Throughout the story, William Wilson #1 enjoys gambling, cheating and torturing women for his pleasure, only to be thwarted at every turn by his double in what can only be a metaphor for his own conscience. This is also worth watching to see archetypal blonde-bombshell Brigitte Bardot turn brunette and go toe to toe with Delon at a game of cards.

2. The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh (Sergio Martino, 1971)

A dark horse of the Giallo genre in the shadow of Argento and Fulci, Sergio Martino produced some of the most accomplished and interesting Italian slashers of the twentieth century. Martino mastered the mix of ambition and madness that many other horror directors of the period struggled to balance, competently conveying the chaos within his film with style and flourish. In the space of just two years Martino directed five of the most noteworthy Giallo’s with Torso, All the Colours of the Dark, Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I have the Key, The Case of the Scorpion’s Tale and The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh.

The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh is a Freudian frenzy of a film in which the icon of Italian horror, Edwige Fenech, stars as Julie Wardh, a masochistic socialite caught between a boring husband, a passionate boyfriend and the cruel goading of an ex-lover. Mrs Wardh is said to be excited and repelled by blood at the same time; much like the horror audience that watches. As numerous murders terrorise the community and Julie receives increasingly threatening letters, she can only suspect that her sadistic ex-lover is behind it all.

Martino controls spectator interest through this intriguing mystery and intense set-pieces. Particularly notable is the killing of one victim in a public garden as she waits at dusk for an agreed meeting with an anonymous tipster. Martino utilises the parks paths and trees to create a tense concern for the woman as he emphasises her isolation and vulnerability in long shots, dwarfing her in the surrounding greenery, and from within the bushes themselves in the point-of-view of the killer. The film eventually builds to a thrilling climax in a rural manor in which a gas leak, an ice cube and a lever handle lock are cleverly used to trap the incapacitated Mrs Wardh.

However, The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh still includes Martino’s trademark madness such as the leap of an assumed dead killer across the room like Michael Myers on springs and so many twists in the final third that you will you become unsure whether the film will ever really end. One can say what they want about Sergio Martino’s films but they are never bland and they are never boring.

3. The Red Queen Kills Seven Times (Emilio Miraglia, 1972)

The plot of The Red Queen Kills Seven Times rests on a century’s old family legend in which every hundred years the Red Queen rises and claims seven new victims. Forever quarrelling sisters Kitty and Evelyn learn about this when they are children but years later, after Kitty believes Evelyn to be dead, is her sinister sister committing multiple murders in the guise of the Red Queen and saving Kitty until last?

Themes of haunting and guilt perturb through this stylish mystery thriller from Emilio Miraglia who had previously directed The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave, seemingly having some sort of a fascination with this name. Miraglia delves into the seedy underbelly of upper-class society as the outwardly well-to-do characters partake in blackmail, drugs and prostitution, examining the dark universal truth of humanity: that people, no matter how much of what they already have, will do whatever they can to get more. The only character that seems to be above suspicion throughout is Barbara Bouchet’s Kitty who drives the film with her incredibly emotive face and wide eyes of pure innocence. Surely, she cannot harbour the dark past that she so believes.

There are some magnificent sequences in The Red Queen Kills Seven Times including an oneiric montage in which the ghost of the Red Queen strokes Kitty’s hair as she sleeps and then tortures her and a wincing death in the vein of Hot Fuzz in which a spike penetrates through the chin of a victim.

4. Who Saw Her Die? (Aldo Lado, 1972)

The opening to Aldo Lado’s Who Saw Her Die? is almost perfect cinema; atmospheric and intriguing filmmaking that immediately captures your attention and draws you in. Lado opens in the 1968 French countryside as a little girl, Nicole, and a nun play in the snow. As Nicole sets off on a sled to be chased by the woman, the camera’s gaze is cloaked by a black veil. Cutting to a long shot of the girl sliding down a hill, a dark, veiled figure approaches her destination from the left of the screen. The creepily considered yet everyday execution of this action, coupled with the anticipation of the intentions of the cloaked figure, grants this image an intangibly eerie quality.

The minute that Nicole has been out of the nun’s sight, she is dead. Once again, we are positioned behind the veil of the killer as the nun approaches and discovers the corpse of the little girl. She looks directly at the camera, the killer, and the image freezes the look of realisation upon the nun’s face in the snow. It is clear that she is next. Cut to the title and the soundtrack of a choir of chanting children, scored by the late, great Ennio Morricone, and you are ready for the next 90 minutes of cinema ahead of you.

While Who Saw Her Die? is able to keep up this momentum for a while, it unfortunately struggles to hold on to the strength all the way to the end and somewhat gets lost in the twists and turns of its own labyrinthine plot. However, it is still a fascinating watch. After the opening, the rest of the action takes place in Venice, making it impossible to not relate to Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now despite it actually being made the year prior to Roeg’s masterpiece. Meanwhile, a lead performance by former Bond, George Lazenby, adds a further layer of interest to this little-known film.

5. The Iron Rose (Jean Rollin, 1973)

Jean Rollin occupied the space somewhere between poetry and pornography, making Gothically gorgeous films fascinated by vampires and the undead. Rollin’s films don’t sit perfectly in any exact genre as their tenderness equals their terror and their subtlety equals their sleaze. Rollin himself categorised himself within the “fantastique”; a subgenre of fantasy where time is non-linear and logic is defied. Prioritising atmosphere and imagery over story, Rollin’s pictures can polarise audiences who expect a conventional, narrative-driven film. Rollin is most famous for his succession of vampire pictures including The Shiver of the Vampires, Requiem for a Vampire and, arguably most of all, Fascination (despite technically not being a vampire film, it does include a cult of blood-drinking women).

However, The Iron Rose is not a vampire picture and instead is a fairly simple story that follows two lovers who become lost in a cemetery overnight. As the nocturnal hours pass, the girl becomes enamoured with the cemetery and begins to identify with the world of the dead over the world of the living. Slow and atmospheric, The Iron Rose is not filled with gore or scares but rather penetrates the psyche of the spectator and creates a calm eeriness as if you were really accompanying the young couple on that dark Autumn night.

In typical fashion, Rollin imbues the film with beautiful imagery that supports the tone of the film and represents his examination of the boundary between life and death. A clown lays flowers at a grave; a visual oxymoron of joy and solemnity. The two lovers embrace in a grave surrounded by skulls; simultaneously juxtaposing and combining the ideas of love and death in a succinct Gothic image. The titular Iron Rose itself representing the theme of immortal beauty and importance after death.

The Iron Rose has the energy of an early childhood memory in which you can no longer remember if it was real or just a dream but either way it had profound effect on your soul.