The use of ultimates can be a dangerous thing. Calling anything or anyone something that generally ends in the suffix est, or some variation thereof, is almost like a call to arms. There will inevitably be someone(s) else who will assert that the item or person under the magnifying glass of being the best, the worst, the mightiest, etc. is not deserving at all and that the honor (or whatever) should, in fact, go to another person, place, or thing. When these absolutes are applied to the arts, which really shouldn’t be judged that way, then it can all become dicey indeed.

In line with all of this, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has bestowed its award on the worthy (or not) for the better part of a century. No organization should know better the pitfalls of naming absolutes, since that’s what awards do by their very definition. Keeping that in mind, it is no surprise at all that every year, without fail, there are some (often many somes) who proclaim that the Academy doesn’t know what it’s doing or is doing it for the wrong reasons and the best was not rewarded at all.

All of this leads to the point of this article. While the idea of simply naming a group of works or people as outstanding and simply saying that good jobs were done and leaving it at that is admirable, human beings thrive on the excitement of competition and the ideas of winning and losing.

The National Board of Review, the oldest US organization awarding good work in film, tried just naming a list of deserving works and workers in film in 1943 (as did TV’s Emmy awards in 1966 and which the distinguished George Foster Peabody awards, TV’s highest honors always has) and had to go back to competition the next year due to lack of interest. However, as stated people often get mad if something/one they consider deserving doesn’t win.

Sometimes, such as the case of 1952’s Best Picture winner, The Greatest Show on Earth (a winner due far more to blacklist era politics than anything else), there is no logic or excuse in terms of quality.

However, there are a number of films with the term “Oscar winning Best Picture” attached to them that, if not the best, are really pretty decent films, and might well be thought of as such if that onus wasn’t on them. This article wishes to focus on those films. The thesis here isn’t that they deserved their awards, just that they deserve a break.

1. Cavalcade

Perhaps the Academy’s greatest flaw throughout the years is the fact that the members often vote with an eye towards posterity, thinking often about how choices will look to future generations, thus causing those members to play it safe and go for safe-sounding prestige efforts which will surely reflect glory back upon the choosers.

Going for Art with a capital A sounds good but that can be so dicey since art can so easily be confused with pretention and, also, those trying for art for art’s sake (as MGM’s motto supposedly exhorted) can so often create something with no pulse at all. That was all brought into play with the choice of the 1932/33 season (the last year the Academy used a theatrical season calendar).

That period of time brought some fine, lively films. The horror/special effects classic King Kong and the eternally fun, low-ish down musical 42nd Street still live on vibrantly in popular culture (though only the latter was even nominated).

If one prefers a higher brow, Little Women, a case study in how to adapt a genteel literary classic and still have it come out interestingly was a nominee, though, sadly, Queen Christina and Dinner at Eight, two other efforts which could be labeled “prestige” didn’t get noticed at all (the timing of the calendar might have caused that) and those films still look wonderful. Then there is the winner…. Cavalcade.

Due to the fact that Twentieth Century Fox very, very rarely released the films made before two companies merged to create the studio as it’s known to this day (the companies being Fox Films and Twentieth Century Pictures) in more recent times until just lately, and, also, due to so many of those early films being lost in a fire in the late 1930s, Cavalcade was unseen for years.

The film was an adaptation of a rare dramatic play by British playwright Noel Coward, one of the great theatrical wits of his century. The play traced the (mis)fortunes of an upper class London family during the hectic early years of the 20th Century, after leaving the peace of the preceding century, and having every big cataclysm of the day hit them (even the sinking of the Titanic).

It was a big hit in London but, significantly, never made it to North America, let alone Broadway, since the work was considered too Anglo-centric to be of interest elsewhere. (However, a decade later Coward and then-young director David Lean reused the idea, this time focusing on a working class family, for the fine and popular 1944 film This Happy Breed, which got no Academy notice.) Well, early Hollywood had a weakness for the stage and US citizens have always had a yen to pair with “the homeland” (i.e. the UK) so a pre-20th Fox films bought the rights and made the film.

This film is surely not to everyone’s tastes. It is quite tasteful in a Victorian era kind of way. Though the husband and wife (Clive Brook, somewhat known to US film goers, and Diana Wynyard, new to both film and the US) are kind to their inferiors (anyone lower class, which is virtually everyone outside of the palace) their behavior unintentionally smacks of condescension.

Also, the way this film enshrines them and their kind might give some a turn (though there is the fact of Downton Abbey in the modern day…). However, it must be noted that the acting is quite good, if of another period (Wynyard was an acting nominee).

The costumes and set design also reflect a lavish sense of both the time in British history the plot concerns and, also, a moment in Hollywood history which won’t come again. There are also, surprisingly, some witty Coward songs in the film, including the classic “Twentieth Century Blues”.

The topper is the expert direction of Oscar winning Frank Lloyd, often a top-notch director of naval dramas, and here giving the story his all. For all this, there are those who will never like this film with the quaint charm of a lovely antique (which it itself is) but, though not close to deserving, it still is worthwhile.

2. How Green was My Valley

Addressing the elephant in the room: CITIZEN KANE IS THE BEST FILM OF 1941. OK, now that that’s out of the way, the winner of the best picture award for 1941 may be discussed.

There is little point in beating the drum for Orson Welles’ great film, often selected Best Film of All Time. Many a book has related how Hollywood resented brash newcomer Welles, how he angered the mighty publisher William Randolph Hurst, and how Hurst’s influence and the fact that Kane, for all its brilliance, is not the most likeable or sympathetic film, all of which doomed it at the box office and killed its chance at winning many or very big awards (it made off with best original screenplay only, a smarmy injoke).

1941, almost as rich a year as 1939, also saw the renowned John Huston (Welles spiritual brother) making his directorial debut with his superlative mystery classic The Maltese Falcon (actually the third version of the novel).

However, the mystery genre was never favored by the Academy so Falcon’s nomination was an honor in itself. Also director William Dieterle’s fantasy folk classic, The Devil and Daniel Webster, unnominated, was a fine piece of filmmaking but a notorious box office bomb (go figure).

All that being said, the winner, the Wales-set period memory piece from the iconic director John Ford, How Green Was My Valley, is actually one of the best films to ever win the award. Ford stands second to none as a filmmaker and Welles himself ran Ford’s western classic Stagecoach many times preparing for Kane.

The previous year had seen two of his films, both now classics, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home (and Welles had chosen cinematographer Gregg Toland to lens Kane based on his work in these films), nominated but they lost to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (not a favored work in his cannon) though Ford himself won for Grapes.

Valley saw Ford working at that same high level. He had worked at Fox Films, then its successor, Twentieth Century Fox for decades by even that time and he had created a crack group of collaborators in front of and behind the camera (which was lensed by the excellent Arthur C. Miller). No studio in Hollywood could create the right physical look for period films better than the artisans at Fox and they outdid themselves in creating the early 1900s Welsh mining town.

In front of the camera were many Ford regulars such as Barry Fitzgerald, Anna Lee, Arthur Shields, Rhys Williams, Sara Allgood (nominated) and Oscar winning Donald Crisp, with the cast being led by Ford’s favorite leading lady Maureen O’Hara (quite radiant), MGM loan-out Walter Pidgeon (easily his best performance), and young Roddy McDowell in the performance which set him on the fine career he pursued the rest of his life.

Past all of that, Ford skillfully held together a film which, by design, didn’t have a strong central plot but worked as a group of highly emotional segments, all directed to maximum impact (though with that sentimentality Ford couldn’t live without but did so well). If this film had beaten out the risible Mrs.

Miniver for the next year’s Oscar it would have looked like a triumphant choice. As it is, this fine picture gets repeatedly clobbered by the weight of having beaten out one of the great pictures of all time.

3. Going My Way

Elephant number two: DOUBLE INDEMNITY WAS THE BEST FILM OF 1944 AND THE GREATEST OF FILM NOIRS. OK, now that is also out of the way. Yes, DI is an immortal film and one of the supreme Billy Wilder’s best works. Also, the classic suspense melodrama, Gaslight (unofficially remade so many times) is also a film to remember. There was also Otto Preminger’s memorable and unnominated film noir classic Laura. Then there is the actual winner, Leo McCarey’s Going My Way.

Quite often modern viewers overlook context when judging the past. 1944 was near the end of World War II (though no one knew that at the time). The war had been long and grueling and, quite often, people tend to get rather sanctimonious in times of great stress. Surely the citizens of 1944 could attest to that fact. For all their many virtues, DI, Gaslight, and Laura are very dark films which are vastly entertaining to modern viewers but didn’t and don’t provide a lot of uplift. By contrast, the winner was nothing but uplift.

Going My Way is a pleasantly sentimental comedy-light drama concerning a progressive minded youngish priest (best actor winner Bing Crosby), who has been sent to take over a failing and troubled inner-city Parrish from the somewhat crotchety, very set in his ways old Irish priest (supporting actor winner Barry Fitzgerald) who has run it for decades.

Needless to say, the warm and easy-going younger man gets the church on track, tames the neighborhood juvenile delinquents (by getting them to sing with him!), solves a few love problems and makes a nice peace with the old priest.

OK, this is cinematic comfort food but, if this sort of film needed to be made, it couldn’t have been made better than Going My Way. A large part of this credit goes to best director winner McCarey. This was his second win in this category, after taking the prize in 1938 for his comedy classic The Awful Truth (still loved to this day) in a year that also saw the release of his dramatic masterpiece Make Way For Tomorrow.

That was the essence of McCarey: he could be funny and dramatic with equal skill because he knew what he was doing and seemed to love people. It would have been so easy to have made the old priest a stock villain to be defeated, but McCarey makes him someone to be understood and the young priest great at understanding. He had perfect players in Crosby, self-admittedly not a great actor but a soothing and relaxed screen presence, and the (somewhat ham) flavorful Fitzgerald, who is a comic delight (and reportedly the actors were nothing like their screen personas off camera).

The pay-off is the finale when the old priest is surprised at his retirement party with the tiny, ancient mother from Ireland he hasn’t been able to see in decades. The director frames the moment so perfectly and simply that resistance is futile. And McCarey could do it over and over. That’s a gift.

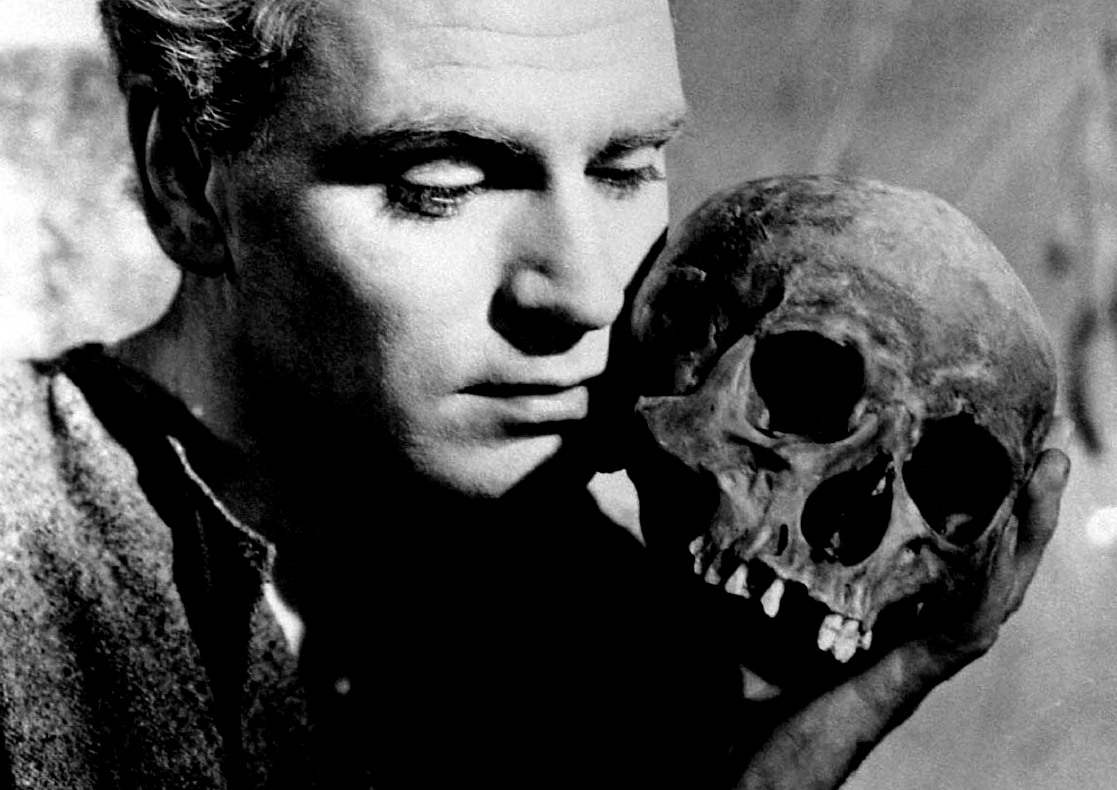

4. Hamlet

Hamlet, the greatest play of the greatest playwright in the English language, William Shakespeare, as filmed by Laurence Olivier, then thought of as arguably the greatest actor in the world: how could the Academy resist prestige catnip like that? As it turns out, they couldn’t. Never mind that John Huston turned in what very well may be not only his best film but one of the great ones ever, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (though he himself did win best director).

Also the superlative British film making team The Archers hit an all-around high with the ballet themed drama The Red Shoes (a triumph of skill and technique over a trite storyline). Also the great European director Max Ophuls offered Letter From an Unknown Woman, a film to stand with his continental masterpieces, not that it got the time of day from the Academy.

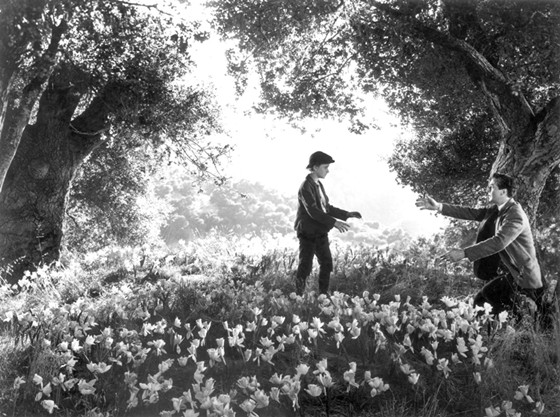

Now, as to the winner, past the films it beat out, critics have always carped about its mere two and half hour running length, eliminating a good deal of the play. However, most Shakespearean plays are edited for time (and when Kenneth Branaugh did film the whole thing decades later it came off as more like a stunt than anything else). The more perceptive critics have noted that the editing is quite skillful and very little of great import was cut.

Also, this was the only one of the four Olivier-Shakespeare films to be shot in black and white (Olivier later claimed to have been having a feud with Technicolor). However, this is one of the darkest of dramas, one that has many similarities to what is now known as film noir. In fact, Hamlet looks very much like a film noir and the cinematography (by Desmond Dickinson) achieves such enormous depth of field that the film almost looks to be three dimensional at times.

Along with that criticism, many over the years have noted that the camera wanders over the empty rooms several times but this makes sense for a story where all major characters will lie dead by the end, so the settings take on greater significance, especially as the camera surveys these now tragic locations at the end. Then there is, surprisingly, the comments on the acting.

Though few had negative comments about Olivier’s performance (though, at 41, he was awfully old to be a student prince) nor for an 18-year-old Jean Simmons coming fully into her own with a fine showing as Ophelia, but there were others to consider.

It will be admitted that Basil Sidney, Eileen Herlie (Hamlet’s mother Gertrude at 28 to a 41-year-old son!) and Felix Aylmer as Polonius, might have been more powerful but the supporting cast is still filled out with man familiar and expert faces (including future horror icons Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, though not together). No, Hamlet may not, in the end, be all that, but it is far from negligible.

5. Gigi

Gigi, the last big hit of MGM’s famed Arthur Freed musical unit, is quite often damned with praise. It always seems to get comments such as “good-for what it is”, “nice, if you like that kind of thing”, or “a nice product of its time and place”. All of that sounds, and is, very limiting. Depending on taste, virtually any film that can fit into a genre could have such comments applied to it.

Musicals seem to have a harder time with this sort of things than most genres since they appeal to a very niche audience. That same year the comedy Auntie Mame, a big hit, was major competition, though comedy is still a niche, too (the musical version of that property was still a decade away).

Though Auntie does have her partisans (many in the gay community), a large number of film fans/students would now prefer the nominated, harder edged I Want to Live! (about capital punishment with an Oscar winning Susan Hayward) and The Defiant Ones (a then-much acclaimed crime based racial drama) and even more, many more, prefer the now classic Sweet Smell of Success (a big all around flop then, despite Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis at their peaks and some fine filmmaking) and Welles Touch of Evil (thrown away by Universal and then available in an almost incoherent studio cut).

OK, these are much harder edged times than the late 1950s and something such as Gigi is perceived to be has a much harder time of it now than it surely did back in that day. However, Gigi is far from a negligible film. In fact, modern cineastes love many of the pictures from the Freed Unit. If the Freed musicals which won best picture had been, say, Singin’ in the Rain (which was not a Vincente Minnelli film) and Meet Me in St. Louis or The Band Wagon (both of which most assuredly were) then there would be little to no dissension.

Well, Gigi, sumptuously set in the fin-de-siècle Paris of the early 20th Century, may seem a bit rarefied put next to those somewhat more homespun (could any famed MGM musical of the time be homespun?) films but it has a lively pulse of its own. The story, taken from a short novel by the great French writer Colette, is actually rather naughty for the day (and even now if one considers the age Gigi is actually supposed to be at the time the story takes place).

Gigi is the latest daughter of a long line of courtesans, women brought up and trained to give sophisticated pleasure to very upper class gentlemen for get monetary reward (yes, upper class prostitutes). Gigi, however, is very natural and unruly and actually captures the heart of the young man chosen for her and makes him go the respectable route (after many fine songs from the renowned Broadway team of Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Lowe).

The cast is flawless with the players being Maurice Chevalier, Louis Jourdan, Hermione Gingold, Eva Gabor and Leslie Caron in the title role giving a performance which almost typecast her out of a career (even more remarkable in light of the fact that she was almost a decade older than the character is as indicated in the script and she still gets by with to the extent that no one ever really questioned the fact!).

In point of fact, everything in this film, the sets, the costumes, the lush cinematography, the orchestrations, Minnelli’s ultra-smooth direction, everything, show the Freed Unit operating in full gear. Perhaps Gigi also suffers, though, from being linked to another (far less defendable and not on this list) Oscar winning best picture: 1964’s George Cukor-directed My Fair Lady.

MGM had concocted Gigi when Lerner and Lowe refused to sell their enormous and then still running stage hit (and wouldn’t for another half a decade). The joke is that MGM ended up with the better film and one that deserves a little more respect.