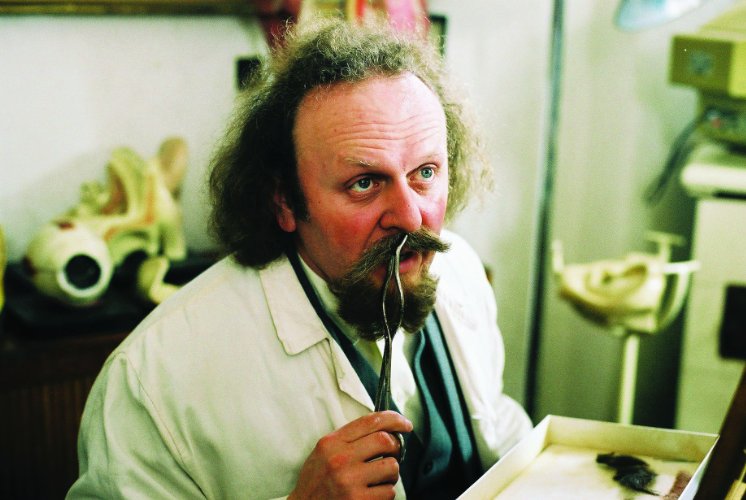

5. Lunacy (Jan Švankmajer, 2005)

Czech filmmaker and artist Jan Švankmajer is known by a certain audience due to his surreal and weird works. He has created many animated short films that have inspired a lot of directors, such as Terry Gilliam. Movies like “Alice” (1988) and “Little Otik” (2000) are acclaimed by many critics and fans because of their inventive style.

“Lunacy” (“Šílení” in its original language) is partly inspired by Edgar Allan Poe and by the works of the Marquis de Sade: it’s a hallucinating and mind-blowing movie experience that is extreme and alienating for any person. Švankmajer is truly masterful in creating one of the most oppressive and unsettling atmospheres ever seen.

The film is an original and horrifying voyage into human perversion and depravity; every scene is unpredictable and brilliantly directed, all of the characters are extremely interesting, and madness is a constant presence. Švankmajer puts the viewer in front of hell on earth, and the movie is disturbing and psychologically frightening because of the unique and absorbing visuals, the director’s mise-en-scène, and the controversially shocking themes.

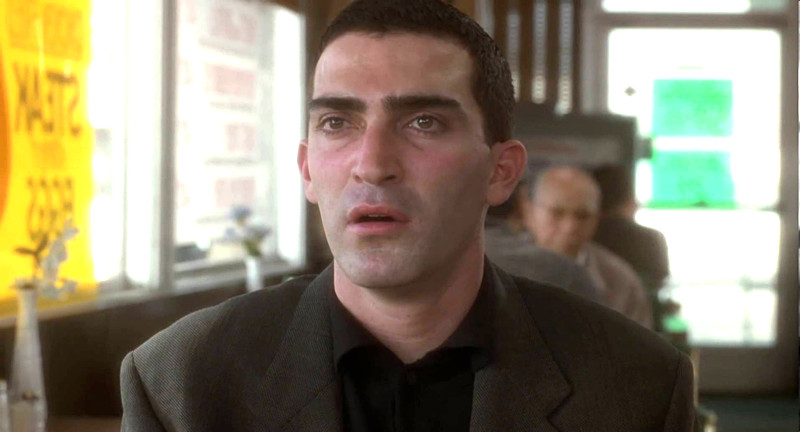

4. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

Winner of the Best Director prize at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, “Mulholland Drive” is considered by many critics and scholars as the best movie of the 2000s. It is also rated above all David Lynch’s other films, and this is not surprising at all due to the talent of its director and the absolute grandeur of the film itself.

Telling the story of an aspiring actress who comes to L.A. in search of success – which intertwines with that of a film director with debts to the Mafia and a woman who has lost her memory following a road accident – Lynch builds a masterful psychological puzzle intended to strongly shake the viewer’s mind and heart. It is a haunting tale of desire, romance, identity and mystery; in the background, the film industry is seen as a place where only money and power are important and where talent and determination are snubbed.

Lynch is a real master of disease and “Mulholland Drive” is the right example of “nightmarish surrealism”: the color palette of the magnificent photography by Peter Deming, the excellent editing by Mary Sweeney, and the immersive and sensational direction from Lynch are sheer perfection. The “diner” scene at the beginning is one of the scariest ever seen, and the movie goes on with many sequences that will torment you for years to come.

Lynch transports you inside his world: Club Silencio, philosophical cowboys, menacing grandparents, love triangles, and many more elements compose a film with unique and disturbing atmospheres that you might experiment just once in your lifetime by watching “Mulholland Drive” – a masterpiece that only a genius could create, a neo-noir drama that’s scarier than 99 percent of horror movies.

3. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

It’s quite difficult to say what’s the most acclaimed or famous film directed by Stanley Kubrick. From the epic sci-fi “2001: A Space Odyssey” to the psychological horror “The Shining”; from the historical period “Barry Lyndon” to the erotic drama “Eyes Wide Shut”; not to forget the satirical black comedy “Dr. Strangelove” and the burning romance drama “Lolita”; he also directed “A Clockwork Orange,” surely his most controversial and talked-about film.

Based on Anthony Burgess’ novel, the movie deals with profound and mature themes such as youth gangs and violence, delinquency, psychiatry, morality, justice, and re-education. Set in a dystopian Britain, “A Clockwork Orange” stages Alex DeLarge and his gang of “droogs” performing what is called “ultra-violence,” and Kubrick uses strong and disturbing images to talk about serious issues that affect society and politics.

Beginning from the awesome long take inside the Korova Milk Bar, Kubrick then builds great suspense and pathos thanks to effective source material and many ingenious and original ideas: the inventive and absorbing style of directing (Kubrick brilliantly used wide-angle lenses and fast- and slow-motion); the dialogue in the Nadsat language; the performances and characters (Alex is one of the best ever); the photography and art direction.

The violence represented is brutal and explicit, but the real talent of Kubrick is to shock with the concept at the basis of the story itself, with the moral and ethical implications concerning society, psychology, world violence, and life. “A Clockwork Orange” is powerful and intelligent, unforgettable and surprising; a film that lets us think how the world goes on and how it should function, how we behave and which conduct we should avoid.

2. The Seventh Continent (Michael Haneke, 1989)

Two-time Palme d’Or winner Michael Haneke made his feature film debut in 1989 with “The Seventh Continent”; partially inspired by a true crime story, the Austrian master directed a movie about the crisis of a middle-class family. It’s utterly extraordinary how the first movie of a brilliant director contains in it all of the trademarks that identify Haneke’s style: long shots, only essential dialogue, rigorous mise-en-scène, realistic photography, and sharp editing.

“The Seventh Continent” is without any doubt one of the coldest movies ever made: an annihilating and harrowing work about incommunicability, the senselessness of existence, and the futility of human relationships. The effect that the movie has on the beholder is devastating: you become depleted of every feeling, and that’s impressive because “The Seventh Continent” doesn’t just disturb you deeply, but it makes you believe that life is empty and that continuing to live does not make sense.

Haneke perfectly used the editing: ellipsis and fragments, brief slices of the family’s everyday life. The viewers do not witness violence, because it has already happened. We just see the consequences of the destruction, the results of human alienation. That’s well underlined by Haneke’s direction, and thanks to his glacial and aseptic style, it does not explicitly explain the reasons for the violence but causes the viewer to ask themselves questions.

“The Seventh Continent” is one of the best debut films ever; a real masterpiece that’s able to disturb the viewer to depression, that criticizes the bourgeoisie in a merciless and powerful way.

1. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)

Italian filmmaker and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini was killed on November 2, 1975: the day before he had completed his last film, “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” based on the book written by the Marquis de Sade and set during the fascist Republic of Salò (1943 -45), in which four wealthy and cruel Italian libertines kidnap some teenagers and subject them to months of torture and atrocities.

The movie was (and still is) controversial because of its graphic portrayal of murder, rape, torture, extreme violence, coprophagia, and sexual perversion. It’s also banned in many countries, having been accused of “obscenity” and “immorality”; however, these are illogical and nonsensical criticisms, because Pasolini didn’t represent brutalities free of charge, but a sensational and mighty cinematic description of a precise era.

“Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom” is a movie about the pornography of power; it’s a shocking report of the tragic and abominable experiences experienced by a group of innocent young people. The libertines believe they can do everything they want with the youngsters; they let out all of their wickedness and they realize all their perversions. Pasolini doesn’t censor anything, but directs a lot of scenes with the most atrociously disturbing images ever put on screen.

The viewer has to cover their eyes many times due to the devastating and truly unsettling vision of what corrupt power can do, and it’s insane and infernal. A pessimistic film that perfectly describes the horror of fascism, corruption, and pure human evil, made by a real human being, a great philosopher and director.