Experience rewards a person in any sphere of life. As humans grow older, their corresponding works of art start to address more emotionally complex and mature themes, as well as the logical and technological prowess that gives them ample power to manipulate the medium of their choice. The film medium is arguably the best, albeit complex, of all media, which can’t be easily mastered. An excellent idea in the paper is often lost in the process of translating to the cinematic canvas.

Every film is necessarily good when conceived in the inner room of a soul. No one wants to make a bad movie. Sometimes an inadequate budget hinders, or it can be the lack of vision and expertise. When this latter obstruction is lifted with a perfect amalgamation of visual and sound, it ends in an intellectually spectacular result worth a discovery. This is a matter of experience; the significant ease that comes with plentiful practice and exploration, leading to a satisfying result.

Every year, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences committee nominates up to 10 movies in the category of Best Picture and rewards the best from them. There is enough controversy regarding the quality of their choices and snubs, but at the very least, they must possess a noteworthy technical honk that can’t be achieved by anyone easily.

Once in a blue moon comes a debut with such a recognizable talent that the whole world notices a potential auteur, and their cinematic offspring is awarded the highest honor: Best Picture of the Year. This article introduces 10 such filmmakers whose debut effort was recognized by the Oscar committee as the best of the year and rewarded subsequently. Here are the directors whose first movies were nominated for Best Picture:

1. Kevin Costner for Dances with Wolves

Kevin Costner makes better westerns than John Ford. It may sound controversial at first, but the history lesson would teach the film buff that despite being the master of the western genre, Ford never won a Best Picture Oscar for his westerns, and Kevin Costner’s “Dance with Wolves” is one of the four western entries to ever win a Best Picture Oscar. It was also only the second film to win that honor after the long haul of the win of “Cimarron” in the 1930s.

It is well acknowledged that Academy is always biased to certain film genres than others, generally disregarding experimental horror, sci-fi, and mass entertaining action-adventure films. At that time, westerns were largely savored by audiences, but their mythical quality was debunked by the critics.

This film changed all that mass critical perception. It won the Best Picture Oscar and the critical reception was largely positive. The epic scale and cinematography were praised, as was the acting by Costner, which is still regarded as one of his best.

The Sioux tribe was so satisfied with the depiction of their culture in the film that they delegated Costner an honorary member of the Sioux Nation. A large number of unknown faces were cast and the running time was considerably longer, but fortune favors the brave and the impact of this bravery is long lasting.

2. Orson Welles for Citizen Kane

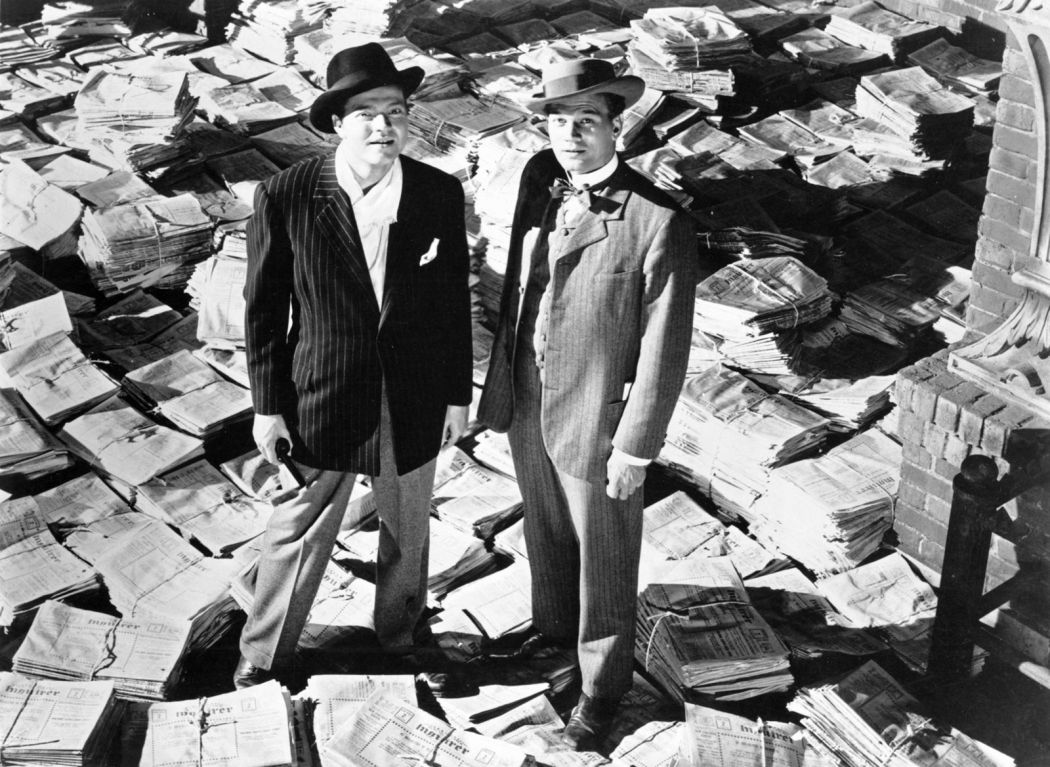

A mention is probably enough for this entry. The withstanding legacy of “Citizen Kane” has long made it an essential film to be viewed and analyzed by the serious and casual film viewers alike. It has reached such a point in the cultural zeitgeist that no stones are left unturned to analyze and praise its legendary cinematic innovations.

Directed by Orson Welles at the tender age of 25, this film continues to top nearly every best film lists made by critics and the public. It famously retained the top spot of the Sight & Sound Best Film list for 50 years, and only displaced by “Vertigo” in 2012. Welles was granted full creative freedom as well as final cut privilege, following his success in the radio broadcast “War of the Worlds,” which is a rare feat in Hollywood even today.

While the stature of innovating the deep focus is contentious, Welles employed various old film techniques of the expressionist school and improved them to use to their best advantage. The disjointed narrative, low-angle shot, sound continuity, and the fantastic montage sequences are some of the instances of cinema at its best.

It seems unbelievable that the initial critical reception was not satisfactory and the Academy decided to reward “ How Green Was My Valley” as the Best Picture instead of “Citizen Kane.” This controversial decision is still a point of fury with critics among the film lovers. However, “Citizen Kane” was nominated for Best Picture along with eight other categories, which is a great achievement for a newcomer.

3. Mike Nichols for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf

This microscopic examination of family relations and hidden secrets is dark and brooding even compared to today’s standards. The apparent happy conjugal relationship of Martha and George is torn apart by two relative outsiders, Honey and Nick, which showed the emptiness that can be created out of physical incompetence and emotional incompatibility.

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor delivered a theatrical but brilliantly staged physical performance in this film. The relationship of this veteran couple is contrasted with the younger version of Honey and Nick and showed them the failed potential of their relationship, in turn destroying the relationship of this young couple, too. Family secrets were revealed one after another as rounds of heavy drinking and scandals follow.

Based upon the stage play of the same name, this film was highly controversial at its time due to its complex themes and vulgar language. The unsuspecting audience of the theatre play, which was in the same way controversial, was skeptical of a successful film portrayal. Mike Nichols took the challenge and made a film that is worth remembering. It is one of the two films that was nominated in every category in the Oscars, which is a milestone to break.

4. Sam Mendes for American Beauty

“American Beauty” was a proper film to label as genre-bending. It is long argued between the critics about the exact meaning of the film and the film’s director Sam Mendes even said that every time he read the script, it appeared to him as something different than the previous reading. Adopted from a script written by Alan Ball, the film addresses various themes of imprisonment, death, beauty, a paternal complex, temporality, and sexual and spiritual awakening.

Depressed by his own work in sitcoms, Ball wrote the script based on his personal experiences of unexpected ecstasy in minor things, and fictionalized certain aspects based on his own family. He assumed that his father was a man who repressed his homosexuality, and by the complex mechanisms that play in human mind, he sought and gain validation by making repressed homosexual an important character of his script. The disgust of petty American life has also been satirized, which is also a manifestation of Ball’s own in his career.

Initially picked and eventually made by DreamWorks for a film adaptation, Ball was involved in every creative process. Impressed by the Broadway work of Mendes, he hired him as the director despite insistence from the producers to hire a more renowned filmmaker. This faith is returned by Mendes in the form of a brilliant minimalistic adaptation that was praised unanimously in the film circle.

The TIFF festival director said that it was the best-received film and it also won the people’s choice award at the festival. It won six Oscars including Best Picture, which helped Mendes to build an impressive resume highlighting this rare accolade as a debutant.

5. Sidney Lumet for 12 Angry Men

It is extremely difficult to make a film that is confined to a limited physical space. That is the reason why filmmakers always try to experiment with different locales. It is important to break the visual weariness of the same setting periodically, and the location shift also helps in effectively transforming the time and space.

A filmmaker has to possess an unexplainably gifted talent to utilize such limitations in his favor. He also has to be a great collaborator as the outcome of such films crucially depends on the effective editing, and great understanding and tempo should be built between the editor and the director for success.

Sidney Lumet did all the things mentioned above and more. It should also be noted that he only had television credits in his name prior to doing this film. Hired by Henry Fonda to make a film adaptation of a teleplay by the same name, he had a gigantic task to perform. The resulting film was an absorbing courtroom drama with only three minutes outside the same setting, featuring 12 unnamed characters as protagonists.

Like “Citizen Kane,” it is also a critical favorite and is still regularly featured on favorite film lists. The film was nominated for Best Picture along with two other categories. It ultimately lost the award to “The Bridge on the River Kwai,” but won accolades in several other places, including a Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.