9. My Brother’s Wedding (1983, Charles Burnett)

Life is all about choices and the smallest ones can have the most profound personal repercussions. A master-piece (capturing small“/uncinematic” moments of life rather than reptilian-formulaic “plot twists/”explosionfests/“socially-important-events”), filmed in Los Angeles’s (Af-rican-American/Latino) Watts neighborhood, one of the poorest places in the United States, that is not really and primarily about race or even class.

Dealing with the same emotional complexities and universal states of confusion that just-might-as-well be found in a Henry James, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Leo Tolstoy, D.H. Lawrence, or George Eliot novel about very-white-aristocrats, with only 500 IMDb, it tells of a man who, struggling-personally, comes into conflicts with his upwardly-mobile-lawyer-brother (whom he detests) and well-to-do fiancé. He is reluctant to be the best-man at their wedding. Having to make the deadly decision of whether to attend said wed-ding or his best friend’s funeral, both set at the same time, he ends up screwing-up both.

10. The Rules of the Game (1939, Jean Renoir)

As critic Alexander Sesonske writes in his Criterion Collection DVD insert, “[l]uxurious town houses define the so-cial setting of the film, and two remarks reveal its moral climate: ‘[l]ove as it exists in society is merely the mingling of two whims and the contact of two skins’ and ‘[t]he awful thing about life is this: everyone has their reasons[,’ e]veryone has their reasons, but in The Rules of the Game, the reason is always the same: I love her/him[, t]he dif-ferences lie in the acts each character believes this reason justifies[, t]hese range from suicide to murder.”

11. The Ascent (1977, Larisa Shepitko)

Late Ukrainian master filmmaker Larisa Shepitko’s (Лариса Шепитько, 6 January 1938, Artemovsk, Ukraine– 2 July 1979, Kalinin Oblast, Russia) films remain largely-unseen outside serious-cinephile circles. 1966’s Крылья, which has only 1,277 IMDb votes, is a tender portrayal of a once-famous fighter-pilot’s ageing-process and difficulties in coming-to-terms with her growing irrelevance, while Восхождение is a truly-harrowing emotionally-profound portrayal of a Soviet soldier’s, in WWII-Belarus, cowardly decision to be-trayal and join the Nazi occupiers rather than be killed, all his misgivings and inner processes shown with deep emotion.

In Michael Koresky’s, writing for the Criterion Collection DVD insert, words, “[s]tarring beloved character actress Maya Bulgakova as a [WWII] fighter pilot turned headmistress, Wings heartrendingly brings to light the inner life of a forty-two-year-old woman who must reconcile remembrance of her il-lustrious past with her drab present reality. Shepitko brilliantly expresses this by con-trasting her character’s stifling quotidian experiences, marked by claustrophobic inte-riors and tight compositions, with heavenly, expansive shots of sky and clouds, repre-senting the freedom and exhilaration of her flying days, and Bulgakova effortlessly inhabits this stern but reasonable woman with empathy and surprising humor[, Wings] remains most effective as a finely detailed portrait of a woman looking back wistfully, made by another woman, full of promise, just looking ahead[, a]t once a visceral, earthy evocation of life on the ground during [WWII] and a momentous, spiritual Christian allegory, The Ascent [drags] the viewer alongside two peasant Byelorussian soldiers, Sotnikov and Rybak, as they attempt to evade, and finally are captured by, marauding Nazis[, f]rom the film’s opening images of telephone poles haphazardly jutting out of snowdrifts like bent crosses, Shepitko, with cinematographer Vladimir Chukhnov, plunges [nightmarishly] blinding whiteness, a physical and moral winter that envelops everything in its path—except, ultimately, the victimized and beatific Sotnikov, whose slow journey toward death brings a strange enlightenment[, s]uch redemption eludes Rybak, whose ruthless desire for survival puts him at odds with the Christlike martyr Sotnikov, and Shepitko charts their twinned passages to darkness and light with a stunning arsenal of aura.”

12. The Red and the White (1967, Jancsó Miklós)

Csillagosok, katonák, which only has 2,712 IMDb votes, was originally-commissioned by the Soviets with the idea-in-mind that it should glorify the Bolsheviks. Jancsó Miklós’s anti-heroic re-sult, about Hungarian volunteers in WWI-Russia joining to assist Bolsheviks, ended-up being censored in the Soviet Union for being as-far-away-from-the-intended-hagiography-as-possible.

The fact that this film is being filmed with the camera being merely-functional (a recording-tool rather than an originator-of-instant-meaning-and-knowledge, Hollywood-style) and static for very-longwinded periods of time and with no “cinematic-expression/gaze/devices/languages” being used, focusing instead on acting, emotion, dialogue, and human interactions and shifts i.e. exactly like a “merely-filmed play,” should serve as hint enough for those thinking IMDb’s Top 250 are “underrated” and actually-socially-eclipsed-by-“foreign/boring”-art-films.

13. Eden and After (1970, Alain Robbe-Grillet)

Little-known experi-mental/avant-garde-filmmaker Alain Robbe-Grillet, like Jean-Marie Straub/Danièle Huillet, was one of the few directors associated with the French New Wave move-ment not to fall into the trap of imitating Hollywood’s formalist-“cinematic-gaze/expression/devices/language” empty-method of meaning-formation.

He actually made good and interesting films, paying attention step-by-step/within-the-flow only to bodies, dialogue, faces, emotions, vocal/verbal tones-and-turns, feelings, psycholo-gy, etc., while ignoring the nurtured urges to try to pin-and-pigeonhole it-all-down to some grand theme symbolically-metaphorically or to interpret it via “cinematic lan-guage.”

His films, like those of Walerian Borowczyk or Nagisa Ōshima, are a test of the viewer’s intelligence. Sincerity, candor, and willingness-to-come-to-terms with non-taken-for-granted and counterintuitive knowledge about one’s self, after looking in the uncomforting-and-challenging mirror, are the name of the game here.

Every viewer must hold to their most-unconscious-desire and submit themselves, after read-ing synopses, into an expectation-free adventure becoming surprised over-and-over-again to discover how their emotional and physical-visceral responses to the actions depicted on-screen turn out to be the exact opposite of what they expected upon hear-ing about them.

1963’s L’Immortelle, which only has 759 IMDb votes, deals with a man meeting a secretive woman (who-may-or-may-not-be involved in some conspira-cy-ring dealing in kidnapped women used as prostitutes), losing her, and, while final-ly-locating her, just before she can explain her disappearance, she is killed in a car crash while he is in the passenger seat; 1966’s Trans-Europ-Express (which only has 1,117) with a filmmaking-crew to whom it occurs that the drama of life aboard the train presents possibilities for a film, so they begin to write a script about dope smug-gling, all-the-while involving elements of erotic fantasy; 1968’s The Man Who Lies/L’Homme qui ment (which only has 553) with the bizarre sexually-sadistic ex-ploits-and-fantasies of a man reinventing himself by lying, all this macho-immaturity, maudlin self-aggrandizing brouhaha, states of middle-aged emotional confusion, or adolescent-like nostalgia for an imagined lost youth, and self-deceiving masks one-wears-so-tightly-they-become-more-important-than-what-is-beneath-them à la John Cassavetes’s Faces (1968)., lying in an attempt to hide from unspecified foes; while probably his best film, L’Éden et après (plus its interesting 1971 “remix,” N. a pris les dés…, one of the few times in cinematic history during which a director remade their own film with unused takes, which only has 162), which only has 798, is one of the greatest statements ever-put-to-celluloid (made just-after-1960s-France, after-all) of the emotional immaturity of adolescent rebelliousness masquerading as “change-the-world” politics and social consciousness, dealing with a group of French university students involved in surreal/sadistic-sex-games.

14. Landscape in the Mist (1988, Theodoros Angelopoulos)

Late Greek master director Theodoros Angelopoulos’s (Θεόδωρος Αγγελόπουλος, 27 April 1935, Athens, Greece – 24 January 2012, Piraeus, Greece) masterpieces are little-known out-side serious cinephile circles.

A longwinded presentation of several actors merely-speaking for a lengthy time while the camera does not move and no artifi-cial/manipulative “cinematic-language” is involved, in other words, the dreaded “merely-filmed-non-cinematic-literature-and-theatre,” not only has a much greater ca-pacity to teach than any Hollywood mode-of-filmmaking but is more dramatic than any car-chase.

His long-takes, consisting of less-than-a-hundred in films stretching-out to four-hours, deal with the passing-of-time and complex/confusing emotions as guilt like no other, and would probably not appeal to those for whom cinema is “entertain-ment” and whose conception of it is merely-mercantile i.e. to those who see films as mere-money-making.

1970’s Reconstitution/Αναπαράσταση (which only has 825 IMDb votes) deals with a woman murdering her husband with the help of her lover, while judges, policemen, and journalists try to reconstruct and understand a news item that escapes them; 1972’s Days of ’36/Μέρες του ’36 (which only has 693) with a petty criminal and smuggler (as-well-as police-informant/agitator) taking a parliament mem-ber as a hostage inside his cell; 1984’s Voyage to Cythera/Ταξίδι στα Κύθηρα (which only has 1,666) with an old communist returning to Greece after 32 years in the Soviet Union; Τοπίο στην ομίχλη, possibly his masterpiece, one of the greatest portrayals of the soul/psyche of a child ever-caught-on-screen, is about two children looking for their father; 1991’s The Suspended Step of the Stork/Το μετέωρο βήμα του πελαργού (which only has 1,544), starring Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau, with a re-porter stuck in a border town with an overcrowding of refugees; 1995’s Ulysses’s Gaze/Το βλέμμα του Οδυσσέα, starring Harvey Keitel and Erland Josephson, with a filmmaker finally-returning to his home-country where former mysteries and afflic-tions of his early life come-back to haunt him; 1998’s Eternity and a Day/Μία αιωνιότητα και μία, another great portrayal of the soul/psyche of a child, is about an ill poet (a ravishing/riveting Bruno Ganz) meeting a boy on the street, an illegal-immigrant from Albania, who goes on a journey with him to take him home; 2004’s Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow/Τριλογία: Το λιβάδι που δακρύζει (which only has 3,574) with refugees from Odessa arriving somewhere near Thessaloniki, while children Alexis and Eleni grow up and fall-in-love; while 2008’s The Dust of Time (which only has 1,351), starring the talented Willem Defoe and Michel Piccoli and the beautiful Irène Jacob, is about an American film director of Greek ancestry who makes a film that tells his story and the story of his parents, unfolding in Italy, Germany, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Canada, in which the main character is again-that-Eleni, who is claimed-and-claims the absoluteness of love. All these gems just vie for some new au-diences/discovery.

15. The Thin Line (1980, Michal Bat-Adams)

The highly-reviled (by tes-tosterone-fueled-perpetual-adolescents/dudebros, comprising most film-journalists, infatuated with technical/technological-tricks and uninterested in emotions, who get exceedingly-angry everytime they encounter a “non-cinematic-mere-filmed-literature/theatre-without-utilization-of-cinematic-gaze/devices/expression-or-language” in which emotions, whether characters’s or audiences’s, and the difficult work and actual-life-experience-based-knowledge about human-beings, rather than how cameras operate, required to understand them step-by-step-and-perceptually/perceptively-within-the-flow, rather than visual shortcuts instantly-telling the viewers via camera-tricks understandable within two seconds even by teenage boys how characters feel or how audiences should feel, are emphasized) Israeli directress Michal Bat-Adams (מיכל בת־אדם) is one of the most aesthetically-“feminine” (not feminist) directress in the his-tory of cinema (obviously the reason she is so reviled by macho journalists, preferring explosionfests to supposedly-“minor” films dealing with “unimportant” common hu-man interactions/emotions), precisely because her masterpieces eschew the aforemen-tioned visual shortcuts in-favor of human emotions and their complexities.

Little-known outside her home-country, her semi-autobiographical (like most of her filmog-raphy) Follia in aguatto (starring Gila Almagor, probably the most famous Israeli ac-tress, and sporting a measly 15 IMDb votes) is a must-watch for all fans of John Cas-savetes’s 1974 masterpiece A Woman Under the Influence (and which actual/genuine cinephile is not?), dealing (and based on Bat-Adams’s own coming-of-age-story) with the relationship between an eleven-year-old-girl and her mentally-ill mother, who is losing a grasp on reality in the surrounding environment of insensitivity and cruelty, her institutionalization only making things worse for her family; 1994’s Aya: Imagined Autobiography/איה: אוטוביוגרפיה דמיונית (which has only 21) is about a thirtysome-thing film-directress, married-and-mother-of-one, who is shooting a film about her life, the meta-film presenting the story of the filming of this fictional film while intersect-ing within it her dreams-and-delusions from her life and relations with her father; 1999’s Love at Second Sight/אהבה ממבט שני (which has only 12) is an intelligent look at the differences-between-men-and-women, being about a young female photogra-pher infatuated with a stranger whose image she accidentally captures on film; while 2003’s Life Is Life/חיים זה חיים (which has only 15), starring Yaël Abecassis, Moshe Ivgy, Rivka Michaeli, and Hanny Nahmias, some of the most famous Israeli actors of their generation, deals with a fifty-years-old-writer/university-lecturer, married with children, having an affair with a 30-years-old mother, while spending his days-and-nights haunted by his fantasies.

She has also made several other great films, such as 1982’s moving Boy Takes Girl (which has only 46 and which deals with two doctors from Tel Aviv-Yafo joining médecins sans frontières, travelling to Thailand to help out refugees, while leaving their daughter, Aya, aged 10, at a kibbutz where the children are housed and showered by age, though not sex), 1989’s אלף נשותיו של נפתלי סימן טוב/A Thousand and One Wives (which has only 7 and is one of the greatest and most penetrating presentations of possessive male sexual-jealousy ever put to screen, deal-ing with a wealthy middle-aged widower in 1920s Jerusalem, all of whose previous wives have died under “mysterious” circumstances, who marries a naïve 24-year-old virgin, who gets pregnant as a result of sleeping with a local textile-salesman), and 1991’s The Deserter’s Wife/La femme du déserteur (a must-watch for all fans of Lars von Trier’s 1996 Breaking the Waves, starring Fanny Ardant and sporting only 11, it deals with a French concert pianist marrying an Israeli computer-specialist wounded during a battle), though available on legal-DVDs in Israel, are completely-unavailable subtitled-in-English.

16. Persona (1966, Ingmar Bergman)

Few filmmakers are more shrouded in pernicious myths than Ingmar Bergman. As one of the few art-film directors your average dudebro heard about, he has, e.g. in my country’s most-popular film-website, became a Prügelknabe-symbol of said explosionfests-loving-dudebros’s delusion-al/contrived/concocted/Orwellian reality-reversing-myth of themselves as a dispos-sessed-minority-barely-receiving-crumbles, with not-enough explosionfests being made yet with too-much-art-films-in-the-world, fighting the Goliath that is the “criti-cal” establishment’s “snobbish/”“elitist/”“pretentious/”“condescending/”“fartsy” disa-vowal of such material and espousal of “challeng-ing/”“difficult/”“inaccessible/”“boring” filmmakers. Nothing could be more igno-rant/far-from-the-truth: Bergman is-in-fact one of the most accessi-ble/straightforward/easy directors in the art-film canon (while no popcorn-flick-material, obviously, being too “boring” i.e. dealing-with-emotions for and flying-over-the-heads/hearts of explosionfests-loving-dudebros, he is no Patrick Bokanowski or Thierry Zéno either), and few journalists/“critics” past-or-present cared-much-for-him.

Anyone who ever bothered to check even supposedly-“high-brow” “greatest-films-ever” lists-complied-by-journalists knows that the only films that are there are there precisely because of their usage of “cinematic gaze/language/devices/expression” shortcuts-to-understanding-self-and-character, instantly-telling viewers how to feel regarding characters/self and their eschewal of “uncinematic-merely-filmed-literature-or-theatre” actually-dealing-with-emotions, which is exactly-how Bergman was deri-sively-referred-to throughout his career (his lack of overt-“socially-important/”politically-correct/middle-class politics/social-generalizations won him no cookies with the other journalistic camp, “film-theory”).

In other words, had said dudebros ever bothered to actually-read film-journalists, they would have known they think exactly like they do, most obituaries after Bergman’s death in 2007 decrying either his “boredom” (lack-of-explosionfests/interest-in-emotions) or his “talky/uncinematic-merely-filmed-literature-or-theatre.”

We reached a politically-correct-on-steroids/“safe-space/”“I’m-OK-You’re-OK/”“we-are-all-equal/”“sensitive-inclusive/”“nonjudgmental” culture in which, in order not to hurt dudebros’s feel-ings/wish-to-eat-their-cake-and-have-it-still-mentality, in which one wishes to be seen as a cultivated-intellectual, with a refined-knowledge-of-art, gaining all cultur-al/symbolic-capital-without-actually-working/changing-anything-about-oneself, equal in knowledge/taste to those who watched Theodoros Angelopoulos’s complete fil-mography, without ever having watched an opera, read a poem or literary-novel, or looked at a painting (“inferior/”“boring/”“unmanly/”“non-visual/”“retarded”) and with the only films one has ever-seen being super-hero-explosionfests, it is not possible an-ymore to state art-films are superior to said materials or that people who watch art-films know-more-about-cinema/have better-taste than people who watch explosion-fests.

That would be “snobbish/”“elitist/”“pretentious/”“condescending/”“fartsy,” in-fact, even the mere-existence of art-films/people-who-think-they-are-better-than-explosionfests is illegitimate, for the same reason i.e. it reminds them they are not who-they-claim-to-be.

Even on a high-brow site as Taste of Cinema, my previous arti-cles got (on Facebook/Twitters) a few comments such as “hurr-durr, watcha-mean people watching Pedro Costa and Tarr Béla have better taste than me-who-watches-IMDb’s-Top-250-dudebro/brainless/thrillerish/thuggish-explosionfest as-well-as HBO’s-exploitative-gangster/mobster-macho-television-series? Watcha-mean these, with-their-greatest-writing-ever-of-using-a-thousand-F-words-per-hour, are not the greatest-artworks-of-Western-civilization-that-already-eclpised-Crime and Punishment? Watcha-mean Sátántangó, Gertrud, and Melancholie der Engel are superior to ‘no-body-understands-you-and-adult-society-is-just-a-bunch-of-dirty-secrets-and-tricks, so-be-a-real-man, rebel-against-authority, and-blow-something-up’-flicks? Watcha-mean I can’t stay a testosterone-fueled dudebro yet receive social-respect? It’s actual-ly you who hates-cinema/knows-nothing-about-it, so-how-dare-you-to-have-the-gall-to-even-speak-about-what-constitutes-art! I said all-taste-is-subjective-and-nobody-can-define-what-art-is and that art-is-whatever-I-say-it-is, so-it-must-be-true! Real-’Muricans don’t-watch-no sissy/faggy foreign-films, you-sucking-prick!”

This Weltan-schauung is frequently-defended as a populist defence of the common-man’s-popular-culture vis-à-vis elites, yet, as Ray Carney eloquently-said, “[t]hese movies are planned and funded by big corporations to make money[, c]onscious and deliberate corporate contrivances to take seven dollars and fifty cents out of as many pockets as possible[, n]ot anonymous expressions of the voice of the people [but] business deals put togeth-er to make money by a group of millionaire California producers, agents, and venture capitalists[, i]n that sense, [Hollywood-]movies far are more ‘elitist’—less an expres-sion of the concerns of the ordinary person—than any [art-film].”

In other words, these dudebros do not defend the powerless/little-guy but powerful multibillionaires (many Hollywood-flicks nowadays have budgets in the half-a-billion-dollar-range) who do not need their “defences” anyway, not some underprivileged-victim/underdog. Even the most inaccessible/difficult/demanding/challenging and experimental/avant-garde-filmmakers in the art-film canon – e.g. Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, Marian Dora Botulino, Jacques Mory-Katmor, Valie Export, Nikos Georgiou Nikolaidis, Jacques Rivette, Danièle Huillet/Jean-Marie Straub, Frank Scheffer, etc. – by mere-virtue of being middle-class common-men with shoestring/modest-budgets, whose most-popular films have a triple-digit (or even double-digit) number of votes on IMDb and can at-best be shown at an obscure/barely-notable festival-or-two, etc., are overwhelm-ingly-closer to the little-guy’s-popular-culture, by mere-virtue of dealing with their everyday-problems, than Hollywood-flicks concocted for the sole reason of earning-money by powerful-multibillionaires who can get billboards everywhere and screen their flicks under every rock.

Who has more financial/economic/political power in our society? Hollywood’s multibillionaires, or, the few cinephiles, most of whom will die anonymous (who are largely-the-butt-of-jokes-by-dudebros-wishing-to-be-seen-as-their-equals—by-society-at-large-while-only-watching-explosionfests), liking said lit-tle-known directors, none of whom ever-saw-a-dime-from-their-films (and who fre-quently did not manage to even break-even with their shoestring-budgets)?

Critic Thomas Elsaesser, in his Criterion Collection Blu-ray insert, writes that in Persona, still cinema’s best/most-politically-incorrect portrayal of a neglectful-career-woman/“liberated-woman”’s (the beautiful Liv Ullmann) understanding that she missed the joys of life by not becoming a mother, “extraordinary powers are stored and enclosed in the face[, m]otherhood and the maternal are often the key characteris-tics of women in Bergman’s world[, t]here is thus something quite archaic or primal also at work in the women’s confrontation in Persona: the power of being able to give birth or refusing to do so, the labor of parturition and the pain of having an abortion being put in the balance and weighed accordingly,” while in 1982’s Fanny and Alex-ander/Fanny och Alexander, another great portrayal of the soul/psyche of a child (readers are encouraged to watch Bergman’s 1986 The Making of Fanny and Alexan-der/Dokument Fanny och Alexander, which has only 713 IMDb votes, described by critic Paul Arthur [op. cit.] as demonstrating “[w]here conventional movie supplements are driven by purely commercial considerations, here, a self-conscious treatment of the relationship between cast and crew reflects the valedictory nature of the original fic-tion, becoming an occasion not only to document an artist’s last fling behind the cam-era but also to meditate on core aesthetic principles”), according to critic Stig Björk-man (op. cit.) “we find the ten-year-old Alexander [Ekdahl] gazing into a puppet thea-ter, lifting layer after layer of skillfully painted backdrop[, w]e have entered the world of a child, one who sees through and penetrates the protective props of the adult world,” and, according to critic Rick Moody (op. cit.) it is “a big, omnivorous bild-ungsroman about youthful imagination at the moment of modernism’s inception.” Bergman’s works represented an actual popular-culture, that which emanates from common-men.

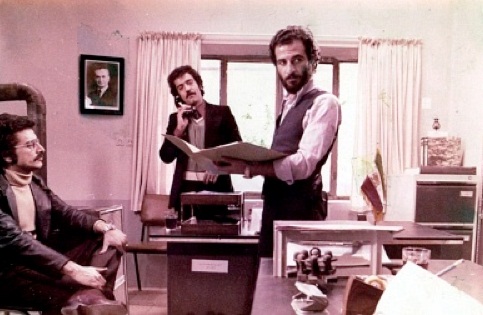

17. The Report (1977, Abbas Kiarostami)

Late Iranian master filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s (عباس کیارستمی, 22 June 1940, Tehran, Iran – 4 July 2016, Paris, France) The Report (گزارش), which has only 482 IMDb votes, was described by critic Godfrey Cheshire III, in his Criterion Collection DVD insert, as “an acidic drama about the collapse of a marriage, and Kiarostami has stated that it was based on the events leading to his own divorce[, its] main characters are a fashionable middle-class Tehrani couple with a young son[, w]hile Kiarostami’s account of their growing an-tagonism and estrangement apportions blame to both sides, his portrait of the husband, a vain, foppish, and self-centered bureaucrat, is especially damning.”