7. The White Ribbon (2009)

Methodically spinning a tapestry of a semi-hidden and semi-agonizing form of moral sickness and murky social dysfunctionality, once again Michael Haneke’s explorative creativity provides an assemblage of queries, instead of providing an object of sculpted and comforting answers. His unsettling, semantically intricate, and optically compulsive film “The White Ribbon” deconstructs the prescient phenomena right before the outbreak of a destructive tempest.

In an amputated village of northern Germany during the early years of the 20th century, a numerically limited and culturally restrained community eerily creeps through rough times by observing, accepting, and dissimulating mysterious crimes that occur periodically. A hypocritical, disturbing law-abidingness defines the prominent citizens of the village, whereas the ill-omened children are constrained to tolerate a distorted status of arbitrary violence and absurd servility.

The story is narrated by the village’s schoolteacher, who makes an attempt to analyze an unwholesome social framework and comprehend the parameters that led to the political burst of World War I. After watching the film through his daunting narration, perhaps you’ll detect a solid manifestation of sociopathy, or perhaps you won’t. Malice is always present, in almost every aspect of life and in every part of history. A sensible explanation of vices is never totalitarian. By deduction, though, evident historical events never start from the scratch. A sociopolitical crisis reflects on the long-term malfunction of a whole.

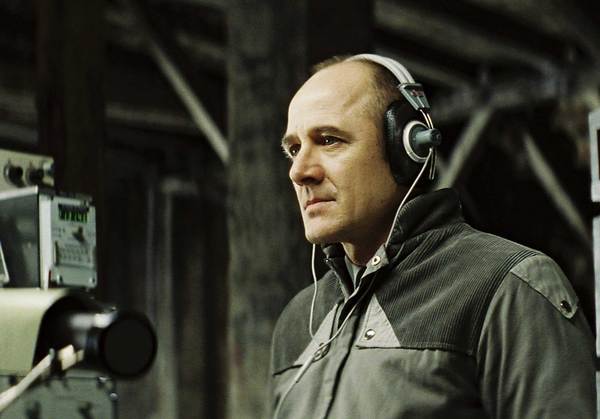

6. The Lives of Others (2006)

Politics are about you and me, about us and everyone around us. For some people, still, politics are about the lives of others. The prominent German film “The Lives of Others,” in its lyrical dramaturgy and profoundly synthesized setting, explicates the motives, the long destructive path, and the definitive impact of a status on its creators, carriers, and receivers.

Some political regimes survive on a deterministic circle of iterability, effectively oppressing the populations. Other regimes are harder to be instated, demanding an anticipatory oppression and ambiguous protection. In East Berlin during the ‘80s, the secret police agency Stasi was created with the aim of defending a status, which originally was meant to bring a change in social life to improve living conditions and benefit the community in its wholeness. Despite the holy intentions, as it usually happens, progressively the sense of power wrecks everything.

Gerd is one of the secret agents. His post is at the basement of a building, in order to spy on a partisan that may be disloyal. He sits behind a glass wall with his headphones, constantly listening to the drama writer talking with his girlfriend, living his indoor life, existing, even breathing. An essentially lifeless man, seeming completely deprived of personal activities, relationship, and needs gradually sinks into the pithy, emotional, and intriguing life of his victim.

Every form of civil bondage is horrid, physical, mental, and ideological. The spied-on writer and his charming mistress are in a way victimized, since there’s nothing kept secret for them behind closed doors, not even their thoughts.

This film, however, is about Gerd, the most tragic victim of the presented situation. He doesn’t realize his grim existence, but he has sacrificed every part of himself for the sake of a misleading hope. Through a restless silence, “The Lives of Others” projects Gerd’s hurt emotional world, hushed desires, and ignored necessities.

5. The Great Beauty (2013)

It’s said that Paolo Sorrentino’s “The Great Beauty” is a modern variant of Federico Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita.” Indeed, Jep Gambardella’s lost facial expression reflects on Fellini’s era of inspirational crisis and confusing backlash to the blinding world of spectacle. But aside from this common direction, Sorrentino’s greatest film, instead of emitting a “Felliniesque” ambience of nostalgia and introspection, explores the idea of beauty in every aspect of life.

In contemporary Rome, a city that expresses both the glory of its past and the decay of its present, Jep is a wealthy, marginally middle-aged man who wishes to be a prolific and acknowledged writer. Instead of focusing on his writing, though, Jep suffers from a lack of inspiration and mental disarray, whereas the sole book in his entire career was a commercial disaster.

Still in search of his real self, despite his advanced age and longstanding experience in Rome’s demanding middle-class, Jep refuses to accept his faded youth of body and soul, seeking some juvenile satisfaction in his unbridled nightlife, embellished appearance, and excessive nihilistic intellectual dialogues. What he actually struggles to accomplish is a comprehension of beauty’s substance. He means to reach the real, deep, and incorruptible foundation of beauty that is hidden behind a facade of askew images.

Jep, in his demythologized and somehow ludicrous figure, is a tragic character. He’s a man of powerful original ideas and wonders, which were lost in the process and led him to the opposite aspect of his real aspirations. Jep searches for beauty by ravaging and denying it. But in his pretentious world of thin esthetic quality in every sense, humanity’s charm can be found in deformed bodies and in an aged, almost discarnate face that survives through an insoluble spirit.

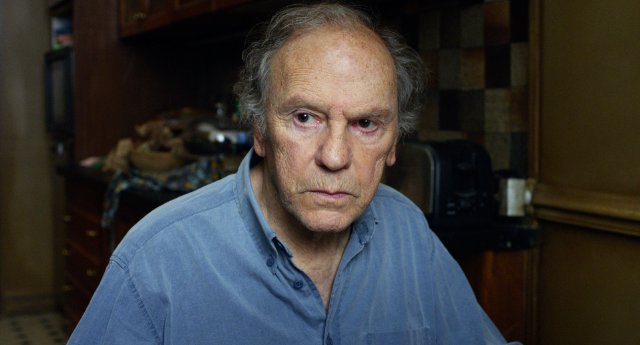

4. Amour (2012)

One of the most devastating, deeply romantic, and sincere films of the 21st century, Michael Haneke’s “Amour” is a homage for life’s purest ingredients: art, creative heat, passion, and love. Putting into the spotlight an old couple approaching the end of their mundane days, the film elaborates on the rough decision of leaving someone precious to perish, over expanding a self-tormenting and unavailing life for egoistic reasons.

Anne and Georges have spent a lifetime together, sharing the same passion for music and raising their daughter. They have both dedicated their forces to sacred values, imparting music and contributing to the perpetuation of a significant culture. Currently, they are old enough, essentially having nothing more than one another.

Suddenly, in the mentally numbing way of such a life-changing event’s occurrence, their peaceful and pithy life is violently interrupted by a stroke. Georges, unable to disrupt a baneful progress, observes his wife losing herself day after day. From her first obstacle of playing the piano, until a gradual penalization of her body and mind, Anna becomes a captive of her outworn physical existence.

Haneke, in opposition to his frequent cinematic climaxes of mystery, reveals the film’s finale from the beginning. Georges and Anne have shared an incredible love for countless years. He could have never done something different but liberate the love of his life from her unfitting material binds. Stripped of a former female physical beauty, Anne is lying in between uncountable rose petals. Georges is now practically alone, but his respect to his memories will keep him graceful until the end of his lonely days.

3. The Turin Horse (2011)

Béla Tarr’s terrors about this world’s fate are underscored in his final film, eternally echoing in the cinematic universe of philosophy and meaningful pessimism, through its thundering silence. “The Turin Horse,” on a first level inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s emotional outbreak due to a horse’s mistreatment in Torino, shares the same exasperation in relation to human vices and effortless stiffness.

The land is vast and infertile, lying unchangeably on a flat ground. An old man and his daughter repeat the same simplistic activities during their long empty days, merely attaining the gloomy scope of a completely stripped survival. Their only weapon, a crippled horse, is moribund. The nature is restless, enduringly warning these fruitless humans for their forthcoming end. As if van Gogh’s potato eaters have enlivened, the protagonists unsatisfyingly eat the unique daily meal of a boiled potato, unaware of their land’s potential disaster.

The film’s earth is angry. Destitute of a substantive present and a future, this world regrets the mistakes of a malicious and morally careless past. Its inhabitants share a hostile homeland and sustain a sultry spiritual emptiness. Tarr’s epilog could be construed as a notice of humanity’s possible Machiavellian plunge, or as a lyrical portrait of immorality and resigned grace. Nevertheless, in its breathtaking black-and-white photography, technical distinctiveness, and psychographic simplicity, “The Turin Horse” inflames various dark wonders.

2. Leviathan (2014)

The battle between socially weak individuals and the merciful beasts of a pretentious democracy has been repeated again and again in modern history. “Leviathan” is a staggering story about Kolya, a humble man who asked for nothing more than keeping his strenuously earned possessions for his family. But since the city’s greedy major desires his land, Kolya is doomed to be defeated.

Kolya is a perfectly delineated character to sympathize with. He’s a down-to-earth, hardworking, and caring man, seeking a serene family life. His aspirations steer clear from grandiose plans and American dreams. His house was created so as to host a family, having a view of the city’s impressive seashore. But Kolya’s modest dreams, longstanding toil, and likeable quality are invaluable to injustice’s ruthless face.

In a hostile place, ruled by the absurd legislation of arbitrage and unequal segmentation, our protagonist stands tenuous, unable to gather the proper forces in order to fight back against his unbeatable enemy. Moving through a chilling and rocky territory, optically and evasively, we see Kolya’s repressed thoughts and ignored rights flaming in an irate invisible parallel universe of mental procedures.

“Leviathan” doesn’t provide the externalization we expect. Questioning the integrity of societies, the requital of religion, and the humane prepositions in general, this film reorders the placement of the common acceptable values and unrecorded values in a wide surface of time and cerebral comprehension. More than conquering an ethical and sentimental catharsis, Kolya’s tragedy evokes an obtrusive realization of our place in the social webs.

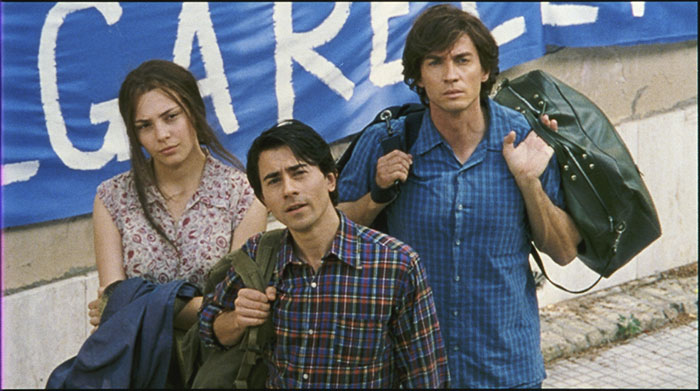

1. The Best of Youth (2013)

A composite mosaic of substantial characters and significant historical events, “La meglio gioventù” by Italian director Marco Tullio Giordana is a unique chance to experience and absorb a film’s reality, progress, and characters, instead of just watching it or at least sympathizing in a limited degree. The story follows the lives of two brothers, from their early 20s until an advanced age, exploring their inner cosmos, as they meet with the people who would define their destinies, and as they assimilate in the maelstrom of Italy’s modern history.

Nicola and Matteo have been raised together, but they differ significantly. They set off a trip with final destination being the northern part of Norway, accompanied by a mentally ill yet charming young girl. After the girl’s detection by the police, Matteo returns home and joins the army in a disappointed mood, whereas Nicola proceeds alone. This is a turning point for them, representing the start line of a long way; a way full of chances, intersections, bonds, losses, and doubts.

Moving from Rome to Palermo and from Sicily to Norway, and dealing with mentality from the wrenching illnesses to the rebellious and self-destructive aspects of spirituality, the film finally hymns the value of living, exploring, and reaching happiness on a personal level. Through its intense contradictions, this lovable piece of the Italian cinema will introduce you to its characters and drift you on their path through life, mistakes, and conquests. Despite its six-hour length, this is a movie you can’t just watch once.