5. The Bridge On the River Kwai (1957)

In typical David Lean fashion, The Bridge On The River Kwai perfectly bridges the gap between action and drama with the director’s trademark aesthetic control and epic scope.

The film takes place in a POW camp administered by the Japanese in Burma with a mix of American and British prisoners. Alec Guiness plays the officer in charge of the Brits held at the camp, Lt. Col. Nicholson, who conducts himself by following the regulations of a captured officer to the letter. He comes into conflict with the camp’s warden, the Japanese Col. Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), who has little regard for the Geneva Convention.

Nicholson and his men are pressured into forced labor building the eponymous bridge and while the men are content to do everything in their power to sabotage the construction, Nicholson sees the project as an opportunity to renew their sense of purpose and ultimately ensure their survival. The third pillar of the film is Commander Shears (William Holden), an American who escapes the camp and then is recruited to go back into the jungle in a commando raid to blow up the bridge.

The Bridge On the River Kwai shows two opposing responses to the prisoner of war experience. Nicholson aims for survival through submission and hard work, while Shears attempts to escape though he knows it will incur reprisals and collateral damage.

The climactic finale is what makes the film rise above. Though there is great heroism on display on both sides, the net result is zero– the bridge is built at great cost and then destroyed at great cost –all of which makes for a powerful statement on the Sisyphean nature of war.

4. The Hill (1965)

The Hill is one of those lost gems that gets unfairly lost to the annals of film history. Forgotten partly because it finds itself wedged awkwardly in Sidney Lumet’s exceptional filmmography between better-remembered classics like Twelve Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon and Network.

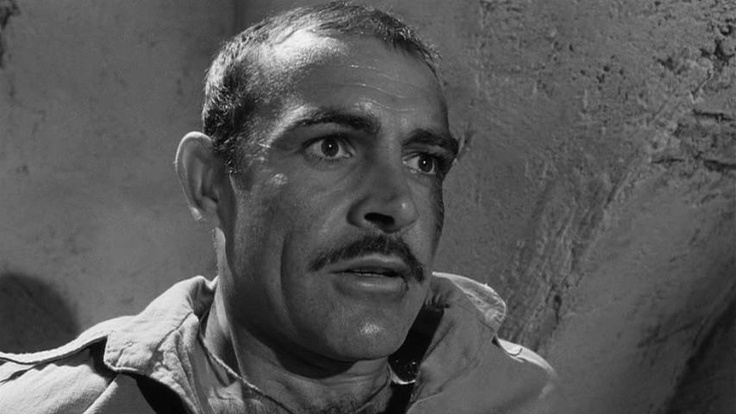

Like Lumet’s best work, The Hill relies heavily on its actors, an incredible ensemble cast of British and American actors anchored by an incredible performance from Sean Connory at the height of his career. Connory, who is rarely asked much as an actor, gets a chance to show off his acting chops engaging in the drama with incredible conviction and ferocity.

Connory plays Joe Roberts, a British tank commander sentenced to military prison for assaulting his superior officer after refusing to send his men on a suicidal attack. The primary means of punishment at the camp is the eponymous hill on which the camp’s sadistic staff hope to “break” their prisoners before drilling them back into disciplined soldiers. However, a particularly sadistic guard lets the punishments get out of hand, resulting in the death of one of Roberts’ cell mates. Connory takes the lead in a quest for justice that pits the prisoners’ resolve against the overwhelming pressure to conform.

The Hill plays off the stereotype of the British stiff-upper-lip to build an articulate argument against silent conformity in the face of abuses of power. The movie should be a classic on the basis of its themes alone, which are as relevant today as they were in 1965, but the message of the film– and its unpalatable ending –make it a complex experience that was too much for audiences of the time.

3. The Great Escape (1963)

Much like A Man Escaped, The Great Escape gives away its finale in the title, but in this case there’s a subversive irony to it. Not content with suffering idle confinement at the hands of the Nazis, the POWs of the film set their sights on tunneling out of the camp in what would be the largest prison break in the history of World War II. Each man is designated a role and given a job to do as they put their plan of tunneling out of the camp into motion.

There’s a certain generation that will never allow the Great Escape to relinquish its position as one of best action films ever. Director John Sturges recast three of his actors from The Magnificent Seven, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn– McQueen and Broson subsequently became go-to action stars of the 60s and 70s.

Some of the sheen of The Great Escape has faded with age, largely due the Hollywood patina being painted on a bit too thick– complete with a baseball catchers mitt, bumbling Nazis and a climactic motorcyle chase –which makes the movie feel less serious than it intends to be.

Still, The Great Escape is one of those films that will never go out of style because it manages to be both an anti-authoritarian film– about getting out from under the fascist’s thumb –and a patriotic celebration of the heroism and sacrifice of the common soldier.

2. La Grande Illusion (1937)

Renoir is a humanist and La Grande Illusion is the clearest articulation of his vision. The film is a masterpiece that has stood the test of time precisely because it deals with big ideas, using the context of POW camps to examine the barriers that we put between one another in every day life. These imaginary walls, whether they are built on the basis of class, ideology, nationality or religion, are the great illusion of the title.

The narrative involves four men each representing a different segment of European society that all find themselves in the same camp during the Great War. The French aristocratic officer, Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay), the German aristocratic officer and warden of the prison, Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), the working-class French airman, Maréchal (Jean Gabin) and the Jewish Frenchman of Polish extraction, Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio).

Boeldieu and his captor Rauffenstein bond over their shared experience even though they find themselves on opposite sides of the war. Maréchal and Boeldieu form a bond based on their shared values as soldiers and both bond with Rosenthal over their shared experience as POWs. By the end of the film, each man overcomes their differences and make sacrifices that strengthen their bonds to one another.

Renoir’s message is so clear and optimistic that it can at times feel naïve, especially knowing what we know now about the terror that was to come with World War II. But this is precisely why Renoir made La Grande Illusion, as a sometimes sentimental salve to the brewing hatred. In context, the film feels like last tragic and desperate plea to a world on the brink of falling apart. It was a vital message then and bears repeating today.

1. The Deer Hunter (1978)

The Deer Hunter follows three childhood friends Mike (Robert DeNiro), Nick (Christopher Walken) and Steven (John Savage) from a small town in Pennsylvania who enlist to fight in Vietnam. While overseas, Mike and Nick are captured by the Viet Cong and forced to play Russian roulette for the entertainment of their captors. They’re eventually able to escape and though Mike makes it home mostly in one piece, Nick is psychologically destroyed by his experiences.

At the time of its release, the film was roundly criticized by veterans for its focus on Russian roulette, a complete invention on the part of the filmmakers. What the critics missed is that the game is a perfect cinematic metaphor for the kind of absurd risk and random death that infantrymen in Vietnam had to face. Watching those scenes can make you feel exhausted, drained and traumatized, which sets you up perfectly to understand and empathize with what the characters go through in the third act.

The Dear Hunter netted five Academy Awards– including Best Picture, Best Director. It made stars out of Christopher Walken and Meryl Streep– earning her her first Oscar. It was tragically, the last role of Streep’s then boyfriend, the legendary John Cazale.

And it announced the arrival of a new powerhouse auteur in Michael Cimino– whose massive ego and equally large cocaine habit bankrupted United Artists in the wake of Heaven’s Gate. The Deer Hunter is an incredible cinematic achievement and easily the best film about the POW experience. It may even be the greatest war film ever made.