5. Dogville – Lars von Trier

Lars von Trier is a Danish filmmaker who is notably polarizing and controversial, and understandably so. Notorious for driving his actors insane in service to his vision, it is even rumored that Björk ate a sweater on the set of Dancer in the Dark (2000) in protest of the director’s unethical working conditions. He is also recognized for saying that he “understood Hitler” at a press conference for Melancholia in 2011.

However, despite these points of contention, he maintains a pretty solid fan following world-wide. The Element of Crime (1984) won the grand prize at Cannes Film Festival for its technicality and was also nominated for the Palme d’Or.

This film put Lars von Trier on the map of global cinema conception. The director has been consistently experimental and innovative throughout his filmography. This technical creativity has transcended into his English-Language endeavors as well. One notable film is the 2003 feature Dogville.

The film stars Nicole Kidman in the avant-garde backdrop of Dogville, a small mountain village depicted on an empty soundstage. Kidman plays Grace Mulligan, a mysterious woman who, while on the run from a company of gangsters, finds refuge in a close-knit town.

Upon discovering Grace as a runaway, the town offers her continued protection if she completes a series of chores for them. Soon the boundaries of the agreement become more and more demoralizing, resulting in degrading exploitation.

The film is meritorious for its cutting edge minimalistic modernism, as well as its inventive Mise-en-scène. Furthermore, Nicole Kidman intuitively resonates in an omnipresent atmosphere of sterility. Overall, Lars von Trier hits the mark with this English-Language feature, and once again confirms his status as a patently daring filmmaker.

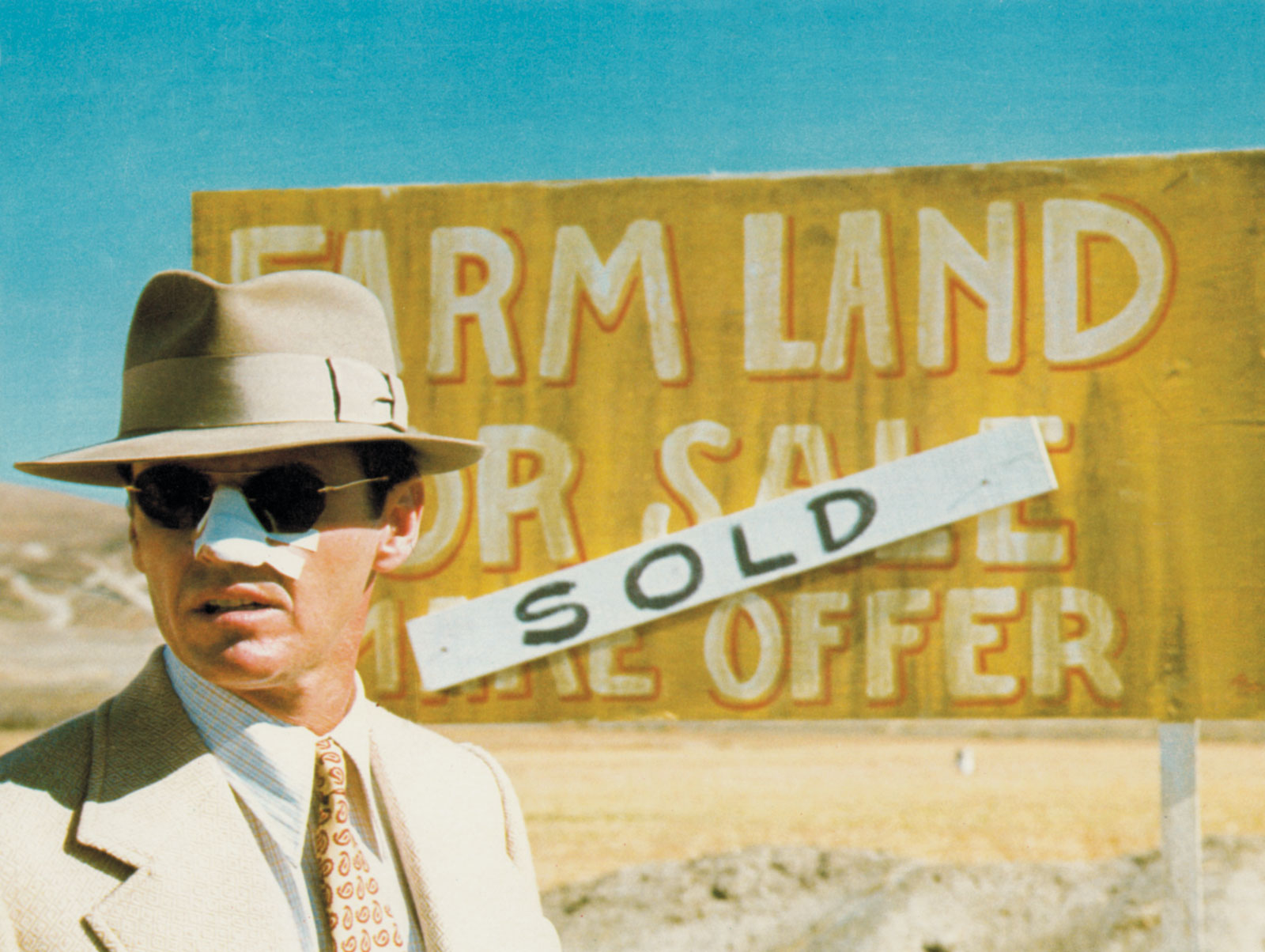

4. Chinatown – Roman Polanski

One foreign director who made a few spectacular english-language films is the infamous Roman Polanski, who has very recently been expelled from The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences due to his fugitive status –having been charged with statutory rape in the United States.

Hesitant to celebrate his legacy, it feels most operative to clarify that the composite nature of film production should depreciate the notion of a director as the sole steward of cinematic enterprise. Especially in Polanski’s case, whose films are so juxtaposed and counterintuitive to his chauvinistic sentiments.

With that being said, Chinatown’s consideration in this list is acceptable through the film’s artistic merit –separate from ethical context. Moving on, the 1974 film Chinatown stars Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway in one of the greatest noir or mystery films to have ever been produced in America.

Set in Los Angeles, the story pertains to private detective Jake Gittes who has been hired by Evelyn Mulwray to investigate her husband, Hollis Mulwray –chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. After following Hollis Mulwray and taking photographs of the man with another woman, Gittes returns to his office to a woman claiming to be the real Evelyn Mulwray –revealing the first woman as an imposter.

The investigation continues in the same vein of perplexity, and with all the tenebrous style of the noir genre. This film is certain to please any great lover of mystery, style, scandal, or Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway –who both perform with indelible charm and sophistication.

3. Amadeus – Miloš Forman

Another foreign director who experienced success domestically before making an English-language feature is Jan Tomáš “Miloš” Forman –originally from Czechoslovakia. Miloš Forman was a very prominent director in Czechoslovakia in the late 60s, and is considered to be an intrinsic contributor to Czech New Wave cinema. He made films such as Black Peter (1964), Loves of A Blonde (1965), and most exceptionally The Fireman’s Ball (1968) domestically before setting his sights on the United States.

Once in America, Forman produced the film Taking Off (1971) which was critically panned and left Forman with a $500 debt to the studio. Downcast and desperate, Forman was fortunately selected by Michael Douglas and Saul Zaentz to produce an adaptation of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest starring Jack Nicholson. Unlike Taking Off, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest was successful critically and commercially. This success paved the way for another adaptation, based on the play by Peter Shaffer, Amadeus of 1984.

The story follows the rivalry of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, played with merry vulgarity by Tom Hulce, and the ascetic Antonio Salieri –played by an embittered F. Murray Abraham. Forman’s adaptation is a delightful treat, as it is a thoroughly charming and engripping depiction of Shaffer’s highly comedic drama. Furthermore, the cinematography is singularly stunning –infusing the mercurial sensibilities of Czech cinema with western academism.

2. The Young One – Luis Buñuel

The 1960 film The Young One is the second english-language film directed by Luis Buñuel following the 1954 Robinson Crusoe. The latter could very well substitute for a position on this list, as it is also an impeccable english-language film made by a foreign director. However, The Young One is special for its connection with the Southern Goth genre quintessential to American Cinema. The same genre motifs are present in Park Chan-wook’s Stoker, reaffirming the genre’s international appeal.

Luis Buñuel was an incredible Spanish filmmaker, known for his contribution to avant-garde surrealism with the iconic short film Un Chien Andalou (1929) –in which he collaborated with Salvador Dali. His other films also kept with the surrealist movement such as The Discreet Charm of The Bourgeoisie (1972), The Exterminating Angel (1962), Belle de Jour (1967), and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977).

Buñuel’s The Young One is a step out of the surreal, as its very grounded in austere reality. The story is set in the bucolic landscape of a quiet island off the Carolina coast. Traver (Bernie Hamilton), a Black jazz musician fleeing from a false accusation of rape from a white woman, stumbles upon the house of Beekeeper Miller (Zachary Scott) and his ward Evalyn (Kay Meersman).

Miller’s partner and Evalyn’s Grandfather having just passed away, leaves the beekeeper in charge of the child’s care. With this new authority, a lecherous conspiracy burgeons in the mind of the fairly solitary man. Traver and Miller, while competing for the young girl’s affections, develop a hostile racial and moral rivalry. The film is a fantastic bestowal to the Southern Goth genre in cinema, made especially extraordinary through the brilliance of Luis Buñuel –one of the greatest filmmakers of all time.

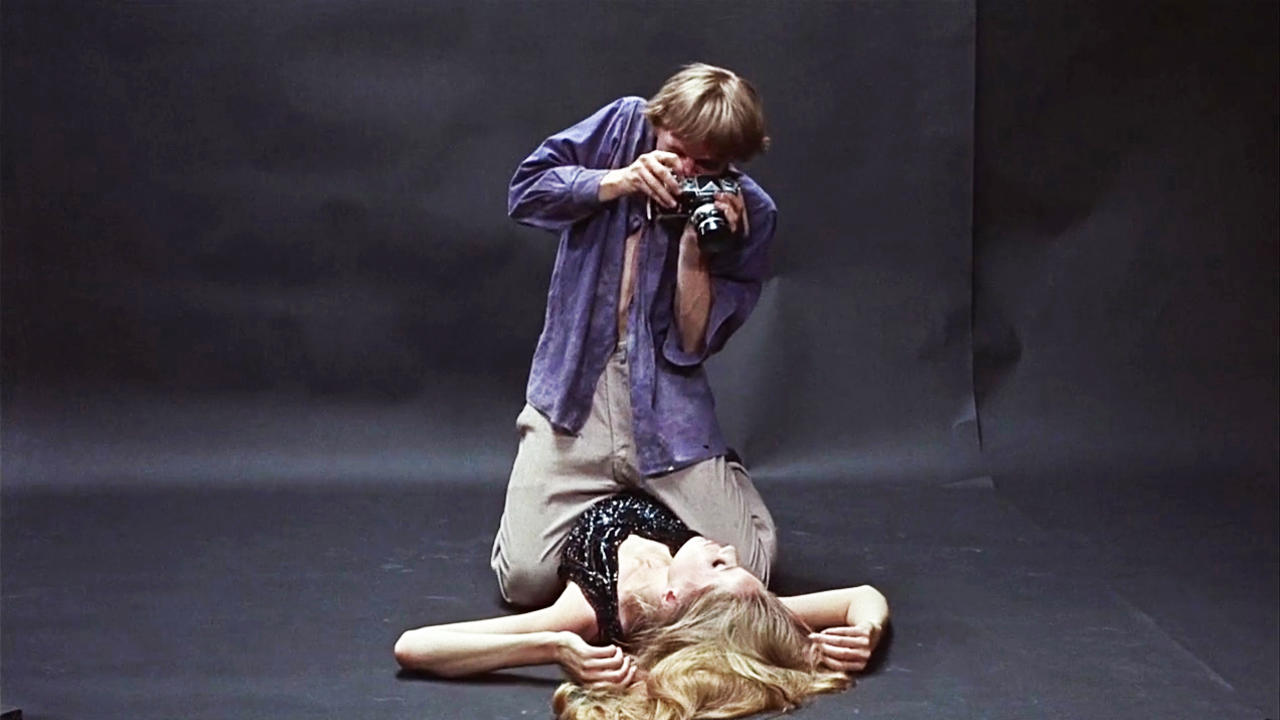

1. Blow-Up – Michelangelo Antonioni

Michelangelo Antonioni is undeniably one of the greatest filmmakers in the global cinematic reverie. Born in Ferrara (the “City of Renaissance”) in Northern Italy, Antonioni’s innate polymathy has allowed the filmmaker a signature style.

With a faculty that had been predisposed to the ethos of design and architecture, Antonioni’s cinematic sensibility privileged mood, image, and design over the conventions of narrative cinema. This accredited him as the central authority in the “cinema of possibilities.”

In Italy, he produced works like Story of a Love Affair (1950), as well as The Adventure (1960), The Night (1961), and The Eclipse (1962). The latter constituting a trisect called the “Trilogy on Modernity and its Discontents.” All of these films are an attempt to depict the alienation of modern man.

In similar form, Antonioni realized his first English-language film in 1966 –Blow-Up. The story is set in London and loosely based on The Devil’s Drool, a short story written by Argentine novelist Julio Cortázar. The film tells a tale of a fashion photographer who is propelled into a world of hazard and mystery, after having taken potential photographic evidence of a murder.

With this British-Italian thriller, Antonioni continued to prove his counter cultural influence –despite his personal cultural displacement. The explicit content of Blow-Up was in direct violation of the Production Code of the 1960s. But because of this particular film’s incredible commercial and critical success, the code was revoked. In lieu of the Production Code, the MPPAA film rating system transpired as a way for cinema to regulate itself –without depriving the public of essential high quality films like Antonioni’s Blow-Up.

Author Bio: Heather is a Communications major with a Chinese minor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and he is also pursuing a film studies certificate. His favorite films include Igmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander, Luis Bunuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Werner Herzog’s Aguirre The Wrath of God, Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express, and Scorsese’s Goodfellas. Other interests include theology, Asian studies, Italian Giallo, Czech avant garde, and Soviet Cinema.