9. The Missing (2003)

1995’s Apollo 13 marks a turning point in Howard’s career, as from that film onward, he’s not hesitant to take cinematic risks, such as doing a western that incorporates an element of spiritual warfare.

The casting of Cate Blanchett is perfect, as she’s not an openly effeminate figure – but rather a mother, protector, and fighter. Blanchett’s relationship with her estranged father, Tommy Lee Jones, sets the stage for the tense alliance she needs to forge to save her daughter. Family dynamics is something Howard often dabbles in, yet he only rarely addresses the parent/child relationship exclusively.

The Missing is one of the few films where this dynamic takes center stage, and although the film suffers from a hint of cliche in that the audience expects that the first 35 minutes are set up for events that will partner Jones and Blanchett, it’s interesting that both Jones and Blanchett are matured adults. The parental relationship is not the typical two different generations clashing, as is often the case in parent/child narratives.

8. Night Shift (1982)

Similar to Grand Theft Auto five years prior, Howard’s second film is also a nonsensical farce, yet walks the tightrope of comedy & romance better than many other films in the genre. As opposed to Splash, the film doesn’t primarily hinge on the blossoming male/female romance. The comical relationship between Henry Wrinkler and Shelley Long is only a segment of the insanity already padded with the sexual frustration and dissatisfaction of Wrinkler’s life.

Night Shift is arguably one of Michael Keaton’s finest performances as his energy not only carries the film, but gives Night Shift an insanity that sets it on a higher tier. Like most rom-coms, Night Shift is predictable – yet Keaton’s unpredictability fuels the picture – making the college party humor acceptable.

After the initial 30-minutes, the opposites of Wrinkler and Keaton complete the ebb and flow of broken relationship ending in companionship. The joining of the two opposites at the conclusion of the first act gives Night Shift room to breathe and allows for the story to elaborate in its unsanity.

7. How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000)

Howard’s most expensive comedy (a production budget of $123 million), has a cinematic gloss opposed to any of his other comedies. How the Grinch Stole Christmas has a richness by means of the make-up, costumes, the sets, James Horner’s score – but most importantly Jim Carrey’s off-the-rocker performance.

As Michael Keaton’s crazed Billy Blaze of Night Shift livens the scenes he’s in, Carrey’s Grinch commands attention for every single frame he’s shot on. As embellished as the film is from Dr. Suess’ book, the adaptation succeeds because Carrey’s performance delivers on letting the audience see him interact with the villagers of Whoville.

The story’s modifications allows for the emotional orchestration of the Grinch’s backstory. The audience knows that the Grinch will eventually steal Christmas, but the inciting incident allows for Carrey’s (arguably correct) denunciation of Christmas frenzy.

While shifting between a faithful adaptation and an amplified backstory, the balance may seem a tad off, yet it reaffirms the Grinch’s intention to totally wipe out the holiday. Therein lies the Ron Howard snag: the juxtaposition of Carrey’s inability to actually steal the holiday and the young Taylor Momsen’s (Cindy Lou) inability to open up the hearts of the adults.

6. Far & Away (1992)

The film is credited as “directed”, “produced”, and “story” by Ron Howard, so it should be no surprise that Far and Away incorporates all the main themes seen throughout his body of work.

The ebb and flow of relationships and/or the love story are generally the catalyst of the dramas, so the banter between Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman has a chemistry that enriches the conquest of the characters, equally giving a comical undertone. Both Cruise and Kidman begin Far and Away with their own agendas, dreams, and opinions about America, but those ideas change as their relationship deepens, not unlike the rivalry seen in Rush.

Cruise’s rise in the streets as an Irishman boxing for money is a preamble for Cinderella Man. From Cruise’s first scene in Far and Away there is a tenacity in his fight for a man of smaller stature; the aggression has a fearlessness. Of course, as a Ron Howard “story,” any and everything that can obliterate Cruise and Kidman’s prospects happens. However, it’s the non-stop fight of Cruise combined with the romantic union with Kidman that makes for a rousing comeback.

5. Frost/Nixon (2008)

Nonfiction movies that side-step main historical events can occasionally do a better job of articulating volumes more about the subject than initially intended. One of the best films about Watergate and the Nixon presidency is one of a story that happened outside of the keynote events of the burglary and the Washington Post’s investigation.

The duality of Frost/Nixon offers one side of Michael Sheen’s (David Frost’s) research team, which is presented in a fascinating light in that the British Sheen/Frost doesn’t initially comprehend the academic liberals’ agitation with Richard Nixon. On the flip side, Frank Langella (Richard Nixon) in retirement shows a man who wants to carry forward and is longing to get back into politics, which tells the viewer something about Nixon’s tenacity.

Errors regularly occur that muddle Michael Sheen’s situation, pushing him towards a “no holds barred” pseudo-debate with the ex-president. A political boxing match, each side with a staff of advisors; not too different from Paul Giamatti’s ringside pep-talks in Cinderella Man. Howard pushes the narrative towards Langella’s emotional breaking, bordering on a character study of Richard Nixon.

4. Rush (2013)

There is a line towards the beginning of Rush where the owner says “men love women, but even more than that, men love cars!!” Despite the intensity of the film, none of Howard’s dramas ever appear to be having this much fun. Is not Rush the exciting spectacle that Ron Howard wanted to make since the days of Grand Theft Auto?

The duality of two lead characters makes for obvious comparison to Frost/Nixon, and although the Watergate topic outweighs race cars, Howard packs Rush with loads of energy and philosophical perspective of the two drivers. Frost/Nixon respects the burden Nixon carries, yet the audience could get the impression that Howard is tipping his hand in favor of Michael Sheen’s character; with Rush, the drama takes no sides to suggest a moral superior.

Chris Hemsworth and Daniel Brühl are polar opposite forces, restless and relentless in their envy (or disgust) of each other. Their respective love interests allow an insight into their integrity as well as another example of how Howard incorporates sexuality into the narrative of his films. Aside from the cinematography, the editing, the dialogue, and music; there are two noteworthy elements that place Rush into a masterclass of cinema.

First, Rush sells its audience on seeing both characters pushed to the extreme, and afterwards they develop an astounding sportsmanlike respect for each other. Secondly, like Frost/Nixon, the two characters get a post-mortem after the “battle”: the final conversation that concludes Rush lays out the philosophies that were spared against each other. Brühl points out that having an enemy is a blessing, which on some level is theme seen regularly in all Ron Howard’s films? The downfall and/or villain gives way to the rise?

3. A Beautiful Mind (2001)

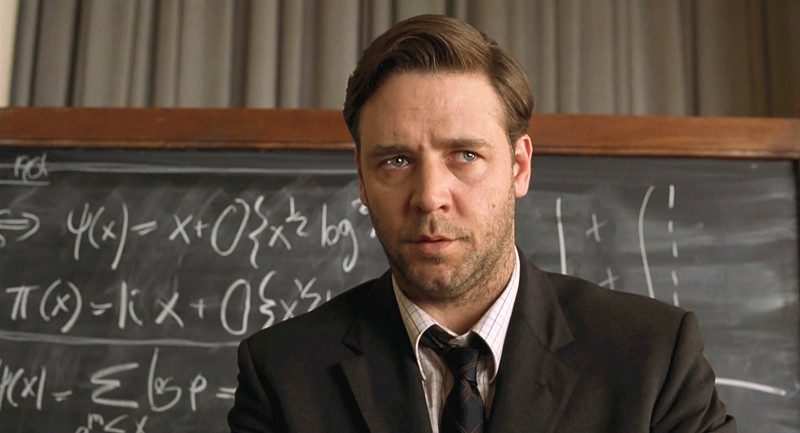

17 minutes into the film and the audience’s hearts are breaking for this strange and disrespectful loner. Russell Crowe is like Jim Carrey in The Grinch in that every time he’s on screen he captures the attention of the audience.

Physically there is a difference between the likes of the introverted Crowe and the macho William Baldwin in Backdraft, or Tom Cruise in Far and Away. Yet all three are stubborn fighters who get beaten repeatedly and continually persist against their obstacles. There’s no boxing matches (Far and Away), dangerous race courses (Rush), or spells of a necromancer (The Missing) hunting Crowe in A Beautiful Mind; rather the battles are deeply internal.

Jennifer Connelly might be Ron Howard’s best love interest. Her poise, soft-spokenness, and confidence is a performance that initially gets overshadowed by her co-star. Yet, A Beautiful Mind is of the era of Fight Club (1999, David Fincher); The Sixth Sense (1999, M. Night Shyamalan); and Memento (2001, Christopher Nolan); where the replay value was something studios were interested in pursuing.

The first time watching A Beautiful Mind, the attention is on the fraudulent goose chase that Ed Harris has wrapped Crowe up in. Yet the second time around, the viewer (already anticipating the deception), will inadvertently shift attention to Connelly. A Beautiful Mind offers a different experience on a repeated viewing – wherein seeing Crowe against the impossible odds of government conspiracy, changes into Connelly against impossible odds of her husband’s delusions.

2. Apollo 13 (1995)

The way in which drama would be inserted into comedy (Splash; Parenthood; The Dilemma), so too the reverse. Lighthearted moments are staged into first half of Apollo 13 before the explosion, allowing for a more distraught emotional experience. Apollo 13 remains one of the most deserving Academy Award wins for editing as the balance and flow of the narrative is perfect.

The intimate scene in the bedroom between Tom Hanks and his son has the necessary purpose of explaining an element of rocket-science to grade school mentality. Once the disaster strikes, the drama becomes all technical with the proper emotion to explain a convoluted situation.

The finale of Apollo 13 is vigorously patriotic without necessarily waving “old glory” in front of the audience. Although in recent decades Howard has turned to Europe for settings, the American dream is such a core element in so many of these stories. How many times has Howard bombarded the protagonists who come out in favor of the American dream? Foreign business prosperity in Gung Ho; a new terrain in Far and Away; reverence for the Native American in The Missing; the second chance of Cinderella Man, etc.

Apollo 13 celebrates the perseverance and ingenuity of the space program. The same way Frost/Nixon is set in the aftermath of Watergate and paints an accurate picture about the subject without showing the main event — so too does Apollo 13 articulate the brilliance of NASA and landing on the moon by showing how they coped with disaster.

1. Cinderella Man (2005)

The film establishes a relatively wealthy, popular, and modest family man who gets it taken away from him. The first act of Cinderella Man pulverises Russell Crowe with a broken hand, decommissioning his boxing license, no work opportunities, and a lack of food for himself and family.

Crowe’s love-interest via Renée Zellweger remains the beacon that encourages him to want to keep their family afloat. The intriguing element of this romance is that Crowe and Zellweger are inseparable lovers; even in disagreements their confrontations don’t result in name-calling or aggression towards each other. Crowe needs her for the family unit: “If we can’t stay together that means we’ve lost! It means we’ve given up!”

The agony of the Great Depression that Crowe goes through alters his perception towards boxing – seeing his profession with newfound positivity and gratitude. Regardless of winning, Crowe’s is met with adversity, chronically reminded how close he and his family can come to death. He fights with tenacity, both inside and outside the ring refusing to settle for less. This stamina hallmarks Howard’s work, yet for Cinderella Man, the biggest conquest of World Champion seems far off – yet conquering one trial after another, Crowe increases his risk and sucess.

Author Bio: Michael Jolls is producer and director to dozens of various projects including 6 Rules; Cathedral of the North Shore; The Great Chicago Filmmaker; and Sell Me This Pen. He is the author of the books The Films of Sam Mendes and The Films of Steven Spielberg, as well as assistant editor on David Fincher: Interviews for Dr. Laurence F. Knapp.