8. Pulp Fiction

When Quentin Tarantino was announced the winner of the Palme at the 1994 Festival, there was instantaneous uproar from the audience. Many critics believed Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski had deserved it for his flawless conclusion to his equally impeccable trilogy “Three Colors: Red”. But “Pulp Fiction” would entirely change the dynamics of the Hollywood mainstream, with non-linear storylines and a vividly stylish use of violence never being so alluring to a mass audience.

The film is document of the absurd antics of the multiple people it focuses on: mobsters, petty criminals and boxing champions. It’s a world unconnected to the real one and yet so fiercely, mysteriously connected in itself; it proves difficult not to eat it all up. Delicious wit, indecorous energy and authoritative performances make this an uncharacteristic acid trip that almost has something for everyone.

Tarantino hasn’t matched his head-spinning, zany authenticity here with any other film, even though they all seem to be coming from the same, vibrant aesthetic voice. John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson were never and would never be better, injecting a magnetic stylishness to the proceedings. But some might find the endlessly fascinating Uma Thurman as the star of the movie. Considering how many people have successfully danced with Travolta onscreen, she is handily the most memorable one.

7. The Third Man

Carol Reed’s “The Third Man” is an unquestionable British classic. Its use of harsh lights and darkened atmospheric camera angles made it one of the most acclaimed films of its time. Voted by the British Film Institute as the greatest British film of all time, its riveting, intriguing undertones still don’t seem to be done with cinema fans across the globe.

About an American man Holly Martins who is hired by one of his friends for job in post-World-War-II Vienna who discovers that his friend is dead upon his arrival in the city. The industrious use of filmmaking in developing an ingenious mystery from that rather dated premise was a ridiculously ambitious attempt when compared to the turgid filmmaking of the time.

While Robert Krasker’s cinematography is the most commented-upon aspect of the film, and deservedly so, Anton Karas’s iconic score is also a palpable, seductive entry into the film’s sensory control of the viewer. Reed’s sharply rendered notes are elusive in their highs and gratifying in their lows.

6. The Conversation

One of the rare character studies that does focus more on the character than on the world surrounding him, “The Conversation” derives all of its strength from the intensity with which Harry Caul reacts to his job as an unusual dread begins to wash out on him when he starts believing one of his recordings betray the details of a murder plan.

Caul lives alone. His isolation is something he dearly cherishes and Gene Hackman’s discomfort as he apprehends a threat to his anonymity is positively scary. It is a performance entirely internal. A nervous pause here, a prolonged stare there are deafeningly voluble. It remains one of the greatest Oscar injustices of all time that the actor did not receive a nomination.

Coppola diverts from his trademark style to chart Caul’s intricate perception with astounding honesty, never allowing us to believe that a world exists beyond his silent musings. It’s become understandably trivial to call it underrated, but perennially overshadowed by The Godfather films that more prominently define Coppola’s career at the time, “The Conversation” always warrants a full-bodied discussion on its merits.

5. Blowup

Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blowup” is quantifiably polarizing. It splits its audience right down the middle. One section believes in its exploration of our perception clouding our vision, and the other dismisses its imagery as wasteful or worse, heavy-handed even. It’s striking in its expression, yes, but also creates lasting nuance that layers the airy, yet tightly controlled film.

The protagonist is a local photographer who treats his subjects merely as such and never as people, and gradually begins to see other people as his subjects too. He, not unlike “The Conversation’s” Harry Caul, believes that he has actually captured a murder on camera. We see everything in the film from his perspective and David Hemmings’s hypnotic performance never loses its grip.

Certain things in “Blowup” which form the crux of the argument that the film is heavy-handed are realized with deep honesty and peculiarly poetic style. For instance how Thomas uses jazz to underscore all his conversations feels something utterly humane and fallible and yet could be misinterpreted for drilling the thematic relevance of the film into the viewer’s head. One may choose to believe either, but the former is more rewarding.

4. Taxi Driver

Martin Scorsese’s love/hate letter to New York City, now often cited as the best film of the 1970s, was highly controversial at the time of its Cannes premiere. Critics were reluctant to embrace its luscious violence, especially that one famous scene at the end of the film. When Scorsese won the Palme, the decision of the jury was questioned by many. The man himself didn’t show up to receive the award.

Over the years, the film’s status as a classic has been cemented over and over again. Included in every list of the greatest films ever made, it has influenced generations of filmmakers with its social criticism, savory cinematography, and bubbling raw power. Countless parodies and spoofs later, it still holds up as a singularly American classic by a film director who would rarely reach the same heights.

The story is of Travis Bickle, a discharged US Marine who is isolated and takes to driving taxis to deal with his insomnia. As his keen, frighteningly piercing eyes observe the city around him, he finds all of its hypocrisy and filthiness enraging him. He is seen plotting the assassination of a politician and attempting to save a local teen prostitute.

“Taxi Driver”, it should go without saying, cannot work without De Niro’s astutely empathetic work. His comprehension of Travis is beguilingly pristine, and his delivery of all those iconic lines is as sharp as a whip. The lean editing is divinely effective while Scorsese’s command on the camera and on the sublime use of bright colors is some of his very best.

3. La Dolce Vita

With both “8 ½” and “La Dolce Vita”, Fellini seemed to be telling to the world: this is how you start a film. But the famous beginning of the latter landed him in trouble. The Catholic Church thought the film was a parody of the second coming of Jesus and condemned it in the Vatican newspaper. Unfazed by this development, the Festival jury still rightfully awarded the film the Golden Palm, once again upholding its prestige.

The film is centered on a journalist called Marcello Rubini who writes for gossip magazines. He follows celebrities, goes to parties, contemplates what the future holds for him in the seven days we experience the world of Rome through his eyes. Bursting with sadness and an unperturbed contentment at the same time, his flawed persona holds gorgeous control.

He is played by Oscar nominee Marcello Mastroianni, who bares everything in the film through his sizable vulnerability and childish sincerity. His Marcello seems to seek escape from his life, but keeps getting deluded back in by the short-lived passion he feels for it. He elevates the film to a new level by working with his gloomy, heavily burdened eyes: something purely stylistic to a skeptic, but ineffaceable to others.

Fellini had desire for aesthetic experimentation with “8 ½”, but with “La Dolce Vita” he appears to be completely at ease with the medium, which allows him to explore philosophical, even spiritual themes. He is benefited by Nino Rotta’s impossible-to-get-out-of-your-head score and the luminous photography of Otello Martelli, creating a sweeping, ethereal masterpiece for the ages.

2. The Tree of Life

Terrence Mallick seems to be going through a phase. Post his return to the big screen after nearly two decades with “The Thin Red Line”, Mallick has been churning out weirdly structured, or unstructured for that matter, somewhat effective and somewhat incoherent visual tone poems that can only be called experiments. While “The New World” was a magnificent one, his career has been full of misfires like “To the Wonder” and “Knight of Cups” of late.

The exception, undoubtedly, is “The Tree of Life”, an epic intercutting of the beginning of the world and its evolution over millions of years with the childhood of a Texan boy that has to be one of the most ambitious films ever made. It is a companion piece to something like Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” as it aims to examine every fabric of the universe, but unlike that stone-cold monument, “The Tree of Life” possesses immeasurable emotional depth.

It might come off as overly indulgent to some viewers. At two hours and forty minutes, and devoid of a narrative, the film can prove to be a difficult viewing. And while boldness of this kind, with the camera almost aimlessly wandering to places it finds of even the smallest of import, Mallick’s vision is triumphantly effective, guided by unearthly work from DP Emmanuel Lubezki.

Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain are beyond description. Every limb of their body is in full understanding of the quantum of the film’s scope. They seem to be effortlessly become the filmmaker’s most impossible dream. The sheer physicality of their work is unlike anything ever accomplished onscreen and their combined efforts make for one of the greatest performances of all time.

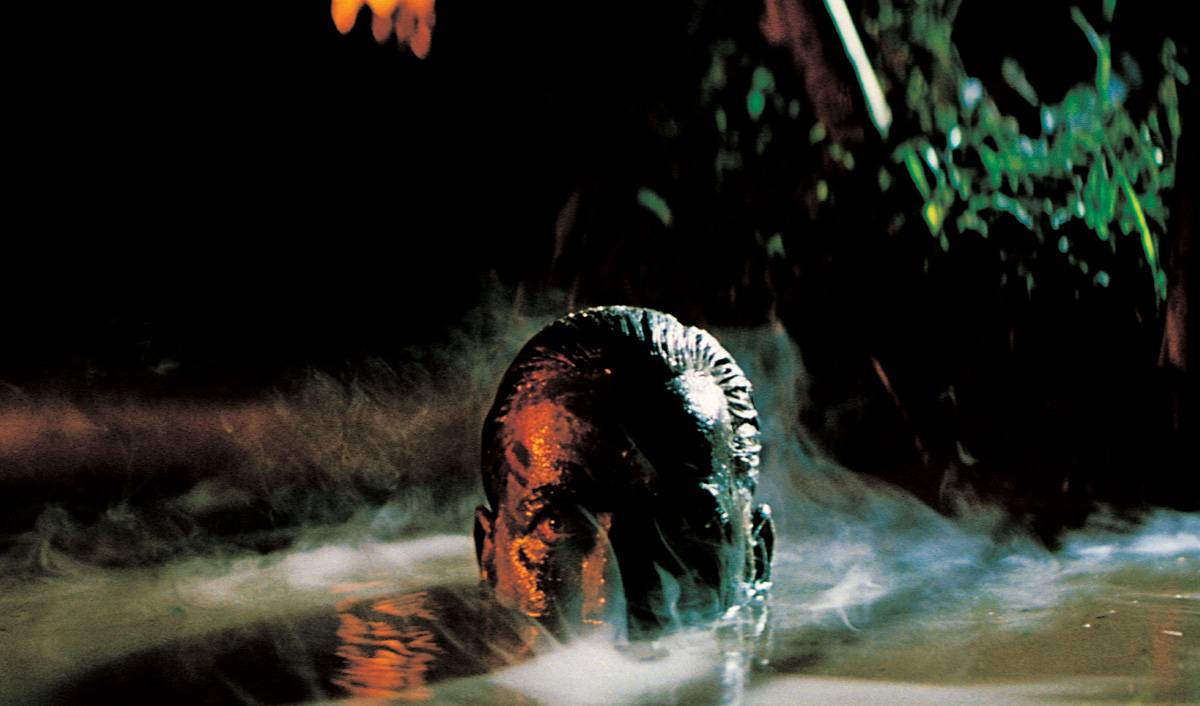

1. Apocalypse Now

Kathryn Bigelow’s “The Hurt Locker” begins with the quote, “The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug.” It could be the tagline for Francis Ford Coppola’s incomparable war masterpiece “Apocalypse Now” as well. Set in the Vietnam War, the film follows a Captain Benjamin Willard who is sent to end the reign of Colonel Water Kurtz who has proclaimed himself as some demi-god inside Cambodia.

Based on Joseph Conrad’s novella “Heart of Darkness”, the film retains and adds to the book’s scathing commentary on the human connection to war, and how deeply personal all aspects of it are, even though the action is shifted from 1800s Congo to Vietnam.

Coppola’s direction is at its most grandiloquent and profound. It realizes the nightmare of the war, but also looks at it from a perspective so dangerously human that you leave scared that even you have begun to love the smell of napalm in the morning. The performances from Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall and especially Martin Sheen are unimpeachable accomplishments that exploit their unique skill sets to the maximum potential.

Coppola proclaiming at the press conference that followed the film’s screening at Cannes that his “film wasn’t about Vietnam, it was Vietnam” might have seemed like an unwise comment at the time. But after more than three decades of its release, it has completely overshadowed everything ever produced or written about the War, and might just end up proving him right.

Author Bio: Anmol Titoria is a student at University and has been writing and engaging in many a parley about film since he was in school, where he was responsible for writing the film column of the monthly newsletter. He professes his love for Kubrick, Bergman and Tarkovsky in ways so multifarious and with such alarming regularity that his family has considered throwing him out repeatedly.