“It is a sad and beautiful world.”

– Roberto (played by Roberto Benigni)

I fought the law and the law won

Incidental encounters and tough luck reluctantly come together in writer-director Jim Jarmusch’s deeply distinctive third feature from 1986, Down By Law. Existing in its own even tempered and hermetically sealed cosmology, joyfully noncommercial and fancy free from the liens of box-office revenue, this is a funny film of unexpected affections, reluctant friendship, and fluky kindred spirits.

By the mid-1980s Ohio-born American indie filmmaker Jarmusch had already established quite a name for himself with his artful low-budget New York City-centric films Permanent Vacation (1980) and Stranger Than Paradise (1984), and the latter’s sojourn to the periphery of Cleveland aside, Down By Law dislocates Jarmusch to the Deep South of New Orleans. But for all of the film’s Louisiana accoutrements––affectionately photographed by Robby Müller’s flush monochrome––this is a film firmly inveterated in the mind of its maker and in what Jarmusch has jovially described as a “neo-beat-noir-comedy.” Laissez les bon temps rouler!

“Down by Law is a movie about cheap whiskey and black coffee, all-night drunks and lost jobs, and the bad times you can have with good-time girls… It’s like a collage made out of objects from old gangster movies, old blues songs and old jailhouse stories.”

– Roger Ebert

In the jailhouse now

Down By Law disentangles on the interconnected lives of an in the stars trio of ne’er-do-wells Jack (John Lurie), a shrewd pimp; Zack (Tom Waits), an unemployed radio DJ known by the on-air persona Lee “Baby” Sims (and who makes a return, in voice only, in Jarmusch’s 1989 omnibus picture Mystery Train); and Bob (Roberto Benigni, in his very first international role), an ill-fated Italian tourist with a loose grasp on the English tongue.

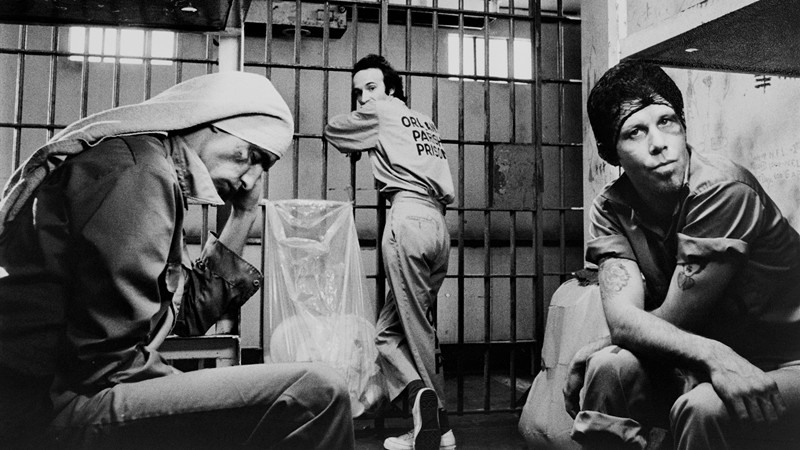

This triumvirate of tough breaks all end up incarcerated at Orleans Parish Prison (known to the locals as “OPP”), with Jack and Zack prize saps, neither having committed the crimes for which they’ve been pinched, and Bob in the clink for committing manslaughter––murder in self-defense.

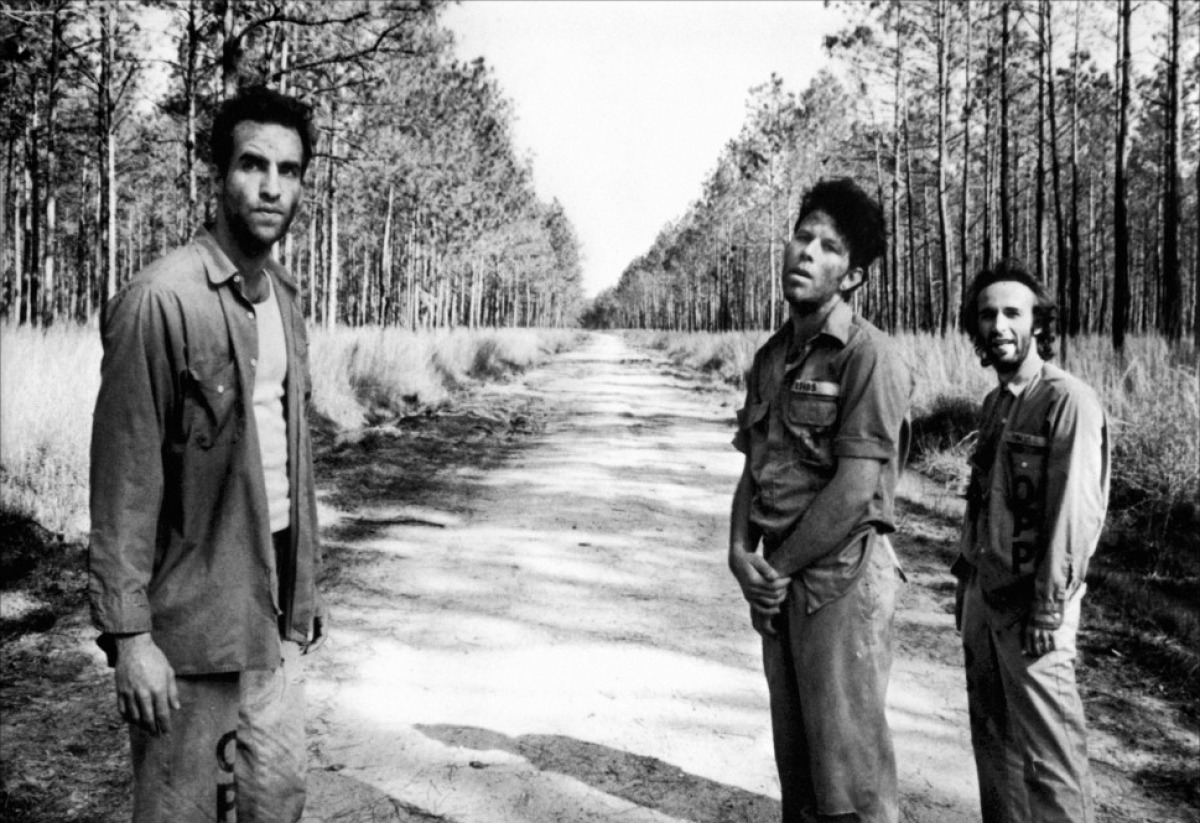

Initially none of the three men seem particularly keen on each other, but as victims of circumstance and shit timing, they each howbeit become buddies. From playing cards and sharing intimacies to rioting over ice cream predilection, these three agreeable offbeat offenders eventually escape into the surprisingly laid-back wilds of backwoods America.

“I always start with characters rather than with a plot… The plot is not of primary importance to me, the characters are.”

– Jim Jarmusch

Do you like Walt Whitman?

As plain and unadorned as the narrative of Down By Law sounds, as ever with Jarmusch, it all seems so deceptively uncomplicated. A filmmaker who’s shorthand and stylistic flourishes always matter more, and who’s glittery surfaces may at first seem surreptitious.

Jarmusch’s love of the long take is on bright display throughout the film, and his detailed and diligent compositions boast much beauty from the silver-tongued symmetry of Müller’s slow-moving black-and-white lensing (this was the first of four excellent collaborations with Jarmusch and Müller; Mystery Train in 1989; Dead Man in 1995; and 1999’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, would follow). Operating with inspired yet tempered mania and crackpot balladry, a largely shapeless plot by degrees that treads and trips into something perceptibly and unmistakably radiant.

“You can throw any number of glosses onto [Down By Law]. It is an open-ended fable that invites interpretations and gleefully defeats them. In this and other ways the movie justifies the cliché label of ‘poetic cinema.’”

– Luc Sante

I ain’t seen the sunshine since, I don’t know when

Ostensibly set in Louisiana, Down By Law exists in a world we clearly recognize yet is clearly and intermittently transcendental. Jarmusch’s Louisiana certainly contains the enunciated architecture of New Orleans and the delicacy of the bayou, but in the same way that Fellini’s Roma is one of vagary and daydreams, so to is Down By Law stirred by artful fabrications and a wondrous sight of farcical occurrence and sometimes cruel comedy.

Some artful deception is viscera for Down By Law, as when our hapless heroes escape the cooler via an underground sewer system, the details of which remain willfully obscured and undefined.

Much of the picaresque scenarios and slips of the film seem to emerge as if through improvisation. Lurie and Waits feel so natural and in-their-element as they joyfully flounder in their Jack-and-Zack schtick. As an unruly third wheel, Roberto Benigni brings a fluky, left of field vibe while continuing the outsider intellection that had been thematic to Jarmusch’s earlier films.

Benigni, already a famous comedian in his native Italy, had been handpicked by Jarmusch to be in Down By Law, with his character––one part fool, one part sage––conceived specifically for him, with many of his personal affectations, ticks, and anecdotal asides worked in (his gut-busting ad-lib monologue on rabbits is factual, as is his notebook of American colloquialisms).

“You always makin’ big plans for tomorrow. You know why? Because you always fuckin’ up today.”

– Bobbie (played by Billie Neal)

Hey little bird, fly away home

Even back in ‘86 there was nothing particularly fashionable or front burner as far as shooting in black-and-white was concerned. Yet Jarmusch’s distinctiveness, style, and sympathies––which could never truly be deemed “commercial”––make for a wonderful resistance to the usual conforming Hollywood ticket.

Down By Law plays it incredibly, impassively cool, and yet somehow ripens into a rapturous and sunny yield. Ultimately, Down By Law plays generously on the psyche and the senses before it all ends rather elegiacally, an imaginative and meaningful American fable.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.