“Chaos is order yet undeciphered” proclaims a confounding yet explicitly authoritative title card at the beginning of Enemy (2013), Québécois filmmaker Denis Villeneuve’s inscrutable adaptation of José Saramago’s 2002 novel “The Double.” It’s a film that’s chilling, sensual, eerie, perhaps at times indulgent, and yet always an artful and audacious affair.

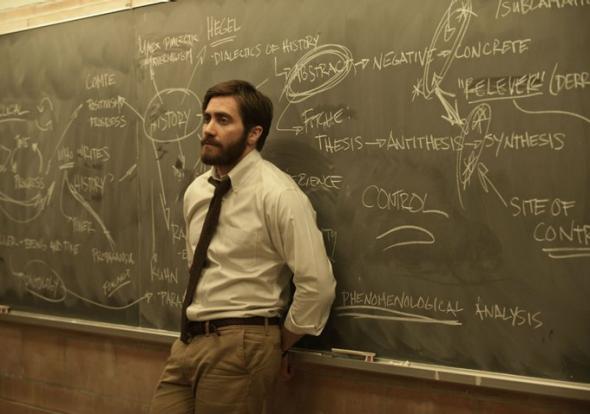

Jake Gyllenhaal, in an understated yet riveting dual performance, is Adam, a history professor in a passionless relationship with Mary (Mélanie Laurent) who soon discovers, after renting a DVD, that an actor in a small role appears to be his doppelgänger. After a little legwork, Adam finds the actor’s talent agency, intercepts some mail and learns his name, Anthony Clair.

As the puzzle-like film unravels, the viewer is treated, amongst other existential horror high jinx, to troubling imagery of spiders, stifled femininity, a tough, washed-out looking Toronto landscape, and increasing dreamlike delusions building to an arresting conclusion and a final shot that is totally terrifying.

Enemy is a resonating work that not only does the Saramago source material a great deal of justice, but presents itself as seductive cinema, sensational at times and quick, guaranteed to pervade the viewer while offering up nightmare fuel and darkly troubling fantasy.

7. A complex thrill for fans of puzzle movies

For audiences who enjoy a certain intricacy in their cinema, with stories that become dangerous, evolving, and feature shocking surprises and startling revelations, then Enemy is high-grade catnip.

Deciphering puzzle films such as John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966), Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995), David Fincher’s The Game (1997), or Fight Club (1999), and particularly the works of Christopher Nolan (namely 2000’s Memento or 2010’s Inception), or David Lynch (2001’s Mulholland Drive and 2006’s Inland Empire being his best most recent examples) can be a very gratifying and rewarding in ways that so many films simply are not.

The movies listed above, like Enemy, belong to a category of enigmatic films that have legs, that will follow the viewer for hours and days afterwards, often demanding to be rewatched, reconsidered, and enthusiastically recommended.

While it’s true that Villeneuve’s Enemy seems to display an almost hostile disdain for storytelling conventions and a brazen refusal to renounce its secrets, it offers ample evidence and sly suggestions to what is unraveling in the unreliable eyes of the protagonist.

One clue, and this is truly just a mild spoiler, can be found in the personalities of Adam and Anthony, both played by Gyllenhaal. These two display very few discernible differences, they’re both reserved men, and it’s not surprising that there’s identity confusion between them and the viewer.

This is most astonishing and underscored when Adam visits his mother (Isabella Rossellini) who makes a rather derisive reference to his acting career. Is it not Anthony who’s the actor? Suddenly the audience is right there with Adam wondering who’s who?

6. Surreal in a way that David Lynch fans will appreciate

While it has been established that Enemy is a gratifying puzzle picture à la Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire, there’s other evidence that Villeneuve was taking considerable cues from the David Lynch playbook. The wonderful presence of Isabella Rossellini as Adam’s mother conjures her unforgettable role as the tortured matriarch/lounge singer Dorothy Vallens in Blue Velvet (1986), and perhaps to a lesser extent, her troubling turn as Perdita Durango in Wild at Heart (1990).

Gyllenhaal’s Adam/Anthony protagonist is a self-dividing doppelgänger, not unlike the characters trapped by circumstance in Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Dr. (2003), and the Twin Peaks cosmology, too.

Lynch’s signature idle pacing seems to marvellously haunt the canter of many scenes, certainly a deliberate pastiche when you consider the Silencio-like fetish club (absent from the Saramago novel) that introduces the film.

None of this is to suggest that Villeneuve is plagiarizing anything from Lynch (who himself often makes allusions to the works of Kenneth Anger, Luis Buñuel, and Jacques Rivette mingled in with his own distinct ontology), but he casts a big shadow and often uses universal archetypes. Villeneuve is an original, absolutely, but he’s not above influence and assistance from past and present masters like Lynch.

5. Jake Gyllenhaal’s strong performances

In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter during the press junket for Enemy, Villeneuve enthusiastically stated: “I knew that the movie would work and it would make sense … only if I had a very strong actor in front of the camera… I was in need of a creative relationship as a director. I really needed to create a relationship with one actor to think about acting, directing and filmmaking together, and I think Jake had the same need. I think he did Enemy not that much because of the screenplay but because of that process I wanted to do, which was to share cinema with him, to exchange, to have the chance to take time and to risk and explore things in front of the camera.”

With Enemy, Gyllenhaal’s daunting task involved portraying the most subtle of differences between two men whose identities are oscillating wildly. It’s a nuanced performance, and as Adam/Anthony slide into irrational, unknowable, and inexplicable depths, the audience is with him, utterly convinced, every hungry step of the way.

4. Striking cinematography

Villeneuve had previously worked with Enemy’s cinematographer Nicolas Bolduc on the award-winning 2008 short film Next Floor and to reteam on a larger and more ambitious project seemed a logical next step when the opportunity arrived. And Bolduc expert lensing suits Villeneuve’s vision perfectly.

Shot and set in Toronto, Canada’s largest city is transformed into a tough, washed-out metropolitan landscape of jaundiced skies, sweeping glass cylinders, cold chrome and concrete, where spidery figures loom in the haze and shadows. It’s a hypnogogic and desolate outlook for a desolate and dream-like film.

3. A fascinating tangle of psychological horror and sex farce

Enemy doesn’t clearly belong to any one specific genre but it certainly has elements of kinky sex absurdity and the emotional anguish of a frightening mindfuck.

Without getting spoilery, let’s just say that a recurrent arachnid-motif frequents the film from the beginning of the movie to the final frames. The spider’s symbolic connotations can be looked at from a number of ways, but they all come back to horror imagery. In Japanese folklore there is the Jorogumo (a human-appearing seductress that can transform into a spider) for instance, and Adam has a nightmare of just such a creature. Anthony’s motorcycle helmet has an insect-like visage that shines like Adam’s bad dreams. The startling similarity is intentional.

A gossamer web-like appearance of a cracked windshield after a climactic crash is especially chilling, and the most effective apocalyptic visions in the film (particularly the unforgettable jaw-dropping ending) all work with the spider subject. Enemy is an arachnophobe’s worst case scenario writ large.

In keeping with Saramago’s novel (the spider stuff is absent, also) are the many subtle and not so subtle sex farce elements. There’s a fair bit of devilish fun as Adam/Anthony conceal their switched identities and swap lovers. It’s been suggested, and there’s ample proof to believe it, that Enemy is a story of infidelity and guilt, and that maybe Gyllenhaal’s identify crisis is a result of cheating on his pregnant wife Helen (Sarah Gadon) with Mary (Mélanie Laurent) and having burning remorse.

2. Enemy takes a challenging novel and imaginatively reinterprets it

Enemy is a polarizing film, due largely to the enigmatic upsets that can cloud some of the meaning for the audience. Saramago’s Portuguese source novel “The Double” (2002) is likewise polarizing, and also very intense and dactylic but lacks both the spider motifs as well as the themes of totalitarianism (Adam, a university professor, lectures on this subject and elements from his lecture recur throughout the film) present in the movie.

Villeneuve’s film, assisted by screenwriter Javier Gullón, and Saramago’s novel, diverge in other areas, too, but where the director is most faithful to the author’s work is that both stories share existential horror, unbridled libido, a cruel comedy of both errors and manners, and the questionable duality of the protagonist.

Dry humor and tangible dread are in both works of art, and while both end very differently, they assign an unnerving resolution that has the audience/reader contemplating our perception of the characters. Identity remains ambiguous and open to interpretation in both works, and therein lays their connection.

1. In Denis Villeneuve’s own words

“You don’t know if they are two in reality, or maybe from a subconscious point of view, there’s just one. It’s maybe two sides of the same persona … or a fantastic event where you see another [self].”

“I thought that in the book … it was so strong … the strangeness and the monstrosity of such an encounter: meeting someone that looks exactly like yourself. There is something unbearable about it. And in order to create that, I needed both characters to be physically identical but … have different souls.”

“How can we evolve and not repeat the same mistakes that we are doing over and over again? That’s why [Enemy] is constructed like a spiral. That’s why it’s a challenge for the audience, it’s an enigma, but I hope that the audience will have fun trying to solve this enigma.” –– Denis Villeneuve

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.