“Therefore, in this pain lies a spark of hope. I trust you will see it and nurture it”

– Thomas Moore on the experience of heartbreak

Extreme Spoiler Alert! As one might guess from the title of this list, it will examine in detail a variety of heartbreaking things that transpire during Logan’s 141 minutes.

With the release of each new superhero movie, it is common to see the superlative phrase “Best superhero movie ever!” A number of factors go into making a truly great superhero movie, and there have been many great superhero movies over the years. In the present case of the movie Logan—released on March 3, 2017—we see something new, however: a devastatingly sad superhero movie.

To truly appreciate all the nuances of sadness in writer/director James Mangold’s film, it helps to have some general knowledge regarding the X-Men mythology, but one of the amazing things about the film is that it does a very solid job of being a stand-alone piece on the nature of heroism. It is, even more broadly, a sprawling meditation on good versus evil as an ongoing process, rather than as an end goal.

This is, in fact, the key to the idea Logan reveals for us as it unspools: good versus evil is an ongoing process that will lead us eventually to seeing all of our heroes die. Very likely they will die horrible deaths. As spectacular and impressive as their lives may be, their deaths will be ugly, and only impressive in degree of horror.

In the aftermath of the horror of witnessing our heroes dying before our very eyes, we will further be forced into the choice of following in their footsteps. Our heroes may be large-scale public figures, or they be as relatively small-scale as our parents. Or, as in the present case, they may even be both. Logan is the rare big budget Hollywood picture—marketed as entertainment—that invites viewers to see the darkness and the pain of heroism as well as the light of hope that shines in it.

As Jungian psychologist and therapist Ginette Paris writes, “The pain of heartbreak and mourning is truly a push from nature, to propel all of us beyond our contemporary dysfunctional myths about love, freedom and relationships. No one volunteers for a devastating heartbreak, yet, it happens! Those who succeed in liberating their captive heart gain an advantage over others, because they learn, at great cost, what supports love and what doesn’t.”

We can certainly think of what we feel for superheroes as a kind of love, and it is the pain of feeling this love shatter that we feel in Logan as events go from bad to worse, and as even victories are either Pyrrhic (come at terrible cost) or incomplete.

1. The two main superheroes in Logan die

They don’t die spectacularly or gloriously. They die horribly. The lead-up to their deaths is long and made very clear throughout the film. When their deaths come, it is only surprising because it is hard to believe a Hollywood studio would allow them to die—not because either of them were doing so great up until the moment of their death. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Both Logan and Professor Charles Xavier look and sound terrible throughout most of the movie. Hugh Jackman’s muscular body is a huge mass of scars and, increasingly, even partially healed open wounds. As Wolverine, his adamantium laced skeleton may be indestructible, but his healing powers are slowed—apparently by the inherent toxicity of having a metal-infused body.

To metaphorically push this out of superhero mythology and into reality with which viewers can identify, parallels are repeatedly drawn between Logan’s symptoms and those of advanced lung cancer. Patrick Stewart (at only 76 years of age) is made to look extremely decrepit and wasted as Charles, now in his 90s.

It is also implied that Charles is either in the early stages of Alzheimers or ALS. Again, this roots some of the film’s most visually spectacular sequences—Professor X’s seizures which paralyze hundreds of people and violently shake reality itself—in sadly common degenerative diseases associated with aging.

Finally, in case the grim reality of superheroes aging toward death was not drawn with sufficient clarity, both Logan and Professor X are now totally reliant on medication to even function at all. Logan spends much of the film self-medicating his pain with a steady stream of alcohol (which, notably, results in absolutely zero comic relief of any kind), and is ultimately only able to maintain his heroic mutant powers with the aid of injections.

In Charles’s case, he requires a continuous stream of capsules and injections to keep his powers from unleashing catastrophe. A phrase that comes to mind throughout much of the film is the Biblical “How the mighty have fallen.”

2. The female lead is a pre-teen girl who kills many people with extreme viciousness

Laura (also known by her experimental label “X-23” and played by Dafne Keen) is ambiguously somewhere around 12 years old. The choice to focus on her character at this young age was clearly made to maximize the impact of her loss of innocence, and Keen’s excellent performance in the role is well-directed to retain a balancing (and heartbreaking) measure of that innocence.

In expository flashback we see the tortuous procedure whereby Laura’s skeleton was laced with adamantium. Immediately following we see an image of her engaging in the psychopathology known as “cutting” or “self-harm” which is sadly not uncommon among young people. In Laura’s case, of course, because she has mutant healing abilities the cuts heal instantly.

Yet this fact serves here to drive the wrenching loss of innocence in more deeply as we watch her cutting and healing over and over again as she cowers in a corner of the lab where she is captive.

It is unsurprising, then, once she has escaped her captors, that when they send their enforcers (the cybernetically enhanced “Reavers”) to recapture her, she puts up a deadly fight. And yet each of her fight scenes is carefully choreographed and performed to minimize the element of entertainment value so common in many action films.

There are no comic one liners to break the tension as Laura’s only utterances are feral growls and screams. There are no vogueing martial arts poses. Even wire-and-harness-enhanced choreography is kept to a minimum to maintain the harsh filmic reality of a pre-teen mutant bloodily stabbing and chopping black-garbed super soldiers to pieces to protect herself.

3. The other young people in Laura’s experimental group are, unsurprisingly, treated badly too

At its heart this mistreatment consists of dehumanization. When Donald Pierce (Boyd Holbrook), the leader of the Reavers, first mentions Laura, he refers to her as a thing—not only a thing, but “something of mine.”

A thing among many things that belong to him and his employer, the genetic research multinational Transigen. Further on, the conditions of the young people’s creation and captivity in Transigen’s Mexico City lab (their work, we are told, would be illegal in the US or Canada) are described in thankfully brief, yet still awful detail.

Then finally we see a spark of hope: a birthday party for the young people in the lab, thrown for them by their nurses. Yet even this is broken up by the Reavers specifically because the children’s scientist creators do not want them to be humanized. Then immediately after comes the announcement that all the young people are to be scrapped in favor of more successful experimental creatures.

4. The bad guys outnumber the good by a truly outrageous ratio

Within the context of the story this outrageous ratio is also completely believable because it is framed within a “David versus Goliath” context. Even structurally the villains here have extraordinary advantages. The film’s main villains are three in number. In addition to Donald Pierce, there is also Dr. Zander Rice Jr. (son of Wolverine’s villainous creator, and head of the Mexico City lab experimentation) as well as the mutant known only as “X-24” who appears to be a soulless clone of Logan.

However, while the main heroes and the main villains are equal in number, the villains control virtually all the resources we see in the film from the seemingly endless army of Reavers, to vehicles and weaponry, to medical supplies and facilities, to even the farmland and food supply (see point 5 below).

At a kind of ideological level, this diffusion of villainy in the film also works to keep viewer satisfaction to a minimum when the villains are defeated. At every turn, the film assures us that there will always be more bad guys coming.

By resisting the elevation of a single super villain to primacy within the narrative, the film also resists the bolstering of the so-called “great man of history” theory seen in so many “good versus evil” stories. Here we are robbed of the catharsis of cheering for the final defeat of the single super villain. Instead we are left with the sense that the system of villainy spreads far beyond any single villain or group of villains.

Because villainy itself is shown to be diffuse, so too must heroism be. The black and white line between winning and losing is blurred into a contingent and even depressing spectrum of gray shading between the possibility of light, and the certainty of returning darkness.

5. The film’s major subplot of large corporations using their resources to abuse less powerful individuals or groups

As Logan, Charles and Laura are driving cross country to get to their potentially nonexistent destination on the northern border of North Dakota—where Laura hopes to join the other young mutants escaped from Transigen and find asylum in Canada—a fascinating and deeply unsettling subplot emerges.

Both our trio of heroes and an African American family of three (Will and Kathryn Munson and their son Nate played by Eriq La Salle, Elise Neal and Quincy Fouse respectively) carrying several horses in a trailer are run off the road by a shocking pack of driverless “auto-trucks” (Logan refers to them as “damn auto-trucks,” implying that they may cause such problems routinely.)

The trucks belong to a company called “Canewood Beverage International” which has been trying to buy the farmland belonging to the Munson family. After Charles uses his telepathic powers to gently return the spooked horses to their trailer, the family brings them back their farm for a meal and a good night’s rest.

What appears to be a narrative tangent rapidly circles back to instead tie the mythological superhero thread to its mirror image in a reality-based subplot that once again features a rapacious multinational corporation (and, in fact, one that appears to be a subsidiary of Transigen). In this case Canewood Beverage is producing massive quantities of genetically engineered corn for the high fructose corn syrup it yields to sweeten processed beverages and foods.

The nasty products produced by Canewood are juxtaposed with the wholesome family meal that Kathryn cooks (and Laura devours barehanded in a rare moment of comic relief). The horror of Canewood’s faceless corporate culture (introduced by the auto-trucks) and its redneck human enforcers is juxtaposed with the home the Munsons have created that Charles describes to Logan thusly, “This is what life looks like: a home, safe place, people who love each other. You should take a moment and feel it.”

Of course this fleetingly idyllic safe place is soon wracked by a battle with the Reavers—including the Logan clone known only as X-24—that results in the deaths of Charles as well as all of the Munsons. Will, the last to die, even pointedly attempts to blast Logan with his shotgun only to find his ammo spent.

There is no safety here, and the African American casting of the Munson family gestures toward a grim portrait of how non-whites fare within American society. This grim portrait is extended, of course, to Latinos through the inclusion of the Mexico City lab and nurse Gabriela (Elizabeth Rodriguez), who attempts to save Laura and is murdered earlier in the film for her kindness.

6. References to other heartbreaking and uniquely American works of art

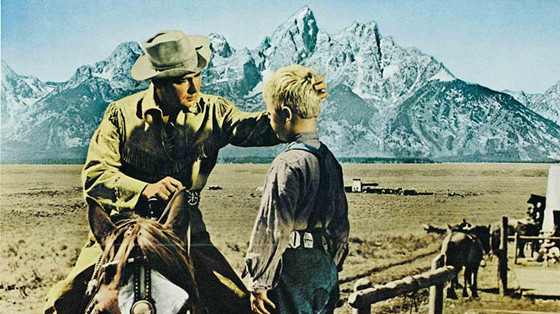

Logan extensively refers to the 1953 Western film Shane, one of the saddest Westerns ever made. In that earlier classic film Shane (Alan Ladd) rides into a pioneer farm and becomes embroiled in a conflict between powerful ranchers and small farming families. In Logan, Shane is referred to twice. First as Charles and Laura watch the film in their Oklahoma City casino hotel, and then again later when Laura quotes some of its most memorable lines as a eulogy for her father Logan.

The lines in the film are spoken by Shane himself as he rides away (possibly fatally injured) from the farm at the film’s end: “A man has to be what he is, Joey. Can’t break the mold. I tried it and it didn’t work for me. Joey, there’s no living with a killing. There’s no going back from one. Right or wrong, it’s a brand. A brand sticks. There’s no going back. Now you run on home to your mother, and tell her… tell her everything’s all right and there aren’t any more guns in the valley.”

Such extensive and detailed quoting clarifies the filmmaker’s intentions to tie Logan to the history of American cinematic depictions of heroism. Further, the specific choice of Shane—an old film that refers to an even older period in US history—ties Logan precisely to ideas about the conflicts that inhere in the so-called “American Experiment.”

Conflicts between individual rights and the powers of government or other large institutions. Conflicts that arise because power can—and does—corrupt. Conflicts that must be cyclically renegotiated, and are always only temporarily resolved until the next heartbreaking abuse of power occurs and must again be struck down by some kind of hero.

Finally, the background song for the film’s full length trailer was Johnny Cash covering the 1994 Nine Inch Nails song “Hurt.” Its lyrics begin, “I hurt myself today / To see if I still feel / I focus on the pain / The only thing that’s real.” The complex intergenerational influence of Johnny Cash’s poetry of hope and despair upon American storytellers rings out again in the feature itself, which ends with Cash’s own original 2002 song “The Man Comes Around.”

This song describes a Biblical armageddon, and begins with the lines, “There’s a man going ‘round takin’ names / And he decides who to free and who to blame / Everybody won’t be treated all the same.”

It forms a powerful punctuation mark at the end of a powerful meditation on the never ending cycle of heartbreak and struggle for healing.

Author Bio: Jim has been a projectionist for over 25 years at the University of Michigan, where he earned his degree in film studies. He has long studied how formal aesthetics affect the creation of potentially life-changing meaning in art forms from film to architecture. He has presented multimedia lectures on anime, and composes experimental electronic music as The Fleshy Timeclock.