14. Munyurangabo (dir. Lee Isaac Chung)

A simple film about two boys living in the shadow of the Rwandan genocide, Chung mirrors other great social realist films. Taking real world people, working with an amateur crew and shooting on a low budget proves that one only needs a passion for greatness.

Why it is essential: It is difficult to recall any other major films that honestly tackle the ramifications of the Rwandan genocide on both the Hutus and the Tutsis. Treating each side as people put into a bad spot by rich aristocrats. It is also notable that Chung was merely volunteering as a teacher wanting to teach his students practical filmmaking. The amateur flare works in “Munyurangabo’s” favor.

15. All About Lily Chou-Chou (dir. Shunji Iwai)

The structure of this film is nonlinear and the formalist approach to the narrative resembles Wong Kar-Wai’s cinematic stylizations. “All About Lily Chou-Chou” has an invigorating dreamlike aesthetic that compliments not only the protagonist’s mental health, but acts as a visual recreation of Chou-Chou.

Iwai’s coming of age film explores the lives of two pubescent boys in Japan, Hoshino and Hasumi, they listen to an experimental singer named Lily Chou-Chou—her music resembles Björk. Spending much of their free time on a messaging board discussing her work. However, after a near death experience, Hoshino becomes a bully, abusing his classmates and being an all around antagonist to everyone around him.

Why it is essential: Iwai was one of the earliest adopters of the digital camera known as “24 progressive,” and the film is shot remarkably. Taking what could be a limitation and making the most of the new technology. The photography’s kineticism is a sight to behold.

16. Ten (dir. Abbas Kiarostami)

Here, Kiarostami utilizes the car as his primary location. Previously he used cars as vehicles for location changes with many of the exposition or character development being relayed there. But in “Ten” he the camera is placed inside of a woman’s taxi as she drives around Tehran having conversations with a multitude of people.

Why it is essential: “Ten” addresses problems in Iranian society two years after “The Circle.” Although this film was not banned, it is still an insightful look at contemporary discrepancies in Iranian life, especially for women.

The driver (Mania Akbari) is going through her own divorce from her husband, this leads to conflict among her and her son (played by the actress’ real son) over the domestic issue. The arguments presented by her son are indicative of how cultural gender inequities are passed down from generation to generation.

17. Taxidermia (dir. György Pálfi)

A surreal black comedy about three generations of men with some sort of exaggerated obsession. The first is a sexually frustrated soldier who mistakes fantasies for reality. He thinks he has sex with the lieutenant’s wife but awakens to a slaughtered pig he inadvertently impregnates, however the lieutenant stumbles upon the scene and executes the soldier.

The lieutenant raises the baby as his own and in the second story we see this baby grow up into a competitive speed eater. He elopes with a fellow speed eater and they bore a child together. This boy grows up to be thinly and sick compared to his obese father and his obsession is taxidermy.

Why it is essential: Apart from the surprisingly sumptuous photography, these three men are supposed to be an allegory on Hungary’s history in the 20th century. What they represent for Hungary is not clear, but what is clear is that the humor is grotesque and blunt. The comedy rivals Takashi Miike’s twisted sense of humor.

18. Oasis (dir. Lee Chang-Dong)

A truly unique take on the romantic melodrama. A mentally disabled man, Hong Jong-du, is released from prison after serving a sentence for a hit-and-run. Jong-Du meets the sister of the family he is trying to reconcile with, Gong-Ju, but she has severe cerebral palsy. Living in a world where no one wants to acknowledge their existence, Jong-Du and Gong-Ju become inseparable, confining in their mutual alienation.

Why it is essential: Maybe one of the most enduring films on love deemed inappropriate by the same people who neglect them. “Oasis” makes the case that love is truly blind. Not only that but the film asserts the old mantra that opposites attract. Though they are both disabled in some capacity, Jong-Du is mentally slow, while Gong-Ju is physically impaired, but this difference is irrelevant in the grand scheme of things.

19. Turtles Can Fly (dir. Bahman Ghobadi)

A lord of the flies-like scenario where a group kids must work together to survive, “Turtles Can Fly” is the story of a Kurdish refugee camp during the invasion of Iraq. The film’s central character is a thirteen year old boy named Satellite who leads a group of children to clear land mines, and selling the undetonated ones. But Satellite becomes infatuated with an orphan named Agrin and revelations of her brutal past answer many questions.

Why it is essential: Filmmakers have been attempting to capture conflicts in their infancy with as much verisimilitude as possible for decades. Ghobadi does that here, but instead of showing any imagery of combat, he focuses his camera on the lives of refugees awaiting the arrival of the US military. And it is the first film made in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein.

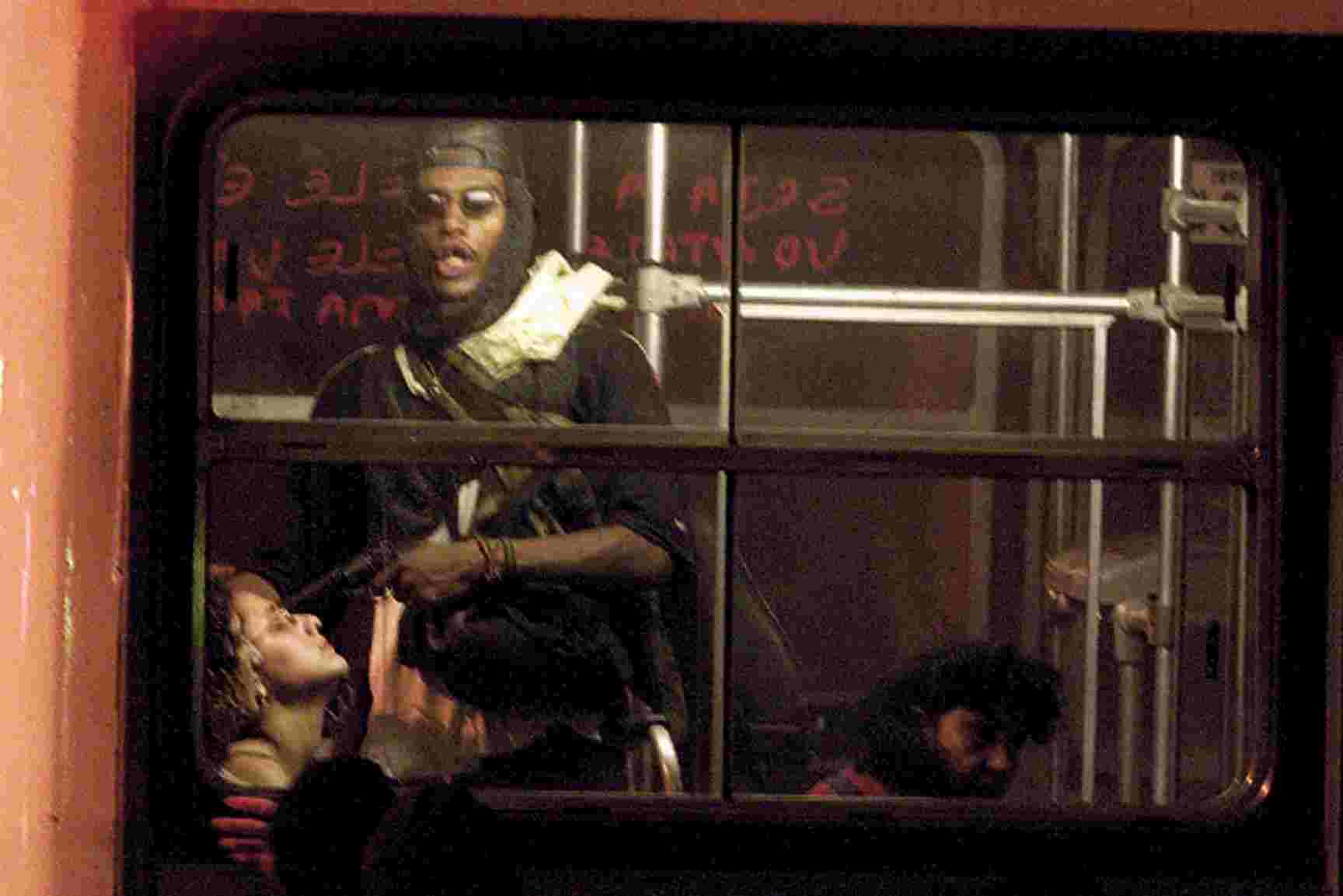

20. Bus 174 (dir. José Padilha & Felipe Lacerda)

Many people may point to “City of God” as a decent landmark in crime films from Brazil. However “Pixote” and this are probably a more nuanced look at blue collar crime in the favelas of Brazil, as “City of God” tells a once in a lifetime story of revenge and double-crossing. However, “Bus 174” examines an ordinary poor kid’s life, Nascimento, analyzing his situation before he hijacked a local bus at gunpoint.

Why it is essential: “Bus 174” aims to criticize the weakness in Rio De Janeiro’s law enforcement, and putting a spotlight on the criminal justice system, as well. The film attempts gain insight onto why Nascimento went to such an extreme.

One knows too well that hijacking a bus would not bear much fruit as the people riding it are probably low class, too. However, it is clear that Nascimento’s hijacking was a cry for help knowing that there was probably no way to express his frustration he snapped and went to a point of no return.

Author Bio: Dajoune Rogers is a college student in Sacremento, California majoring in Film. He spends most of his free time reading and watching at least 3 films a day. He has an active a micro-blog on Instagram, @film_literacy.