6. Goodbye to Language (Jean Luc Godard, 2014)

Here is another rebel, one that has been a rebel since the 60s, when Maoism and Marxism were all the rage in academic and new left discourses. These concepts are still alive and evident in politically and ideologically charged films in the 2010s, with the same revolutionary attitude and power.

The desire to experiment with avant-garde filmmaking has been limited to ludic postmodernism, with products destined to a niche of very selected consumers and therefore diminished social power, so this effort by Godard is extremely valuable because it escapes the confines of the exclusive cinematic circles by virtue of the director’s fame.

The film itself is a tribute to the power to break all rules, something that digital cinema has the power and the obligation to do. Godard creates a collage of sensations toward a purely experiential cinema that also utilizes 3D as a medium through which the audience is confused, alienated, and at the same time, woken up by an endless dream.

This is the burden of representation, the servitude to a certain type of codification of the cinematic image that has been put in place since the late 70s and from which, according to Godard, cinema has never fully recovered.

Godard uses digital and the power of digital 3D to venture again into a world where everything is possible, and celebrates the death of cinema, while at the same time celebrating its continuation toward new heights.

7. Flora Petrinsularis (Jean Louis Boissier, 1994)

Is this cinema? It is probably more of a conceptual art piece or a video art installation, or maybe it is cinema, which takes the implied participation of the spectator in the digital reprogramming of cinema and does something playful and self-reflective with it.

The film takes the concept of the loop, which has been explored by the Russian filmmakers of the 20s (Vertov used the loop to create a narrative), and deconstructs the idea to create the lack of a narrative. In fact, the way in which who is experiencing the artwork approaches the two looping images that the film proposes do not create a narrative but another inescapable loop.

Jean Louis Boissier tries to reshape the temporal dimension of cinema, and in particular digital cinema, by creating a film that does not play forward, does not play backward, but is looped. “As digital media replaces photography and film, it is only natural that the computer looping program should replace photography’s frozen moment and cinema’s linear narrative.”

These are words from the “The Databank of the Everyday”. The endless spiral of looping images is also a metaphor for the endless search for truth and desires of humanity.

8. Mirrored Mind (Sogo Ishii, 2005)

The film was shot as part of the project “Digital Short Films by Three Filmmakers”, an initiative by the Jeonju International Film Festival. This film will not be one that makes an appearance in every theoretical book about cinema, but it’s an important film.

The director was famous for his punk filmmaking, and people suggested that he abandoned his roots for this film, but this is not at all true, as he uses the power of the digital to get literally close to the skin of the characters. It is skin-to-skin filmmaking of the highest level, with the power, at times, of the cinema of Sion Sono.

With a digital coldness, he depicts the urban alienation of Japan with touches of the great Tsai Ming Liang, and when he inserts moments of beauty and poetic landscapes, he does it with a scintillating coldness and an unreal sparkle that brings to mind ideas of commodification of the East by its own pop culture and by the West’s pop culture.

The most evoking image is probably the one in which the protagonist swims in the swimming pool, in a natural paradise with inverted polarity, where the sky and the swimming pool mesh together like two amniotic fluids, and the nature fragments in rivers of cold light blue and green, like a pre-code vaporwave artwork.

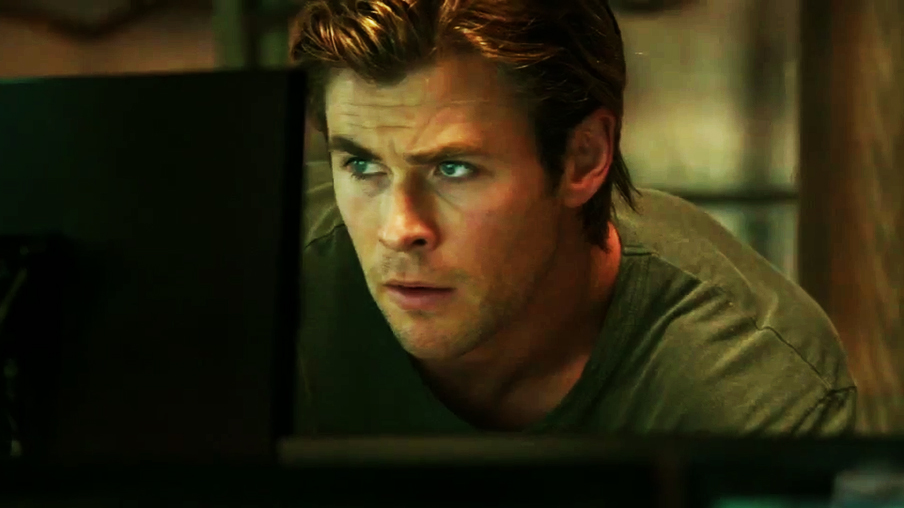

9. Blackhat (Michael Mann, 2015)

Some critic, probably in a slightly overdramatic way, described “Blackhat” as the first film of the digital age, joining the group of people supporting the film in the midst of its critical and economic meltdown in American and European theatres.

The film was a failure, but it is one of the very best films produced by Hollywood and the American film industry in the last five years, and its failure has to be connected not to a lack of quality, but to the presence and the implementation of avant-garde topics and cinematic techniques.

This is especially related to the use of digital cinematography and camerawork, as well as the overarching thematic concerns of the film, with the digitalization of society, the relationship of the body with capitalism and with the digital world, which is its own abstraction, in a way that was challenging enough that it puzzled the audience.

Using the word “masterpiece” to describe “Blackhat” would not be out of place, and it is certainly a cult film for a specific fringe of the film universe. The film is a cyberpunk story with influxes from Pynchon, Gibson, and other greats.

Michael Mann uses saturation to camouflage digital shots of surveillance cameras and make them look like something else, and invades the screen with anti-naturalistic tones of blue that give the idea of the disappearance of the body, of a melding between the software and the physical reality, a human that is turning into fluid code.

This idea of fluidity is clearly at the center of the film, as it is at the center of speculative thought in the last 20 years of sociology and philosophy, from Baudrillard, to Bauman, to Pynchon, to Nick Land.

The phosphorescent deep blue of the film does not degenerate into “Tron: Legacy” territory, because Mann uses handheld cameras and other techniques in a way that emphasizes the heaviness, the fatigue, and in a way the tiredness of the body in the digital era, a body that feels like it’s collapsing, evanescent.

Mann dives into a river of data with the camera in the very first moments of the film, and emerges from it with a physical disaster that poisons the physical world. The digital is not isolated and uplifting, as it was in films like “Tron: Legacy” or other late century films, and it is not demonic and alienating like it was in the sci-fi of the 60s.

The digital aesthetic and the visual sensibility of “Blackhat” travels on the thin line between reality and representation, between a body and the cluster of data that implies, deconstructs, and reconstructs the body. It is a crime film that is shot like a ghost story, a cyber-thriller that is also an on the digital image and its contradictions, a ghost story about the ghosts of capitalism and the ghosts of technology, about abstraction and concreteness.

Cinematically, it is a film in which the camera and the image enter a realm of post-truth, where it represents reality, and is at the same time the undoing of that same reality, as it films that moment of material collapse when something becomes something else, and it captures the transformative nature of the digital. “Blackhat” is a great film.

10. Gummo (Harmony Korine, 1997)

Harmony Korine was a digital hurricane unleashed on American cinema. Opinions are pretty much divided on him; he has really strong admirers (Herzog, above all) and many haters.

Post-cinema and digital cinema are all intellectual superstructures that probably don’t describe the cinema of Korine effectively; it is a mixture of Herzog’s brutal dreaminess and the Dogma’s digital honesty, with a touch of psychotic Americana and nods to postmodernism and pop culture.

“Gummo” is visually imposing because it avoids the idea of the clean digital image, the image that is sensual, immobile, sparkling, advertising, and brings the digital back to its original grainy palette. The power of the digital is to somehow bring an element of found footage, of randomness to the cinematic image.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.