6. Talking Head (1992)

“The audience, having escalated their desire to watch is now reaching the point of apathy. No matter what or how you show it to them, it won’t amount to much.”

Well, in this case, “what” and “how” do amount to very much. Talking Head is a wordy, yet never boring meta film about film, anime and the history of cinema – as viewed through the prism of the author’s personal interpretations and tribulations. Beautifully shot by Yōsuke Mamiya who worked on both the previous and next list entry as well, it offers the experience vastly different from any other movie (within the movie).

Its ironic, self-referential story revolves around the disappearance of an esteemed director, Rei Maruwa (guess whose pseudonym this is), during the production of his latest feature titled Talking Head. A “ghost director” who’s able to mimic any of his colleagues’ style is called by a producer faced with a fast-approaching deadline. Once he arrives at the studio, the eccentric crew members (named after Oshii’s collaborators) start to die one by one in the oddest of ways.

As avant-garde and genre-defying/defining as it gets, this pseudo-mystery develops at a rapid-fire pace in spite of its many “static” moments and deliberately stagey sets. Given its nature, it is no surprise that the parody of product placement and the reference to Georges Méliès – between the lines filled with the motley crew mishaps (bizarre incidents involving dismemberment and a giant mushroom, inter alia) – seem so apt and true to the film’s mind-bending reality.

Mixed with off-kilter humor and presented in a series of meticulously composed tableaux vivants of soft reddish lighting and the jazzy soundtrack, Oshii’s serious ideas and lengthy dialogues are much easier to digest. And a Lynchian singing scene is the most welcomed breather.

5. The Red Spectacles (1987)

“Man is neither an angel nor a beast. However, unfortunately, while he wishes to act like an angel, he actually behaves like a beast.”

During the very first minutes of The Red Spectacles (Jigoku no banken: akai megane), Kerberos corps are described as “the Anti Vicious Crime Heavily Armored Mobile Special Investigations Unit” in what is supposed to be an excerpt from a fictitious book The Complete History of the Criminal Law Enforcement Organization by Hyohe Shiozawa.

But, nothing in the intentionally convoluted text can prepare you for the hysterical mélange of odd drama, Godardian sci-fi, absurd spy thriller, pinches of comically violent action, and slapstick antics that mimic/parody anime humor – all in a dystopian setting of illegal stand-and-eat soba shops and from the distorted perspective of an ex-officer, Koichi.

Four years after this outré Shakespeare-and-Pushkin-quoting extravaganza, Oshii will rewrite his alternate history for Stray Dog which makes the Kerberos diptych and surrounding mythology even more baffling (not to mention the involvement of Moongaze Ginji).

The Red Spectacles starts off where the sequel-prequel ended, with Koichi returning from exile to search for his old friends. However, his quest quickly turns into a dream within a twisted reality within a dream of a woman whose face appears everywhere throughout the city – on posters, billboards, silver screen and old photographs.

Who is she? Why does she reappear in Talking Head? What hides behind her enigmatic smile? Is she, perhaps, a personification of the very movie? The unattainable ideal? Oshii refuses to answer, yet his obscurantism is inspiring.

In “Neo-Alphaville” of Koichi’s delusions no one is to be trusted, especially when the events are peeped on from the hole in the fourth wall. But, both the tinted B&W cinematography (with some splashes of color) and unpredictable soundscapes make for quite an enjoyable illusion.

4. The Sky Crawlers (2008)

The skies are their everything – a mother and a father, love and hate, life and death. And they are the “Kildren” – eternally young pilot/killer-children created to operate fighter planes and wage an endless war for the amusement of adults who lead a “normal life” in bogus peace.

Their world – reminiscent of Europe from the WWII period and run by big, shady corporations – is conceived by Hiroshi Mori in the first book of the same name which chronologically presents the ending of a five-novel saga. According to the original author, it is not easy to adapt, yet one gets the impression that both Oshii and his screenwriter Chihiro Itō (who debuted with a wonderful, yet cheesily titled melodrama Crying Out Love in the Center of the World) have no difficulties.

Deliberately (some might say, lethargically) paced, this philosophical “fantasy” mirrors our own frustrating reality of trial and error, as it explores the themes of conflicts, memories, perception, identity and maturing (yet never aging). A masterful blend of the experienced direction, distinctive, somewhat “austere” character design, photorealistic CGI animation and Kawai’s quietly hypnotic score results in a striking piece of art which is both an eye-candy and a soul-food.

Deprived of joy, the characters are treated as if they were made of flesh and blood, not of lines and colors, as their existential anxiety and dilemmas evoke an atmosphere of spellbinding melancholy and hushed mystery. Don’t let yourself be fooled by the dogfight at the beginning – even though it is not the only action sequence, The Sky Crawlers takes more of a contemplative approach and demands an audience’s patience.

Almost a masterpiece, Oshii’s “farewell” feature anime is not only one of his best, but one of the most striking animated films of the new millennium’s first decade.

3. Open Your Mind (2005)

Created for the “Mountain of Dreams” pavilion at the World Exposition 2005 and presented on a two level multidisplay theatre, Open Your Mind (Mezame no Hakobune, lit. Ark of Awakening) is an enigmatic three-act musical drama which amalgamates sci-fi elements with plenty of mythological and religious references.

Being part of the original event must have been quite an experience, given that a digital version is impressive on its own. Initially, we can see mandala-shaped cogwheels representing the innards of a cosmic clock (or something like that) and then, six fast-moving globes of light which enter a liquid planet. In the “live-action” part of the prologue, three divine, animal-headed figures stand still in the forest shrouded in fog – presumably, they are the generals sent by the goddess Pan.

The subsequent chapters are titled after their names – (fish-faced) Sho-Ho, (bird-faced) Hyakkin and (dog-faced) Ku-Nu – and set in the realms of water, air and earth, respectively. So whether we are floating amongst the creatures of the sea, flying above a seraphim-like dove or walking beside a canine-centaur hybrid, we are overtaken by the anti-gravitational feeling of pristine tranquility.

Adding to the soothing atmosphere are the relaxing tones of blue, and Kenji Kawai’s ethereal score dominated by intoxicating polyphonic chants sung by the female septet. (If you love the soundtrack for Ghost in the Shell, there’s a great possibility you will adore the one for Open Your Mind.) Pervaded by the sound of Tubular Bells, the epilogue reveals Pan depicted similarly to the Buddhist goddess Benzaiten.

The themes of ecology, advance technology, controversial genetic modifications (code: babies and puppies) and the origin of life are intertwined into a powerful, non-narrative, out-of-the-box fantasy which seems like it is dreamt by an absolute entity.

2. Avalon (2001)

“Reality is nothing but an obsession that takes hold of us!”

And there are at least three layers of (fabricated) reality in a sci-fi drama Avalon – Mamoru Oshii and Kazunori Itō’s most accomplished feature. Its title (borrowed from the Arthurian legend) refers to the name of the illegal virtual-reality war game in which disillusioned young people seek a refuge from the dreariness of their lives in the unspecified future of Poland.

Extremely addictive, this RPG holds many dangers since it can leave its participants brain-dead. In spite of that fact, one of the best players, the bold and reserved Ash (Malgorzata Foremniak), joins a group of explorers who has been trying to find the gate to the next level. In order to achieve her goal, she will have to destroy the ghost of a little, sad-eyed girl believed to be the program’s bug.

Gorgeous in its blend of live action and “superlivemation”, Avalon is a complex and sophisticated meditation on alienation, emotional disconnect and the nature of technology, as well as the clash of (inner) self and the world, whether it is real or just an illusion. In the era of rapid computerization, its relevance is unquestionable and one might even call it prophetic.

Even though it’s two years younger than Cronenberg’s eXistenZ and the first movie in The Matrix trilogy (which rides on the back of Ghost in the Shell), both with similar themes, Avalon is a refreshing take on a cyberpunk subgenre, especially given its gloomy, eclectic aesthetics (for a very good reason, abandoned in the last twenty minutes or so).

It is like sepia tones of Stalker meet “live-action manga” meet a WWII-inspired setting upgraded with VR gadgets and modern aircrafts – all filtered through pseudo-mythology.

Plethora of Oshii’s visual trademarks or, rather, fetishes, can be recognized, from the unavoidable (pet) Basset, through the flocks of birds and all the way to heavy weapons with on-screen crosshairs. Next to the common traits of his imagery is a game master depicted as a cross between a Catholic priest and a Big Brother-esque figure – this detail in itself is enough to occupy your brain.

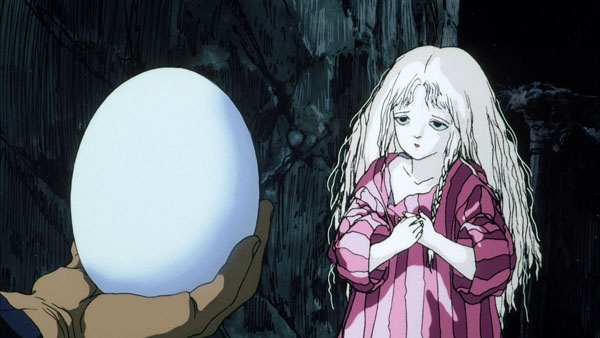

1. Angel’s Egg (1985)

“Maybe you and I and the fish exist only in the memory of a person who is gone. Maybe no one really exists and it is only raining outside. Maybe the bird never existed at all.”

If Tarkovsky, Kubrick, Bergman and Lynch had had a chance to cooperate on an anime in some parallel, numinal dimension, the end result of their brainstorming session would have probably been very alike a phantasmagoria that is Angel’s Egg (Tenshi no Tamago). In actuality, this is Mamoru Oshii’s most personal and most inscrutable work to date, as well as his magnum opus and one of the rarest examples of “un vrais auteur” anime.

At one point – and it is no secret – Oshii considered entering a seminary, but for some reason he rejected Christianity, as already stated in File 538 section, so this film – “informed by the existential desperation caused by the collapse of one’s belief system” – could be read “as an allegory of the precariousness of religious faith” (Richard Suchenski, Sense of Cinema). However, it transcends its or, rather, the director’s cryptic system of symbols and remains open to various interpretations.

Its dark, sublime, otherworldly beauty owes as much to the lyrical, metaphor-rich story as to the anime-equivalent of hypnotic long takes, Yoshitaka Amano’s superb character design, sophisticated animation supervised by Yasuhiro Nakura, and the brilliant art direction.

No words can express the intangible and indescribable in Oshii’s perplexing reflections better than a deep melancholy in the eyes of the protagonist/antagonist duo – a little girl (or an angel?) who guards a titular egg and a young man who carries a futuristic, cross-shaped weapon (a sword, perhaps?).

Also picturesque in its glorious grimness is the setting – a post-apocalyptic-like wasteland of black forests, colossal stone monuments, the remains of neo-gothic cities and a checkered desert which serves as the runway for a nightmarish, orb-shaped vessel decorated with umpteen antique statues.

The complementary soundscapes bring a rhythmic alteration of silence, murmurs of wind and water, the ringing of (invisible) church bells, the ticking of a (nonexistent) clock and Yoshihiro Kanno’s haunting ambient music and choir chants.

Once you pass through the portal to this abstract world, you are left wandering through the labyrinth of mind, dreams and soul, hoping to find the answer to a question asked at the entrance: “Who are you?”

Author Bio: Nikola Gocić is a graduate engineer of architecture, film blogger and underground comic artist from the city which the Romans called Naissus. He has a sweet tooth for Kon’s Paprika, while his favorite films include many Snow White adaptations, the most of Lynch’s oeuvre, and Oshii’s magnum opus Angel’s Egg.