Organized crime in Japan has always bordered on the affected and the legitimate. Historically, the origin of such syndicates emerged from the Edo Period when gamblers and shady merchants began forming factions. Such petty activities would become more structured until finally progressing to the administrative.

The height of the yakuza’s violence followed the Second World War as group after group fought for power and territory through bribery, corruption, and betrayal.

As of the past thirty years or so, the yakuza have become more insidious as a result of anti-gang laws in Japan. In cinema however, the mythology of the yakuza enjoys an enduring fascination. Hence, to follow, are twenty-five of the greatest of these films ranging from stylistic antiheroic tales to the gritty realism of the amoral and corrupt.

25. Afraid to Die (1960)

Directed by Yasuzo Masumura (Blind Beast, Manji, Red Angel), Karakaze-yaro features Yukio Mishima in the lead role as a reluctant yakuza who is often contradictory (but not so great as to be an enigma) and whose schemes never really work out.

He does manage to stay alive for much of the film particularly because he spends most of his time hiding out. His name is Takeo and he has just been released from prison for assaulting a rival yakuza boss. He just wants to quit the yakuza life but the rival gang wants revenge.

While a bit of a prescribed effort by Masumura, it is a unique entry in the genre for the ‘unenthusiastic yakuza’ angle and Takeo’s general ineffectiveness despite his excessive posturing. Fine performances all around with Mishima bringing his characteristic stoicism (and distinctive fatalism) and somehow managing to deliver the line, “I’m not all bad,” to the woman he’s just raped.

Also worth noting, cinematography by the great Hiroshi Murai (Sword of Doom, Samurai Assassin, Illusion of Blood) and screenplay by Ryuzo Kikushima (Yojimbo, Throne of Blood, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, The Bad Sleep Well).

24. Violent Cop (1989)

Takeshi “Beat” Kitano’s directorial debut, despite focusing on its protagonist, a disillusioned cop named Azuma, repeatedly draws parallels between police and yakuza. A bit clunky in places (as most sophomore films are), Violent Cop still manages to showcase some of Kitano’s defiant stylistics and dark humour never abandoning its proclivity for violence.

Practically everything goes wrong in Azuma’s life. He discovers his partner is selling drugs to a cruel yakuza assassin who has kidnapped his mentally-handicapped sister and the big brass are undependable.

Azuma is a textbook antihero who gradually descends into vigilantism. A very solid first effort from a talented actor and director. As an interesting side note, legendary yakuza filmmaker, Kinji Fukasaku, was originally helmed as director.

23. Inn of Evil (1971)

The only film on this list to depict yakuza in the Tokugawa era, Masaki Kobayashi paints a dreary tale of smugglers anticipating inevitable doom. The Easy Tavern is a den of thieves and murderers where even the police hesitate to venture. That is until a new sheriff begins poking around and subsequently turns up missing heralding fresh suspicion upon the denizens of the tavern.

The film portrays these criminals not as conscienceless degenerates but as misunderstood misfits rejected by society or, as one character explains, “They’re more like wild beasts than evil criminals.” When the opportunity arises for them to help a young fugitive free his fiancé from a brothel, they collectively partake in a suicide mission to help him raise the money.

Kobayashi was always fond of humanistic tales particularly ones featuring the hardships of the lower classes. Here, a drunk (Shintaro Katsu, star of many Zatoichi films, Tenchu, and the Hanzo the Razor trilogy) without a name and completely disengaged from the plot delivers a scene-stealing monologue that is the cathartic heart of the film and pretty much sums Kobayashi’s cosmology.

22. Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards! (1963)

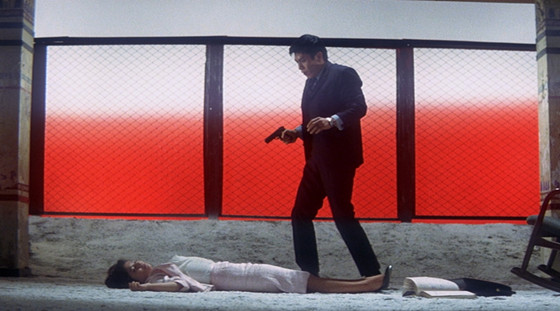

Opening with a credit sequence superimposed over a perpetually burning vehicle, Seijun Suzuki somehow manages to successfully combine sleuthing with double-crosses, dance numbers and epic gun battles, not to mention a swingin’ jazz pop score. Knee-deep in Nikkatsu studio’s “mukokuseki” era, the film proudly bears Suzuki’s flamboyant filmmaking approach.

Manabe, a small fry in the syndicate, is set to be released and a battalion of gangsters armed with machine guns and katanas wait outside a police station because they suspect him of being a snitch. To which the police commissioner explains that they have hunting licenses so there’s nothing that can be done except to simply release Manabe to a hail of gunfire. Logic.

Enter Joe Shishido playing Tajima, the suave (and only) detective of the titular Detective Bureau 2-3 dedicated to bringing down the yakuza illegal arms trade because…well, perhaps he feels like it, the why is never really specified. The audience soon comes to realise that character motivations are not the point.

Tajima infiltrates a yakuza family by staging the rescue of one of their own: Manabe. It follows that he must then hit the dance floor in order to distract the gangsters from discovering his true identity.

With two bumbling, but loyal assistants, and a police commissioner who seems to have a psychic connection (albeit begrudgingly), Tajima charms the ladies, befriends the criminals and then, more or less, betrays them all while smugly cleaning his pistol. Only you, Shishido, only you.

21. Black River (1957)

Masaki Kobayashi (Seppuku, Kwaidan, the Human Condition Trilogy) often used social and national conflict as thematic backdrops for his films. Kuroi kawa is a commentary on the increasingly widespread exploitation in postwar Japan as it bears the weight of the U.S. occupation.

The setting is the local area around the Atsugi Naval Air Base where American G.I.s pickup Japanese girls and small-time yakuza bandy about bars and brothels. Amidst boisterous military activity the black market runs rampant and prostitution and gambling are informally accepted.

Nishida is a well-mannered university student who has recently moved into a decrepit dormitory run by a tyrannical landlady lovingly dubbed “the devil.” Nishida meets Shizuko and the two develop a quaint romance which is constantly thwarted by Killer Jo, a young yakuza dressed in white who, along with Nishida’s landlady, concocts a scheme to dislodge the tenants in order to make way for a bathhouse.

Touching on themes of poverty, oppression, and social ills whilst avoiding racial propaganda in the postwar era is an impressive balancing act. Kobayashi, while incorporating noirish underpinnings, builds a slowly burning plot to an impressive and tragic climax. Academic note, the always excellent Tatsuya Nakadai appears here as Killer Jo in one of his first major film roles.

20. Tokyo Drifter (1966)

Seijun Suzuki’s ultra-stylish frolic is a fine introduction to the genre with its kaleidoscopic colours, lavish sets, unforgettable theme song, and epic gunfights.

“Phoenix” Tetsu is former yakuza who’s trying to remain legitimate in deference to his boss, Kurata, who has disbanded their gang. However, a rival gang hatches a real-estate con which inevitably forces Tetsu into self-induced exile to preserve Kurata’s reputation.

Tokyo Drifter eschewed such chivalrous tropes depicted at the time with disillusionment and social criticism. The film plays on a number of clichés, some of which were already firmly established at the time of its release (there’s an absurd barroom brawl amongst American and Japanese patrons over some dancing girls), but it’s all done with musical aplomb and, at times, sheer surrealism.

The colour palette in particular is simply vibrant and “Phoenix” Tetsu is always cool and collected. Certainly not Suzuki’s best film but easily his most memorable brimming with an avant-garde flair.

19. Gozu (2003)

Takashi Miike’s surrealist bow to Athenian melodrama was originally envisioned as a low-caliber release before garnering special attention at Cannes. Miike has always excelled at absurdist violence and Gozu is perhaps his best in such vein. Miike, who is rarely one to showcase a subtle aesthetic, instills in Gozu a broad scope of shock and metaphor.

With an unnerving yet humorous opening where Ozaki, a once seasoned yakuza, seems to lose his mind and smash a puppy to pieces, the episodic adventures involving this (often absent) madman become progressively inexplicable.

Ozaki’s boss (an older gentleman with a penchant for ladles), disturbed by the mobster’s behavior of late, orders young gangster, Minami, to drive Ozaki out into the countryside of Nagoya and kill him.

Through circumstances bordering on the mystical (an innkeeper who endlessly lactates, a guide with a questionable skin disorder, a café seeming to only employ crossdressers), Ozaki seems to die, then turns up missing, then there’s a man with a cow’s head. Go figure. One of Miike’s finest films if one doesn’t overdose on Minami’s allegorical sexual awakening along the way.

18. Yakuza Graveyard (1976)

Kinji Fukasaku was always the ultimate realist when it came to the yakuza genre. Frantic handheld cinematography, chaotic violence, and amoral characterisations were his trademark and no one did it with more conviction.

It is societal obligations and poverty which often guide an individual toward the antisocial and such individuals in Fukasaku’s films are neither praised nor condemned but merely allowed to exist (for an inevitably short time).

Taking place in Osaka, violence is likened to business and blood to commerce. Tetsuya Watari is Detective Kuro, alcoholic, unpredictable, antiestablishment, and dangerous as hell. He bears no prejudice in his treatment of yakuza whether that involves beating them to a pulp or sharing prostitutes.

It is this type of unprincipled character which Fukasaku was utterly fascinated with (whether cop or yakuza) for humanity is irresistibly dualistic regardless of one’s place in society.

Detective Kuro is contemptible of both the law and the lawless for he finds them all to be hypocrites (and in this film he is often proven right). He forms several liaisons, one in particular with a yakuza boss’ wife, Keiko (played by Lady Snowblood herself, Meiko Kaji). Together they form a bond through their shared status as outcasts.

In one apocryphal scene they make love by the beach as waves crash against the tide. Yakuza Graveyard was to become one of Fukasaku’s final yakuza films and perhaps his most unforgivingly cynical.