7. Kim Novak in Vertigo (1958)

A few years after Rear Window, the director and actor reteamed for what many now consider their masterpiece, Vertigo (not that many thought it then). Hitchcock had inadvertently helped Kelly to become princess of Monaco and, thus, had to move on to other leading ladies.

Due to a combination of circumstances, he found a somewhat unlikely leading lady in the person of Columbia studios’ post-Hayworth resident goddess, Kim Novak.

The blonde Novak had the icy allure which Hitchcock valued but, like Hayworth, she wasn’t going to be listed among the great actresses of her day. This is especially vexing in the case of Vertigo, since the assignment was demanding as the lead actress was ostensibly playing two roles. The jury is still out on Novack’s performance as the second woman in the latter half of the film but many think that the first character, a regal and cool blonde who seems to be overcome by spirits of the past, was her perfect role.

While character II is rather plainly introduced, I is given perhaps the finest entrance in a Hitchcock film ever. The detective character Stewart plays is assigned to follow the women by her supposedly worried husband, who thinks danger awaits her. The detective must see her in order to know who he is following.

The husband tells the detective that he and the wife will be dining at a fancy San Francisco restaurant the next evening. The detective is waiting at the bar for the pair to walk past. He watches as the husband and a blonde woman in a classic black evening dress finish their meal.

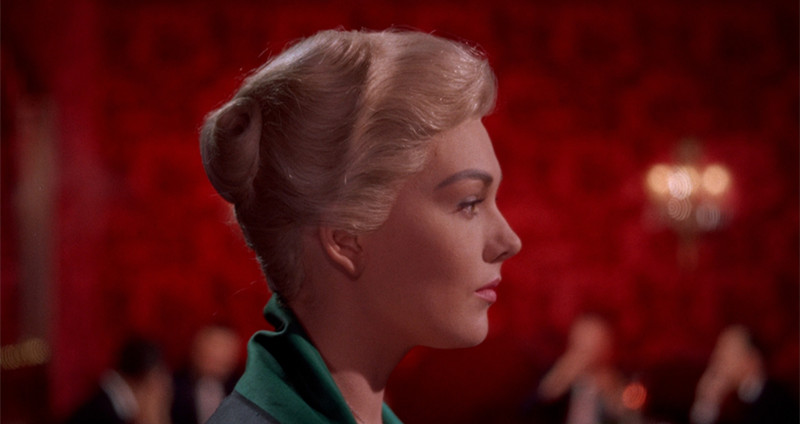

The woman has her back to the detective (and viewer) as the husband comes around and helps her out of her chair. He slips a black and deep green wrap over her shoulder which matches her chic black cocktail dress. Her pale blonde hair is in a classically chic chignon. As the detective watches her through the archway between the dining area and bar she turns and reveals the face of Kim Novak at her most ethereally beautiful with very subdued make-up.

As she and the man make their way to the door, she is left to wait for a moment while her escort (presumably) pays the bill. During this moment the detective and viewer get to observe her in profile as Hitchcock and cinematographer Robert Burks frames her in a classic cameo pose. The lighting director causes the deeply ornate red wallpaper behind her to pulsate, which causes the woman to be more pronounced. The detective and the viewer are hooked.

6. Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity (1944)

It took a lot of courage to make a film as dark and bleak as the murder/caper film Double Indemnity in the war ravaged early 40s. The crowd generally wanted escapist fare and this wasn’t that. Also, playing villains was thought to be quite risky at the time and Fred MacMurray, up until then principally a leading man in light comedies and musicals, was given pause.

Even the though and nervy Barbara Stanwyck hesitated a bit before accepting so evil a role. The extraordinary writer-director Billy Wilder rewards the pair by guiding them to performances among their most memorable as a brashly clever, but not as smart as he thinks, insurance man is drawn into a web of murder for big insurance money by a heartless spidery woman. The story is told by the man in flashback (while gunshot, as it happens).

The opening frames show a car erratically racing through the Los Angeles cityscape late at night and follow the driver (MacMurray) as he enters his office building, a coat draped over his wounded frame and goes with him into his office as he starts telling his story into a Dictaphone. He recounts how he first came to visit the woman’s home to try and renew her older husband’s car insurance policy.

The maid lets him in and the woman, who had been sunbathing on the roof comes out to the top of the stairs in a towel and an anklet which will fatally catch the man’s fascination. The film is thus off to the races at high speed.

5. Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight (2008)

Batman has undergone a lot of permutations in his history from comic book hero to camp TV fixture to semi-camp movie hero only to be resurrected in a new and far more serious (and darkly adult) movie franchise in recent years. His most colorful nemesis, in more than one way, was the multi-hued “The Joker”, a clown gone wildly wrong.

TV’s Ceaser Romero played literally as a criminal clown. Jack Nicholson’s first movie Joker portrayed him as a rather unstable criminal unhinged by a chemical accident while fighting with Batman, which leaves him chemically disfigured.

Heath Ledger dug way deeper in this film to show that the character is hopelessly troubled and that his outer clown face (which also looks quite demented in this version) throws his anti-social behavior into even greater relief. The opening scene shows him leading a gang of five robbing a Gotham City bank.

The robbery comes off but there’s never enough to share for someone like The Joker, so he kills off all the others! By the way, the gang members were also wearing clown masks in deference to their leader. The Joker is shown from the get-go as one bad guy, something poor Heath Ledger ended up finding out the hard way.

4. Christoph Waltz in Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Among his many virtues, director-writer Quentin Tarrantino may be the finest showman among the current crop of indie film makers. He knows how to set a scene and how to introduce his characters.

His cannon is full of such moments but the best of them all may well be the introduction of the chief villain of his mammoth World War II epic. SS officer Hans Landa has quite a reputation for finding and carting off Jews trying to escape fates in concentration camps. Landa is far from a fool and has the ruthless will to do his job, which is how he sees it, sans moral implications.

The opening scene of the film is, in fact, his high point in the film. He suspects that a farmer may be hiding a family of Jews. He skillfully negotiates a price with the farmer (namely, being left in peace by the SS troops for the duration of the war).

He then, upon finding out the family members are pitifully hiding under the floorboards of the farmhouse, has his men shoot through the floor, killing all but one escaping daughter. For many this opening scene made the remainder of the film anti-climatic and it put Austrian actor Christoph Waltz on the map (and made him an Oscar winner as well).

3. Omar Sharif in Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Omar Sharif is notable as the first (and only, so far) Egyptian actor to hit international stardom. In point of fact, he was only in the big leagues for most of the 60s and his fame was based on three films, Lawrence, Dr Zhivago, and Funny Girl, though his reviews for the later two weren’t the best.

However, Lawrence is now regarded as one of the great films ever and his Oscar nominated performance was surely his finest hour as an actor. In this fact-based drama concerning T.E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole), enigmatic hero of Britain’s Middle Eastern desert campaign during World War I, Sharif plays a fictitious composite character named Sheriff Ali.

Ali becomes Lawrence’s right hand man until bitter circumstances divide them in the end. The character isn’t given a grand send-off but he has one of the best entrances in film history. About a half-hour into the film, Lawrence and his native guide have stopped at a desert well during the journey taking the British officer to meet sympathetic King Fisal (Alec Guiness).

As the two men sit by the well a black spot appears on the horizon in the flat, uncluttered landscape, which allows a spectator to see for miles. The spot comes closer and closer in somewhat real time.

As the spot becomes discernable as a mounted rider dressed in black on a black camel, the native guide goes into a panic and rightly so. The figure takes out a gun and shoots him dead, since his people have no right to the well (though Lawrence is welcome). Though it’s not a great feat of acting, this scene brings Shariff into the film was a real bang.

2. Charles Bronson in Once Upon a Time in the West (1969)

When the names of great cinematic thespians are listed, action-western star Charles Bronson is pretty much never among them. Subtle, nuanced, versatile and expressive he was not.

However, his stone-like visage and deep seated sense of iron-clad toughness could be quite perfect in the correct role. Nowhere was that more in evidence than in what (aside from 1962’s The Great Escape) was surely the best of his films, spaghetti western maestro Sergio Leone’s masterpiece Once Upon A Time in the West.

This epic summing up the traditional western genre writes everything Very Large and (anti)hero’s entrance is certainly no exception. As the film opens, three desperados arrive and are waiting inside a seedy out of the way train station in the midst of a very Spanish looking western landscape. (Two of the three are played by veteran western heavies Jack Elam and Woody Strode.)

The main character, known only as “Harmonica” (for a reason revealed during the film’s run) arrives to find that he has walked into a trap upon arriving at the station. One of the bad guys expresses sympathy for having one horse too few for Harmonica to ride. Harmonica pragmatically informs the trio that, in fact, they have brought two too many. That comments alerts them but…too late.

In no time flat the three are lying dead and Harmonica now has his choice of three horses to ride. In this one sequence it becomes plain that Harmonica is more than a match for the film’s ultra-villain (Henry Fonda) and the battle will be a clash of titans.

1. Orson Welles in The Third Man (1949)

Hayworth’s one time husband, the noted Orson Welles, is remembered today as a film maker and actor in film but, long before that, he was a veteran man of the theater. He always knew the value of a great, and often deferred, entrance (look at his famed Citizen Kane, where he essentially gives himself three of them).

He told his protégée, director Peter Bogdanovich, that a perfect role was one where the other characters talked of the absent character for about an hour or so and, when the character finally appeared, the comments have done the acting for the character already. In this vein, he went on to proclaim Harry Lime, his character in director Carol Reed’s famed thriller The Third Man, as the greatest role of all time.

The story is set in motion when an old friend (Joseph Cotton) comes to bombed out post World War II Vienna at Lime’s invitation to take a job. He finds Lime supposedly dead, victim of a hit and run auto accident. The friend pursues a complex maze of leads in trying to find out what happened to Lime when, over halfway through the film, he gets a big surprise. While going down a very dark Viennese street, the man realizes that someone is following him.

Suddenly, a light is turned on in a nearby house, where the residents have been awakened by the disturbance outside. There, in the beam of light, stands the supposedly dead man (a racketeer with good reasons for faking his death, as it happens). He has a most bemused and unworried look on his face (he is supposed to be in hiding, but doesn’t seem to care that his cover is blown).

As the friend moves towards him the light goes out and when the area is lit again, the man is gone. Welles may have been right, as often he was. Harry Lime is only on screen for ten minutes, has only one substantial dramatic scene, and ended up being Welles’ only great public success.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film,cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.”