From its origins, cinema started to discover the interest of portraying group behavior on screen, either for choreographic reasons or for the narrative perks of exploring mass behavior; similarly, the theme of madness has been one of the most solid backbones of cinematic narrative in the short lifespan of cinema, an art form that was born at the start of avant-garde visual movements such as surrealism and expressionism, which all valued the role of madness as a form of description of the world and exploration of philosophical and social themes.

From Griffith and Eisenstein, the collective has always had some fascination. But it is the notion of madness and how it spreads among individuals as a viral form or as a result of some general uneasiness that guarantees the most vibrating storytelling and imagery.

10. The Falling (Carol Morley, 2014)

“The system is killing you” shouts Maisie Williams in one of the key moments of Morley’s coming of age film. The Falling mixes Picnic at Hanging Rock, punk cinema, folk horror and some of the spirit of French Nouvelle Vague directors like Louis Malle.

What is it that leads the girls of a college to simultaneous epileptic attacks, fainting, hysterical and almost rapture-like collective reactions that send everyone into panic? This is a story of sexual awakening, surely a story about repression and liberation.

The maturation of the female sexuality of the characters manifests itself into a profane, sacred, orgiastic, reinvigorating sense of being reborn, almost like a madness of uncontrolled impulses, life brutally flowing and fighting against any significant barrier. The protagonist becomes a Christ-like figure, the leader of the liberation.

The theme of a female enslaved by her instinctual, volcanic nature, the theme of the countercultural 60’s with the desperate fight against constrictions, it all manifests itself in the sinuous movements of the girls, who resemble a ballet or a Renaissance canvas, where the human figure is celebrated and revered.

All the girls feel hysterical to outside observers, but among them, they all feel sane, animated by a holy fire that brings them altogether in their journey. The way in which Morley underplays and then suddenly overplays the operatic and crazier elements of the film happens through the camera slithering in the grass, ascending through the trees, as nature becomes a metaphor for the physical ecstasy and the awakening of the senses.

What transpires is a very positive conception of madness, a madness that is necessary in growth, and the effect of the voracity of human desire to live that which is boundless and unstoppable, an instinct that can assume social and spiritual, even revolutionary connotations when projected in a society that is focused on order, fixity of rules and general repression of genuine difference and dissent.

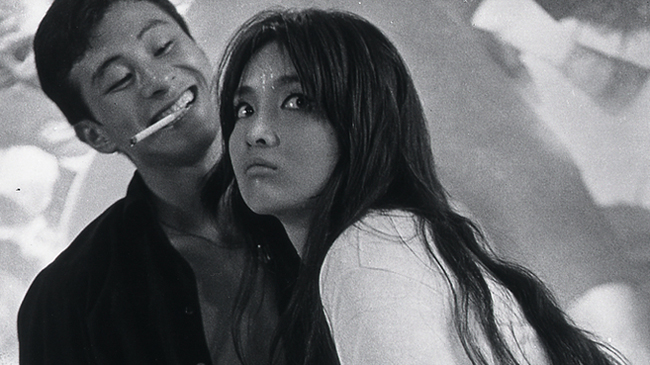

9. The Warped Ones (Koreyoshi Kurahara, 1960)

The American distribution tried to sell the film as a sexploitation film, but there is so much more to this little seen Japanese work that shares the energy of the first Godard films. It is a film about youth, killers and jazz, and it is frantic in its editing and in the movements of the characters, who are fast speaking and uncontainable.

The soundtrack makes use of free jazz, a style that was breaking boundaries at the time, just like the film was breaking the formalities of the Japanese studio system, and the youth of the time was attempting the first steps at establishing a counterculture to a system that, after the war and the recovery, was considered old and was in peril because of a newfound economic stability that was tipping towards richness and progress. The frantic, crazy energy is an element of rebellion, but also excitement.

An exasperating, eager wait for better times and an anxiety for a future that looks bright. The film’s quieter moments contrast with the faster moments, exploring the tonal shifts that are now one of the main features of the most beloved genres of Japanese cinema, of people like Miike or Sono. One of the first examples of the revolutionary, unruly power of the surging New Wave.

8. A Field in England (Ben Wheatley, 2012)

Bergman and Wheatley, and the silence of God. It is incredible how much the notion of hysteria and madness coincides with the absence of God, of a supreme ruler that guarantees the order of all things.

In Wheatley, the craziness does not pertain to the people alone, but to the grass, the sky and the sun (in one of the sequences, we see a black sun, a devouring void).

It is not clear what is haunting the land, but we begin during a battle, an example of the violence of men against men, the paradox of conflict, the uncommunicable, unexplainable reality of war, blood, death and chaos of the battle.

We have to ask ourselves whether the characters are mad or the world around them is so mad that they are actually normal, whether there is a Geist, a Demon, a spirit that governs all the horror, an inverted God, thirsty for destruction. In Wheatley’s film, madness will not constitute a response, an opponent to Order, a twin, but only a dark pool in which to sink.

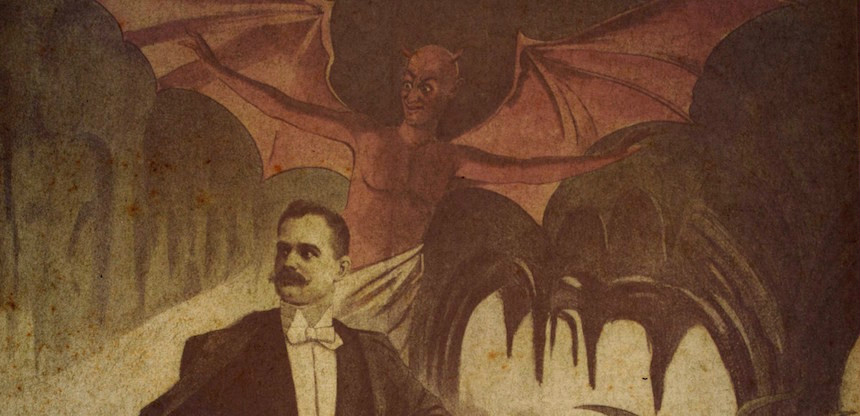

7. Fury of the Demon (Fabien Delage, 2016)

Cinema is, indeed, a form of obsession. This is especially true for certain collectors of the early age of cinema, who are absolutely devoted to rediscovering rare objects, rare films, and lost gems of the pioneering ages. From this premise, Fabien Delage built a clever mockumentary, focused on a lost film by Georges Melies that supposedly can drive people mad.

The film is enriched by cameos of directors and journalists, along with archive footage. According to the film, Melies’ lost work was shown three times, and every time it caused outbursts of mass hysteria.

It is suggested that the film could be the work of Sicarious, a disciple of Meliès that was interested in the occult and hung around shady, esoteric bars at the end of the Nineteenth century. Fury is very erudite and at one point cites Lovecraft, in connection to the fact that cinema is a medium that transports us to the unknowable mysteries of the universe and can generate the sort of cosmic horror that his writing would generate.

Delage, basically, is able to effectively link the medium of film to a form of madness, or subversive hysteria, emphasizing the power that this art form has had since its inception (we can think about the legendary escape from the cinema that took place at first screening of the Lumiere brothers’ film about a train).

Interestingly enough, Meliès was in fact a magician, reinforcing this perception of cinema as an anathema, something that viscerally takes hold of the viewer, an astral possession, to invoke Lovecraft again, that can have elevating and sublimely positive effects, but also completely rip him apart.

6. Hukkle (Gyorgy Palfi, 2002)

In the films of Gyorgy Palfi, there is a lot of David Lynch, a lot of Herzog, a lot of Cronenberg, and, in general, a lot of weird and disturbing elements.

This film is based on the Angel Makers of Nagyrèv, a community of women who poisoned an enormous number of people under the control of a midwife.

The women killed their husbands systematically, then proceeded to eliminate many of their parents, for various reasons. Their madness took the form of an organized cult of murder, a shared delusion that never fails to capture the imagination of artists, but weirdly, only Palfi decided to make a film about these women, and he did it by choosing a very experimental and rarified approach to the events.

The events unfold in a land that breathes eternity, where nothing seems to happen, and Palfi indulges in a series of expressionistic sequences, focusing on little details, on a sense of discomfort that originates from an intangible evil, and the nature of this madness, this evil, remains impossible to discover.

Maybe it’s just a fracture of the human nature, a deficit that does not need an explanation. This serenity, this calmness to the madness, is what Palfi is interested in: to him, the most interesting aspect of a human being is the Underneath, which is full of monsters, and in that he is very Lynchian.

The madness is mostly implied through omens of various kinds – a catfish eating another fish, things slowly rolling down and out of frame, an old woman entering a cave-like habitation, an old witch from a fairy tale, and the most haunting of them, an owl looking firmly at the camera, emerging from the dark, a messenger of Death.