“You don’t know much about women, do you Stephen Meek?”

– Emily Tetherow (played by Michelle Williams)

Go West, young ma’am

“Oregon Territory, 1845” reads a rough-hewn hand-drawn title card that opens Meek’s Cutoff (2010), the fourth feature by 52-year-old, Miami-born filmmaker Kelly Reichardt (her sixth, Certain Women, hits select North American theaters later this year).

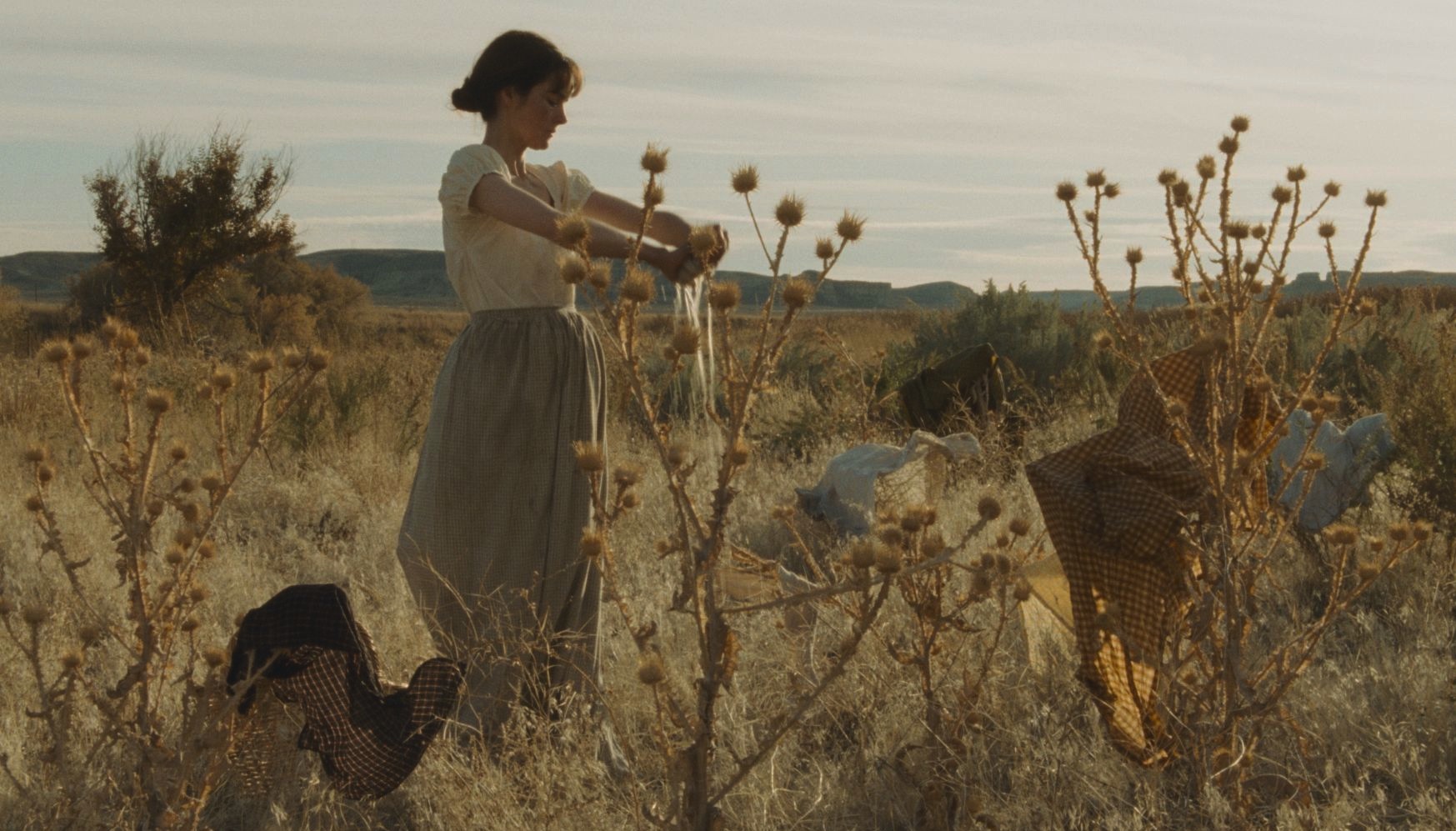

Over the wailing wind and the heavy grouse of wheels the viewer is jostled into the high desert, glimpsing begrimed and dour faces of men and women, their overtaxed beasts of burden, their slovenly covered wagons, and a sinking trepidation that they are through.

One of the men pitiably takes pause near an ashen clod of driftwood and scratches into it with his knife the word “LOST.” Thus begins an eerie, unsettling film, Meek’s Cutoff, which enacts a desperate situation where only a few moves remain left to be played by its frayed and ill-fated characters.

It’s a Western, of sorts, impossibly bleak, familiar, at times, but singular and often mystifying in its sun-bleached and dust-veiled designs. As nameable for its whorl-like detours and its omissions, Reichardt is methodical and together with what she puts on view, making for a horse opera like you’ve never seen. Hollywood glitz so often associated with the Western is here totally renounced in favor of malaise and even cruelty, but all with an artist’s teasing yet pronounced touch.

“Directed from Jon Raymond’s fact-based script, this suggestively allegorical, discreetly trippy Western recalls Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and even Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: The Wrath of God in its evocation of frontier surrealism and manifest-destiny madness; the Reichardt approach is, however, more stringent and pointed in its weirdness.”

– J. Hoberman, Village Voice

Alone and forsaken

Following three pioneering families’ trek along the uncertain and untamed Oregon Trail, their goal is to establish themselves in the Pacific Northwest and build new lives there, but the migration is unforgiving as their small caravan of ox-drawn covered wagons, horses, and steers have scarcely enough food and water to sustain them.

Their guide, Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood of The Sweet Hereafter, and The Place Beyond the Pines), like a snake in the grass, has hustled them with tall tales of wealth and bountiful soil in stomping grounds known only to him. His aloof exterior, undependable gaze, and racist ire mark him as villain straight away.

The rest of the pioneer settlers include Emily Tetherow (the luminous Michelle Williams, three time Oscar nominee for Brokeback Mountain, Blue Valentine, and My Week with Marilyn, respectively), her husband Solomon (Will Patton, Jesus’ Son), Thomas Gately (Paul Dano, There Will Be Blood), his pregnant wife, Millie (Zoe Kazan, Ruby Sparks) and Glory White (Shirley Henderson of Bridget Jones and Trainspotting fame), amongst them.

As ideas of isolation, mistrust, and being hopelessly lost intensify, Meek narrowly avoids being lynched when they capture a Native American, an unnamed Cayuse Indian (Ron Rendeaux, The Missing)—their confirmed enemy, according to Meek—who, as the fates decree, may just be their one and only lifeline, capable of leading them to either asylum or annihilation.

“To set aside its many other accomplishments, Meek’s Cutoff is the first film I’ve seen that evokes what must have been the reality of wagon trains to the West. They were grueling, dirty, thirsty, burning and freezing ordeals.”

– Roger Ebert

No place to fall

Part of Reichardt’s stylistic stratagem is to use the long game approach, a satisfying though perhaps arduous for some, slow-cinema sweep. Overrun with observational and abstractive long takes that would make Michelangelo Antonioni smile, Meek’s Cutoff also works as a Revisionist Western.

Somewhere hardwired in its dust-mottled and dog-eared frame are the same chromosomes that connect John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and yet some of the chimera of Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) permeates here, too. Dano’s cherub-like visage also evokes much of PT Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007), and not just by proxy, also in heaviness in heart, as well as in tenacity and tone.

There is great, taut tension, and a slowly sinking feeling of cataclysm that rewards those who can relinquish to Reichardt’s lure. Shot in many ways like the classic Westerns, utilizing the 1:1.33 screen ratio—the standard of Hollywood’s Golden Era—Reichardt’s frame corrals her characters in their own personal impasse as opposed to the John Ford overpowering landscape approach.

It’s a risky maneuver, which, thanks to cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt (The Bling Ring, Night Moves), works like a bizarre birthstone.

“Kelly knows what she wants. Possibly more than any filmmaker I’ve worked with. It’s a place where I feel my ideas are always welcomed, but Kelly is very specific about what she wants.”

– Michelle Williams

While Meek’s Cutoff works well as a pensive musing on homesteader survival and as an impeachment of Manifest Destiny and imperial expansion, it also contains attenuated matriarchal temperament, which is pretty commonplace for a seer such as Reichardt. She wisely rebuffs any platitudes with Rendeaux’s Cayuse captive.

He’s no victim and nor is he the noble savage, instead he’s a judicious, even shrewd, survivor. And Williams’ Emily symbolizes some of the good scout liberal humanism this sort of tale might require, but even this is supplanted in the face of uncertainty and arrangement.

Maybe the heartbreak and reparation in 2008’s Wendy and Lucy is more of a 24-carat cache (it’s my favorite film of Reichardt’s, at least thus far), but Meek’s Cutoff deserves distinction for its enterprise and understanding, it almost plays like a sneering, offbeat episode of Little House on the Prairie. The moments of listlessness and ennui are tempered with a fascinating, lucid intimacy in a genre film that is, oddly and impossibly, an unadorned lyrical feat of strength.

“Women, women are created of the principle of chaos. The chaos of creation, order, bringing new things into the world… Men are created on the principle of destruction. It’s like cleansing, ordering, destruction…”

– Stephen Meek (played by Bruce Greenwood)

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.