“Céline and Julie Go Boating is a do it yourself guide to rediscovering the delights of the street outside, and of the idiots all around you, here’s where we see Rivette first moving toward Shakespeare, and the world as all fools’ paradise.”

– David Phelps

Usually it began like this

Playfully reflecting silent-era idiosyncrasy an on-screen title proclaims:“Usually it began like this.” And with that amusing suggestion, one of stopgap solicitation and questionable sincerity, Cahiers du Cinéma dissident Jacques Rivette’s 1974 mindfuck marvel Céline and Julie Go Boating comes ashore.

My personal connection and passion for this film stems from a few suitably defiant and naive places. For starters, Céline and Julie Go Boating is an incredibly difficult film to track down anywhere in North America.

Criminally, it does not yet exist in Blu-Ray and Region 1 DVD formats are long out of print –– Criterion, how could you drop the ball on this one? –– and I’ve yet to be so fortunate as to be in a city whose revival houses or repertory cinemas have been showing it.

My other reasons for doting over this celluloid jewel hinges on the magnetism of the leads (more on them in a moment) and the obvious influence this film has had on one of my personal film heroes, David Lynch. Much of Lynch’s venerated delectus could only exist, it would seem, in a post-Céline and Julie galaxy (most notably Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive).

Sure, it helps that I love the French New Wave but I don’t feel that Rivette is the best director to develop from that movement, nor do I feel his films do much to define it. Céline and Julie is an eccentric anomaly, bohemian, byzantine, and wonderfully insane.

“Jacques Rivette’s comic feminist extravaganza is as scary and unsettling in its narrative high jinks as it is exhilarating in its uninhibited slapstick… The elaborate Hitchcockian doublings are so beautifully worked out that this movie steadily grows in resonance and power.”

– Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader

The house of the spirits

An odd espousal of Éric Rohmer’s (Claire’s Knee, Pauline at the Beach) intimate female exploration—in no way voyeuristic or male-centric—and Luis Buñuel’s (L’Age d’Or, The Exterminating Angel) surrealism, Rivette respects his subjects and his audience joyously.

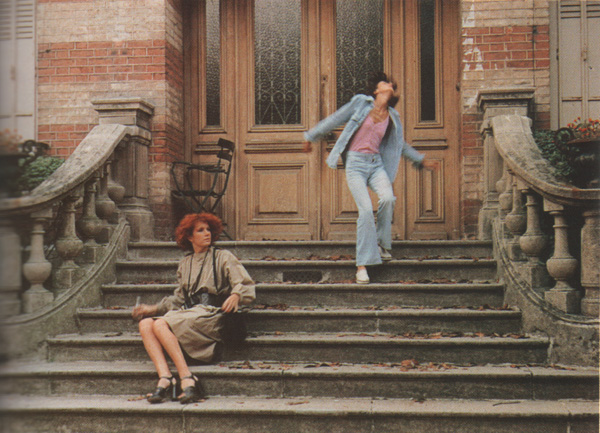

His film floods with clues, solutions, patterns, and possibilities. Céline (Juliet Berto, wonderful) is a cabaret illusionist and Julie (Dominique Labourier, outstanding), is a librarian and an occult aficionado. The two become fast friends, quite literally, when Julie first sees Céline, who, like the White Rabbit, runs past her at full-throttle, dropping her glove.

Julie pursues her hotly and a life-altering friendship blooms. Many allusions to Alice in Wonderland will follow as the duo leap into a shaggy dog skein as they become detectives on a trail that stubs their toes on a mysterious mansion where a Gothic soap, like a Möbius strip melodrama complete with unhappy oddballs (in startling operatic whiteface) appear damned in an unremitting loop.

“The miracle of [Céline and Julie Go Boating] is that all of its disparate elements are mixed into the final cut that the film achieves that rarest of qualities: it creates a world of its own, a world in which everything on screen represents an opening for the viewer.”

– Glenn Kenny

I want candy

This curious cadre (which includes Nouvelle Vague notables Jean Douchet and Barbet Schroeder), denizens of 7 bis, rue du Nadir-aux-Pommes, Paris, are perhaps ghosts, continuously reenacting a Proust-like saga, haunting the house, unawares of their spectral entanglement. Moments of creeping terror are balanced with frenzied farce.

And did I mention that these dreamlike denizens can only be visited and viewed when Céline and Julie suck on magical candies? And that amnesia also affects the pair, impeding their attempts to solve the mounting mystery? It’s a gas, that soon assumes a logic found commonly in dreams, where the observer (here Céline and Julie) soon takes part in what is being observed. And as a spectator, the viewer also feels the weight of the fourth wall which soon starts to relax as it crumbles.

“Rivette’s signature special effect is the uncanny impression that the story is being generated by the characters as we watch; or, spookier and more thrilling still, by the very act of our watching… it’s not just that Céline and Julie holds up to repeat viewings; it’s very point is its seemingly infinite repeatability, its mysterious capacity to surprise both first-time viewers and those who know it as well as a magician reciting an incantation.”

– Dennis Lim, The New York Times

Come sail your ships around me

Céline and Julie seem to be incendiary fabulists as the film progresses, even becoming subversive simulacrum for us, the audience. It’s a pleasure few films can truthfully afford as it almost morphs into a fictional DIY kit for the viewer; armchair acid for the at-home audience (or amping up the shared experience for those fortunate enough to be watching in a theatre), purple haze as soon as you press play.

It’s a victory for Rivette that he’d provide a map for such uncharted territory as this. Territory, I must express, Rivette shares with magical-realist author Jorge Luis Borge, particularly in their shared affinity for phantom-like doppelgängers (the film is also alternately titled Phantom Ladies Over Paris, most suitably).

Truth and bright water

But truthfully, such audience involvement and literary allusion acceptance does depend a lot on the viewer and how willing they are to follow Céline and Julie down the rabbit hole. Even if the hypnagogic highs aren’t attainable for the uptight viewer there’s an exemplary feminist narrative that also brings bottomless rewards.

While Rivette deserves his auteur status he shares the storytelling strengths and narrative voice with his esteemed leads. Both Berto and Labourier are outstanding, not just in their portrayals but in their assimilating and actualizing of what’s on screen.

Rivette gave them carte blanche to bring their own material to the movie, adding authorship not only to the film-within-the-film motif but to the entirety of the project. The youthful enthusiasm they communicate, their constant goofing and chumming around, somehow upgrades every aspect of the story. The imagination and the daring shared by these artists is a serious source of inspiration, how could it not be?

There were lots of improvised elements that Rivette wisely kept in the film (perhaps partially owing to the massive 192 minute running time), and despite my excited hyperbole, it isn’t all sweetness and light. I’m deliberately not discussing many elements of the film, not wanting to examine any spoilers or dissect plot points. But I will happily divulge that Céline and Julie happily betrays several explanations and delights in many ways its gracious frustrations.

And we’ll all float on okay

The titular aquatic voyage does literally occur, late in the third act, if that matters at all. But the very title, Céline and Julie Go Boating, also works well metaphorically for the notion that these two friends skirr into dark and attempt the taming of unnamed waters. The voyage Céline and Julie edge us on springs from impulses as expansive as our own imagination allows. Their desires and dreams are seductive and sweet like the crazy magic candy they partake of.

When we awaken from a dream and feel light-headed with the fading memory of a wayfaring adventure we cannot take into the waking world, that sensation, which can at times feel inexhaustible, is what this gilt-edged film gives back. It is a populated and otherworldly place that will forever welcome you back into its forgetful but forgiving embrace.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.