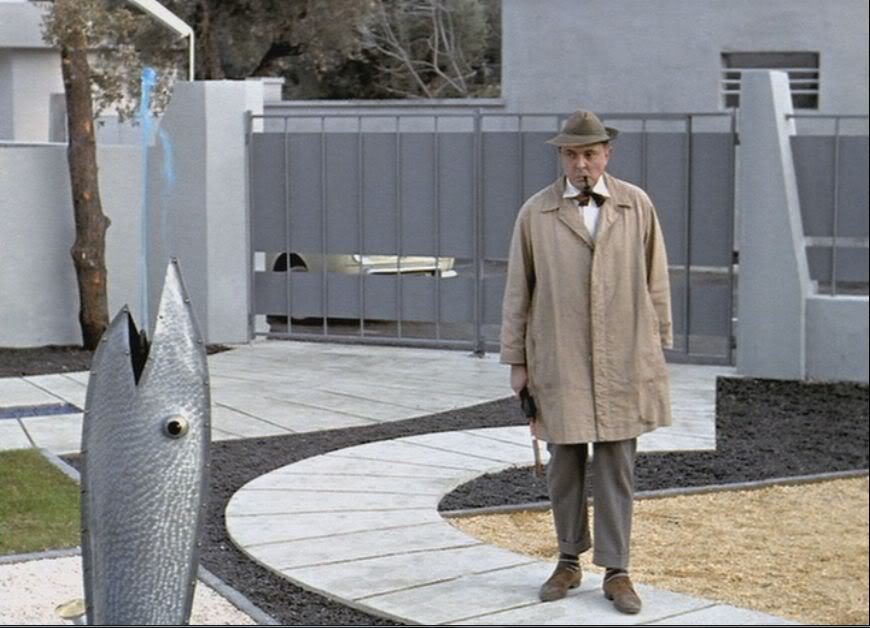

24. Mon Oncle (1958)

For many, comedy on film was at its peak in the silent era with its universal humor and easily understandable pantomime and jokes. Though Charles Chaplin held out until 1936, Hollywood largely ended the silent years in 1928 and also largely forgot about this golden period of comedy.

Happily Europeans, the French in particular, remembered and venerated this time and, more astoundingly, fostered adherents to silent comedy who actually practiced this unique art form. There was no more prominent practitioner of this sub-genre than Jacques Tati.

Though his films (only five and a TV special in total!) technically had music, sound effects, and extraneous dialogue, Tati, virtually always in the role of the gangly, warm-hearted, somewhat out of touch M. Hulot, was always silent and large patches of his films have no dialog at all.

Though his second Hulot film (and third ever, after 1948’s charming debut Jour de Fete), Mon Oncle (My Uncle), his first in color was a huge international hit (and his Academy Award winner as well).

The story was another simple affair: Hulot’s Nuevo riche brother and sister in law want to bring him in line in order to meet their now lofty standards and a big part of that is marrying him off, whether he likes it or not! Only their young son understands and supports Hulot. Some always found Tati and his films a bit twee but their charm and ingenuity can’t be questioned.

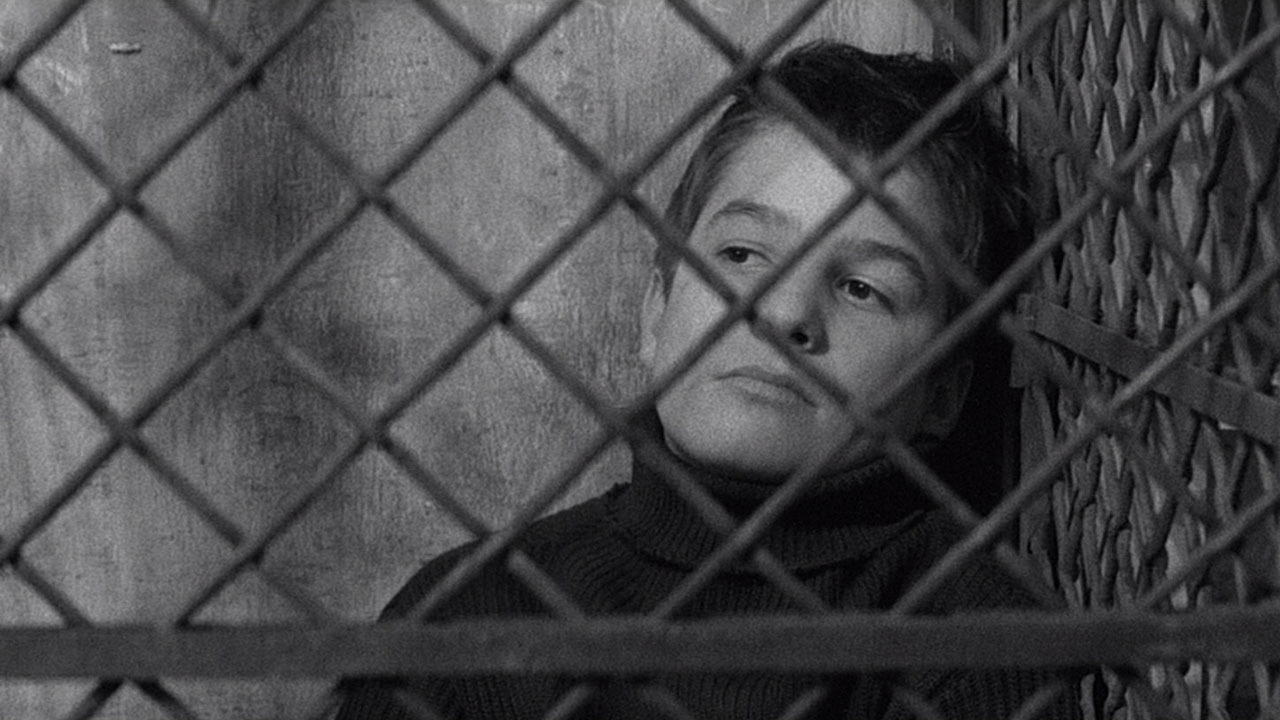

25. The 400 Blows (1959)

Very many of the key members of France’s Nouvelle Vague began their careers as writers for the prestigious and influential film magazine Cahiers du Cinema. While several great careers were fostered under the auspices of this journal, none were more prestigious than that of Francois Truffaut.

Truffaut had experienced a troubled childhood and youth, one largely redeemed by his love of film, and he was also a great lover of many certain aspects of Hollywood cinema, especially genres which weren’t highly prized at the time. However, like others members of the movement, he didn’t want to make films of that type himself but opted for the much more personal cinema the movement championed.

Nowhere was this more in evidence than Truffaut’s stunning debut, The 400 Blows. This film is, quite literally, the story of the director-writer’s turbulent adolescent years (only the names are changed).

What might well have been a grim tale is told with marvelously free technique, surprising traces of humor, which only deepen the moving quality of drama, and an excellent performance at the center in the person of young actor Jean-Pierre Leaud. Leaud would go on to a major career in films but the centerpiece of that career is this and the four follow-up detailing the succeeding years of the character’s life (a clear precedent for 2014’s Boyhood) , the director’s autobiography on film.

26. Breathless (1960)

A compatriot of Truffaut’s was the most influential Jean-Luc Goddard, though, unlike Truffaut, if he ever loved anything inordinately, he kept it resolutely to himself. Though he professed a devotion to grittier Hollywood/indie fare (his debut was perversely dedicated to the lowbrow US studio Monogram), he didn’t so much make films as anti-films.

Virtually all of his films were idiosyncratic and personalized dissections of formulaic genre pictures. His first, and another stunning debut, was Breathless (A Bout de Souffle), his anti-gangster film.

Really punkish petty thug Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo in a career making performance) commits a bunch of crimes, principally killing a policeman, and takes it on the lam, ending up in Paris and falling into the somewhat indifferent arms of his old flame, American Patricia (Jean Seberg, a Hollywood casualty redeeming her career, among the international set, at least). Sadly, far from being a moll with a heart of gold, she is not to be trusted.

The film proceeds at a breakneck pace (hence the title), breaks almost all the conventions of formal, traditional film making (most notably continuity) and signaled a new era in youth-oriented films. Today it may look a little less fresh due to the many films bearing traces of its influence but the original still bears the mark of youthful enterprise.

27. Eyes Without A Face (1960)

Horror is a rather debased genre in Hollywood but, when handled by a serious artist, it’s treated rather more seriously outside of the US. A supreme example of this is Eyes Without a Face. The film is the product of Georges Franju, who was not a truly major film maker and who had previously had his most notable moment with the short subject Le Sang des Betes (Blood of the Beasts, 1948), a film detailing the all too real horrors of the meat packing industry.

Eyes, which does not have supernatural elements, concerns a brilliant surgeon/scientist (the great French actor Pierre Brasseur) who is responsible for destroying his beloved daughter’s face (Edith Scob in an excellent pantomime performance as the girl) in an accident.

In a frantic effort to put things right, he kidnaps young women, taking them to his clinic and proceeding to remove their faces in a vain effort to graft them onto his daughter.

This could easily be the ingredients of a cheap piece of horror schlock but Fanju gives the film a full array of disturbing shocks and also a deep layer of emotion than found in a traditional horror film. (The viewer especially feels empathy for the faceless daughter, mute behind a mask.) The film was not a blockbuster upon release but time has increased its stature greatly in recent times.

28. Black Sunday (1960)

Though no critics, save hard-core genre ones, would ever put the sub-genre at the top of their list, the Italian ultra-violent horror films known as Giallo have done their fair share towards introduction mostly unsuspecting viewers to films from foreign shores. These visually stylish and quite hyper violent films are now a staple of very many horror fans list of favorites.

One of the earliest practitioners of this form, and one of the best, was Italy’s Mario Bava. Though he had salvaged a number of productions abandoned by temperamental directors, his official debut as a director was this supremely atmospheric film.

Taken from a short story by noted Russian writer Nicolai Gogal, Black Sunday (originally La Maschera Del Demonico/Mask of the Demon) tells the tale of a witch tortured and put to a supposed death in 17th century Moldavia (and no one seeing this film at a certain age will ever forget the mask of spikes driven into her face during the first scene). A quirk of fate releases her spirit some 200 years later and she seeks vengeance on the family (her own) which caused her downfall.

Though highbrow critics looked down upon the film, genre aficionados appreciated it for being a fine job of craftsmanship (with superb black and white cinematography) and the film introduced Scottish born actress Barbara Steele (who spent most of her career in continental Europe), whose performance as both the witch and her innocent descendant helped to make her a later day horror icon.

29. An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

Japan’s Yasurjiro Ozu is simply one of the great film makers-ever. It took a while for critics/historians and viewers outside of Japan to realize this as Ozu was one of the most intrinsically Japanese of directors. However, though his films were rooted deeply in Japanese culture, they are also explorations/celebrations of universal human nature, most explicitly family relationships (rather unusual in that Ozu never married nor had children).

He made films from the silent era in the 1920s until this film, his last and a rare color production, made a year before his rather premature death. As ever, this is a very touching family drama. A widower is faced with either selfishly keeping his unmarried, dutiful daughter with him or lovingly letting her go via marriage with a man with whom she has fallen in love. The outcome is never doubted but, as usual with Ozu, it’s all about the emotions and relationships in getting to the outcome. This is a late masterpiece.

30. A Hard Day’s Night (1964)

Life, let alone the cinema, can be filled with happy accidents, things that turn out way better than expected. The British-made rock musical A Hard Day’s Night is one of the biggest, and happiest. Rock has always mixed uneasily with the movies (mainly different audiences and expectations and forms). Rock/pop films had very generally poor reception (rather deserved).

US based production company UA wanted a hit album for its record division and were willing to shell out only a pretty modest amount for a film centering around a European based rock group only then beginning to become well known outside of that continent.

Due to that, they accepted as director Richard Lester, an American who had spent the major part of his career in England and who had only directed one prior film and, more importantly, the Oscar nominated short, The Running, Jumping, Standing Still Film (significantly a big comedy favorite of The Beatles).

The company also accepted British TV writer Alun Owen as the film’s writer (amazingly, he returned to TV after the success of this film). The two men smartly realized that the four young men could 1 only really play themselves (or variations thereof) and 2 could only plausibly be put in so many situations (a problem which presented itself in the commercially successful follow-up Help! in 1965 and presaged the end of the group’s film careers).

To that end, the film concerns an exaggerated (though not by that much, as it turned out) version of what roughly 24 hours during a tour would be like for the group as they deal with obtuse reporters, stuffy officials, hangers-on, a problematic grandfather (an invention) and, above all, some majorly Beatles-crazed fans.

Lester was wildly inventive in both the film’s loose comic structure and zippy visuals (though he does not care for the appellation, many think him the father of the music video). The topper is that The Beatles had real screen presence and brought off the script’s comic implications in fine style.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.