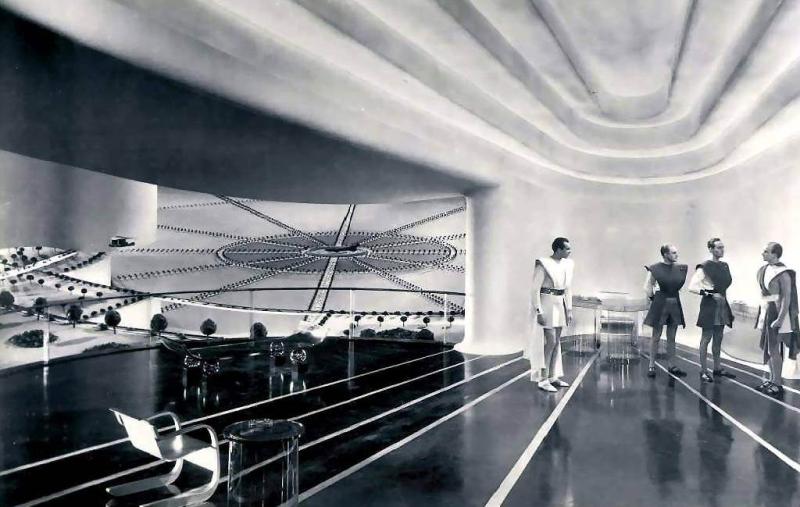

8. Things to Come (Alexander Korda, 1936)

“Things to Come” was one of the better-realized cases of utopian architecture represented on film, a project that brought together the great sci-fi writers H.G. Wells, Vincent Korda, Moholy Nagy, William Cameron Menzies, and many others to create the vision of the Everytown of 2036, a form of speculative architecture that was very popular in the futuristic and modernist era.

The film analyzed progress, especially the architectural and technological progress, and how it brings consequences, including a re-shaping of the world order and de-humanization.

The architecture in the film is a fusion of Bauhaus, Art Deco and Le Corbusier’s theories, with a tendency to the vertical development of the constructions, big and bright interiors that have white tonalities and a style that anticipates a Kubrickian sensibility, the inhuman emotional stillness of our technological creations, and the miniaturizing and estranging effect that humans experience. The main area of the Everytown is a futuristic neo-gothic building that abolishes spatial linearity.

The film is highly suspicious of the benefits of progress and the interiors have a moderate expressionistic feel to them with slightly non-harmonious camera angles, close-ups and peculiar pans, with an emphasis on impartiality and detail that is typical of expressionism, that accentuates a sense of discomfort.

It is a fear that the Everytown could end up devouring the human soul, that with technological progress comes an endless process of dehumanization.

9. Holy Motors (Leos Carax, 2012)

Deserted cities of the heart: it is not just the title of a song by Cream, it is the empty churches, the empty halls, empty car parks, the empty industrial building in which Leos Carax set “Holy Motors”.

In a film that is about the nature of cinema, the nature of reality and the nature of the dream, the halls and the architectural spaces that Carax explores take the role of canvas where the human subjectivity can create its illusions and its creations, but at the same time perceive the discomforting emptiness and loneliness of its condition that can only be filled by the power of art, the power of the self.

The enclosed spaces that the film shows, like the bedroom of the first scene that magically turns into a passage into a cinema in a surrealist twist, do not communicate the idea of being trapped, like they traditionally would, but as Lavant is constantly running through these spaces, jumping and falling, it creates the atmosphere of a surrealist playground, a theatre of dreams.

Carax uses his camera judiciously, without accelerating the pace, in order to let the interiors breathe and the scenes unfold in a free spatial and temporal structure that is not coercive and allows the film to breathe in a fluid free form.

10. Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (Wang Bing, 2003)

Wang Bing explores the end of heavy industry, and the way capitalism destroys its own structures in order to have new ones, but leaves the people behind. This documentary is a 9-hour epic that explores the decline of the industrial Tiexi district. With incredibly tactile cinematography, Wang Bing explores the rotting corpses of metal factories, housing blocks, rail yards being corrupted by rust, snow and other elements while people suffer the consequences.

Just like other Chinese contemporaries, like Zhao Liang and Jia Zhangke, Wang Bing has an interest in exploring the nakedness of the architecture, its decomposing heart of iron, the raw parts of construction that look like detached limbs of a dying body.

The film approaches architecture like a surgeon would approach a tumor inside a body, and in this case the body that it is investigating is a metaphor for the entire industrial apparatus, which is shown as an old, unstable building full of hazardous poisons and infections.

The architecture in the film is infected, is terminally ill, and appears like a weird metallic monument commemorating something that belongs in the past.

11. The Fall of House of Usher (Jean Epstein, 1928)

The architecture, the spires and the corridors were a big part of the scary factor in gothic literature. In Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Fall of the House of Usher”, the house is the one to fear.

To create the terror, French director Jean Epstein envisioned a hall of immense emptiness with few pieces of furniture that look like lost children; he used a mixture of gothic style in the stone staircases and the verticality of it all, but also used the sensibilities of his age, disturbing small details taken from expressionism, and most importantly, the presence of curtains around the room, moved by a mysterious wind that haunts the house, to give the space a surrealistic and operatic magic.

In the way Epstein holds the frame, the viewer is never allowed to see the entirety of the hall, so that once the uneasiness and the menacing nature of the place becomes evident, the spectator is constantly terrorized by the dark corners of the room and the edges of the frame.

In the final sequences, the architecture reveals itself in all its gothic power, with strange forms that look like ghost trees and a petrified forest immersed in mist and fire. It is the architectural realization of an evil spell, an evil entity that silently watches and torments the living.

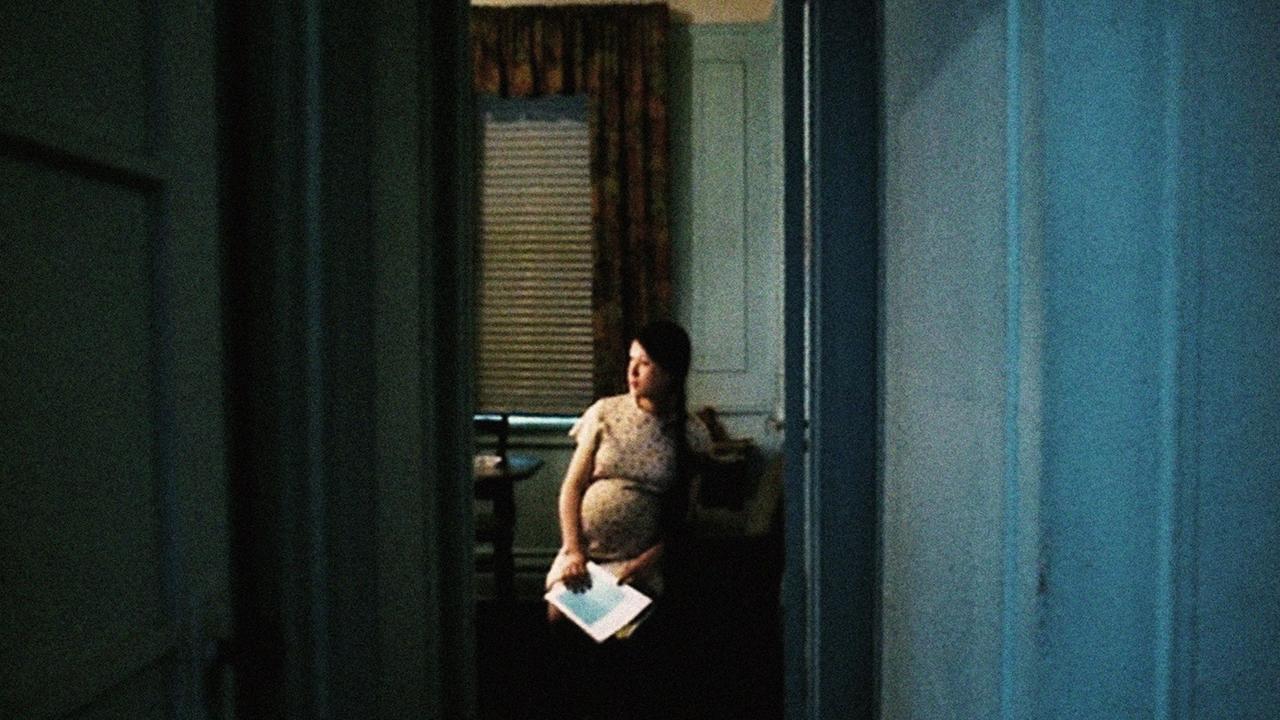

12. Colossal Youth (Pedro Costa, 2006)

Some spaces carry with them sociological values. Rio de Janeiro’s favelas immediately relates one to a specific social context, and the same can be said for the Fontainhas neighborhood in Lisbon, a slum where Pedro Costa shot three of his docufiction style films.

Being a master of the close up, Costa rarely leaves the point of view of his protagonists in favor of seeing a bigger picture. He embraces the mindset of his protagonist, who cannot see the way out of their poverty and are bound, almost by symbiosis, to the poor urban space they live in. This becomes their reality and their identity.

The architecture landscape is made up of bare, cubical buildings, with a color range that moves from white to pitch black, and it is a symbol of poverty, of social disparity and the metaphorical prison of the poorest classes of society.

Many times the buildings are shot in a way that makes the sky barely visible, augmenting the sense of entrapment. The architecture is Colossal Youth and at the same time a denouncement, a realistic account of a depressed area and a sociological analysis of the condition of the lower classes.

13. Red Desert (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1964)

“Red Desert” is one the finest examples of cinema of alienation. In this case, the petrochemical plant, the deafening noises, the smoke, the greys and the reds that dominate the film are the background to a psychological tale of depression, the nature of pain and the nature of existence. Antonioni inspired all the great Asian directors that explored Dark Materialism, the corruption of the materials, of the architecture, from Tsai Ming Liang to Wang Bing.

The colors that dominate the industrial landscape are very saturated, yellows, greens and browns, to create a dreamlike and also nauseating setting with touches of psychedelia. The protagonists live a conflict between the materialistic and deterministic existence that seems to be connected with their surroundings. Their moral decay is made evident through the misty setting and the ominous constructions that scaringly dominate the world like an iron jury.

Antonioni, being a master, also offers the viewer the opposite vision, an almost primitive vision of an unrestricted life, as fluid of pure possibility, when the characters ecstatically spend some time on an idyllic beach.

14. Hotel Monterey (Chantal Akerman, 1972)

Chantal Akerman explored the Upper West Side Hotel in New York in her avant-garde film inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper. Akerman explores the building with static shots, soft lights, slow pans and absent sound. She explores the soul of the architecture, the mysterious nature of a closed box that is cut from the outside. To her, the hotel is like an artificial bubble, a surface inside another surface, a fractal reality, a dream inside a dream.

Akerman is also interested in whether the architecture has a soul, a life of its own. The slow rhythm tries to penetrate the motionless heart of the walls, and Akerman indulges in exploring the dark corners at the end of corridors, the corners of the rooms, in the style of David Lynch, as if looking for a path inside the subconscious of the building, the submerged nature beyond its appearance.

15. Surface Tension (Hollis Frampton, 1968)

Hollis Frampton was an icon of avant-garde filmmaking with a particular sensibility for the city of New York, just like Bill Cunningham was an icon of street photography in the same city.

“Surface Tension” is only 9 minutes long and explores the way in which cinema can penetrate the essence of the moment and the essence of life, like his great contemporary, Jonas Mekas. The relationship between the architectonic monster that is New York and its role in space and time, its beauty, is like a brief glimpse against the eternity of time.

Frampton explores it with a frenetic run through at street level. It is a tribute to the western way of building technological cathedrals in the deserts with millions of people swarming at the feet of giants. The people and the buildings create a frenetic hyperreal universe that Frampton observes with its non-stopping camera. Everything is accelerated in modernity; even the camera has to accelerate to capture architecture in a way that transmits the reinvigorating effect of technology lunging forward.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.