5. The Descent (2006)

After a terrible tragedy costing her a husband, a daughter, and her mental health, Sarah assembles the squad to skip yoga class and descend down a God-forbidden cave filled with claustrophobic camera placement, with terrible lurking and screaming and biting monsters. Eventually, the lurkers attack the unfortunate women and survival seems to be the primal task for all humans involved – at least up until the end.

Last Frame’s Importance: After taking care of personal female business, and hallucinating an escape at blinding daylight that never truly comes, Sarah wakes up back in the cave, next to her giant torch lighting her face. Only to her distorted state of viewing reality, the torch is her daughter’s candlelights, lit for her special birthday occasion.

It is not unusual for the girl to appear throughout the film and depict Sarah’s damaged psyche, nor is it unusual for her to instantly disappear, as she does right at the moment the camera moves away from her. What is new, and terrifying, however, is that as the camera steadily moves away from Sarah too, we hear the creatures shrieking louder than ever – only they, too, are not seen anywhere near.

Sarah is left alone, all her friends killed, all the “monsters” loose, with the imagination of her daughter staying lit along the torchlight. I wouldn’t want to trigger any too tragic assumptions, but apart from contemporary thrillers’ choice to parallel the depicted demons with the heroes’ personal struggle, we do see Sarah’s capability of slaughtering a friend, only minutes before this haunting last frame.

Whether this is the nihilistic ending of a horror movie and its (now proudly surviving, even at the expense of her mental health) heroine, or the clue for an extreme sports trip gone bloody terribly wrong, one cannot shake that final shriek flying over lonely Sarah’s general shot.

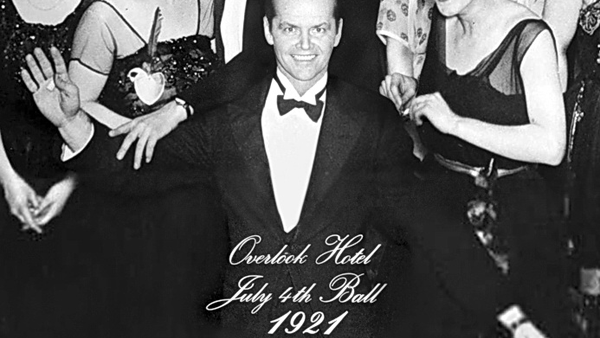

4. The Shining (1980)

A nice husband and father is slowly transformed into a Trojan horse for evil entities inside a huge Colorado hotel filled with atmospheric flashbacks, intentions of powerfully disguising any typical horror stereotypes present, and Stephen King’s voice echoing about his most (famously) hated adaptation of one of the books he wrote.

Last Frame’s Importance: All of our heroes are safe (well, almost all – wink at the aforementioned stereotype). The hotel is left alone with its terrible nightmares. And we slowly dissolve into a nice black-and-white memorial photo from one of the hotel’s festivities, dated back in 1929.

And wait, could this be our hero, Jack Torrance, that’s seen depicted among the happy crowd? Unable and unwilling to refuse the deliberate call for post-credits speculation and theories, we’re left to wonder: was the father’s spirit always a part of the hotel? Is he an incarnation? Is he the newest addition to this terrifying chess table of spirits? And who is Johnny?

3. The Mist (2007)

A Stephen King fatherly figure, having gone closer toward the right direction, tries to save his son and the few people non-intoxicated by the words and aphorisms of a “the-end-is-neigh” Marcia Gay Harden, while bloodthirsty creatures emerge from a mist surrounding the supermarket where the film takes place. Will help ever arrive?

Last Frame’s Importance: It never does, and in a rare moment of devotion to other people’s need for peace, the father is killing the only characters left alive inside a character (including his elementary school son), according to their own will and acknowledgment of the situation. The last bullet is saved, coming of course along with the last surprise.

Just as he’s about to take his own life, the military arrives to help the situation. And there’s no one left to celebrate the joyous moment with him. Ouch.

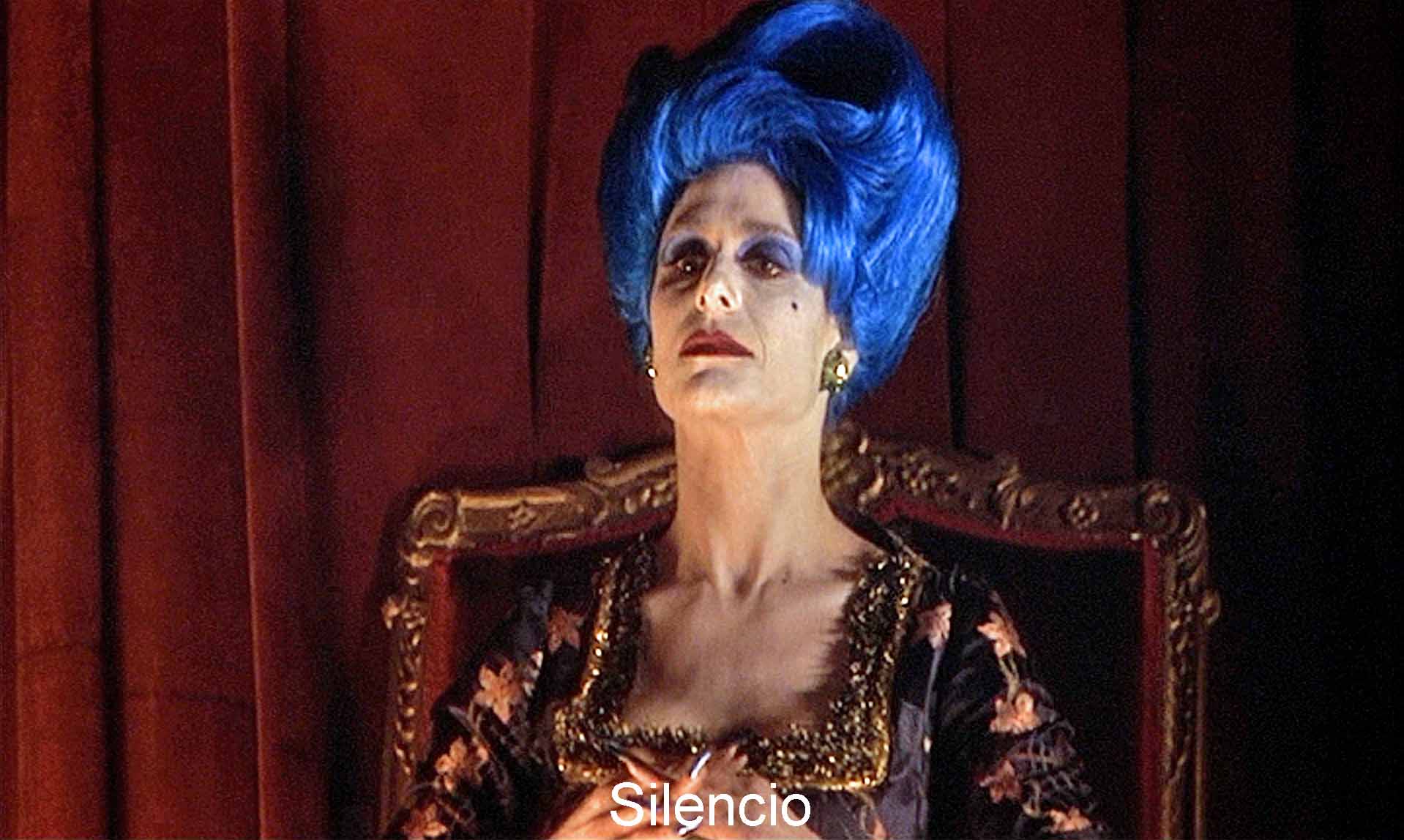

2. Mulholland Drive (2001)

Worlds within worlds, dreams within reality, blue within red, and a whole dreamworld trapped within a blue box are not even a third of what one experiences as he watches David Lynch’s greatest film to date. All that’s linearly important is that we’re following Betty on her quest to help a woman temporarily named Rita find who she is. The rest is rust and stardust.

Last Frame’s Importance: Every frame seems to hold a certain key, and only few resemble the accordingly awaited doors. But few shots could make us wonder more in fright, finding ourselves within the lunatic labyrinth Lynch trapped us, than the final shot.

A woman with blue hair, only present in club Silencio during a heartbreaking voiceover’d Los Angeles performance (not quite the rarity you’ll say), completely irrelevant to the whole plot, whispers to us something as we see her tired on her chair, on the lonely stage of club Silencio, after the terrifying discovery about the protagonists’ relationship, choices, and final fates.

We are left wondering who this lady is, with whom she could be connected, and why she’s asking us what she’s asking us. There are no answers, only questions in the place of other questions, and the rest is… Silencio.

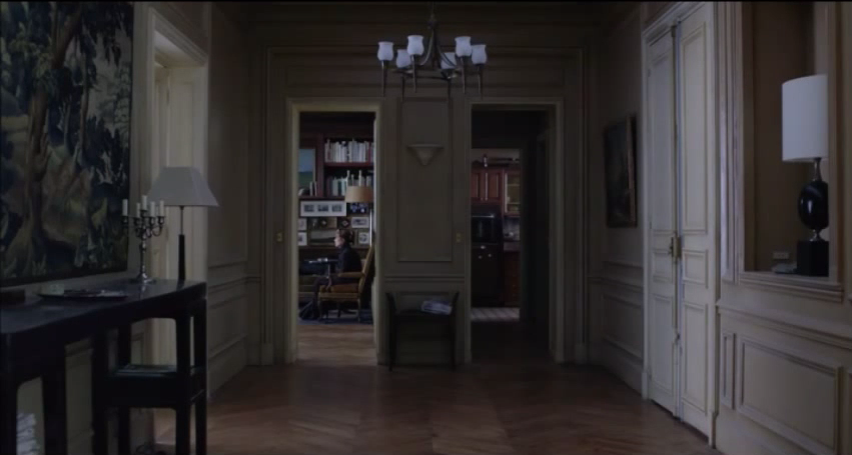

1. Amour (2012)

An octogenarian couple is faced with the most difficult task of their whole joint lives, which is to be dealt with by the husband alone. The woman has a potent stroke and her consciousness slowly slips away from her.

Love and death are themes whose boundaries seem more interwoven than ever in this masterpiece by Michael Haneke, and it is the excellent couple that carry us through the film’s two-hour journey, which, to them, is but the conclusion of their lifetime journey.

Last Frame’s Importance: We’ve already seen that love is the meaning, through the couple’s eyes and efforts, and yet the film decides to put the burden of importance elsewhere, putting a cherry on top of the cake, rather than a pin.

After a beautiful scene where the couple leaves their apartment the way they would to go to the theater (and watch… us, as implied by the equally potent first frame of the film), only to head for the afterlife.

We see their daughter; a character not really occupying the scene, but given enough space if one considers that the film’s whole plot merely involves the couple handling their final issues.

Isabelle Huppert, as the daughter, was constantly grinning about real estate through the duration of the film, and in general being the usual unloving relative who’s more occupied with their heritage than with her parents themselves. Now she is left alone in the living room.

Following her rationale from the film’s preceding events, she finally got what she wanted. The house is there, all quiet, all empty, all hers, and she could never be less grateful about it.

Author Bio: Leonidas Vyzas is a Law student who somehow managed to start studying Film Direction. Right now he is about to live for half a year in Bergen, Norway. He prefers being a film director than a lawyer for film directors, and would love making a documentary about the most interesting people (and foods) of his life.