5. The Lone Ranger

“Your expectations of how bad ‘The Lone Ranger’ is can’t trump the reality. The wild, wild West is actually more of a thundering bore than it was in 1999’s Will Smith fiasco, ‘Wild Wild West’.”

– Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

Another huge Disney flop and probably the most controversial entry on this list, “The Lone Ranger” is one of the long list of flops from Johnny Depp, whose success the studio only seemed to be able to capitalize on if he plays Jack Sparrow, who’s coming back yet again next year, even if none of the “Pirates” sequels can come close to the original.

The studio naturally thought they had another blockbuster on their hand, with both Gore Verbinski (director of the first “Pirates” trilogy) and Depp teaming up again to helm a family adventure picture. This time the film wasn’t going to be based on an amusement park ride, but on the classic radio show of the 1930s, which was also a popular TV show that ran in the 40s and 50s, “The Lone Ranger”.

Armie Hammer, who received acclaim for his double turn in “The Social Network”, dons the mask as the titular hero. Hammer does a noble job and certainly looks the part, but is completely played away by Depp’s (albeit controversial) turn as Tonto.

Much has been written about Depp playing the part of Tonto. In this day and age, the desire for more diversity shines through both in TV and film (just look at the cast of the upcoming “Star Wars” film), and this is certainly a good thing. Depp, however, fuses a lot of his comic timing to the character and the sense of sincere pathos that stops the character from becoming a caricature.

It should be no surprise that the film heavily differs from its original breezy creation. The sense of innocence is naturally gone and blood does indeed flow. The silly villains from the original are replaced by a cannibalistic outlaw (William Fichtner), an evil railroad tycoon (Tom Wilkinson), and a corrupt cavalry soldier (Barry Pepper).

Instead of the heroic duo seeking justice, the pair not only seek justice in the film but also vengeance as Fichtner’s character is culpable in the brutal slaying of the Ranger’s brother, and Wilkinson’s character slaughtered Tonto’s entire tribe.

Some of the criticism lays in the violence that some deemed excessive for this picture, but to Verbinski’s credit, the film never really feels uneven. All the action seems justified and he perfectly balances the heavy scenes with the breezy scenes. You get the sense that the aim was to make a simple entertaining adventure romp in the West and with that, it does succeed.

Maybe it was Depp’s overexposure (as well as him playing a Native American) that caused many people to be turned off by the picture. Maybe the filmmakers should have thought smaller, pouring so much money into a Western, a genre that rarely reaches the massive audiences they were obviously hoping for (though the latest remake of “The Magnificent Seven” has done quite well).

There’s also a sense that people refused to give this film a chance from the get-go. It either had to go beyond people’s expectations or fail miserably, and when it was just a simple entertaining action romp, people coldly dismissed it.

That’s a shame because there’s so much to enjoy in this film, from the humor, the fantastic production design (seeing a Western with a huge budget is always a lot of fun), to amazing action set pieces, particularly the final one with the theme music in the background. We have the Lone Ranger riding on top of a train with bullets flying everywhere, Tonto on another train dodging bullets with his idiosyncratic lapses; it’s absolute craziness that deserves more respect.

4. Lolita

“…Alas, his Lolita, with its distant earnestness and leisurely pace, might as well have been a Merchant Ivory production.”

– Michael Dequina, The Movie Report

As most film buffs know, Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial (and seemingly unfilmable) novel was adapted to the big screen back in 1962 by the one and only Stanley Kubrick. The film’s screenplay was written by Nabokov himself, but underwent drastic revisions during production. Not only did Kubrick change the order of events, but much of its content was altered to satisfy the strict censorship at the time.

There was no rating system then and its adult material was supervised by the Hays Commission, which was guided by Catholic principles. That the film was destined to be controversial isn’t wholly surprising, since the novel still packs quite an uncomfortable punch, with its main character being an unrepentant pedophile.

The original film, for all its technical wizardry from Kubrick, is thus a rather neutered version of Nabokov’s novel and Kubrick’s own vision. One of the censor requests was to change the character of Lolita from 12 to 14. Young actress Sue Lyon was chosen to be Lolita because the size of her breasts made her seem older, more like a woman and less like a child.

Nabokov would eventually confess that he felt that writing the screenplay was a taste of time, but upon seeing the film in a special screening that Kubrick arranged for him, he had nothing but praise for the cast and its infamous director.

Thirty years later, another adaptation hit the big screen with Adrian Lyne in the director’s chair. The screenplay was written by Stephen Schiff, who was hired to write the screenplay after several earlier drafts from notorious writers such as Harold Pinter and David Mamet were rejected. With the Hays Commission long gone, the screenplay and the eventual film became much more faithful to the original novel, which inevitably sparked some controversy at its release.

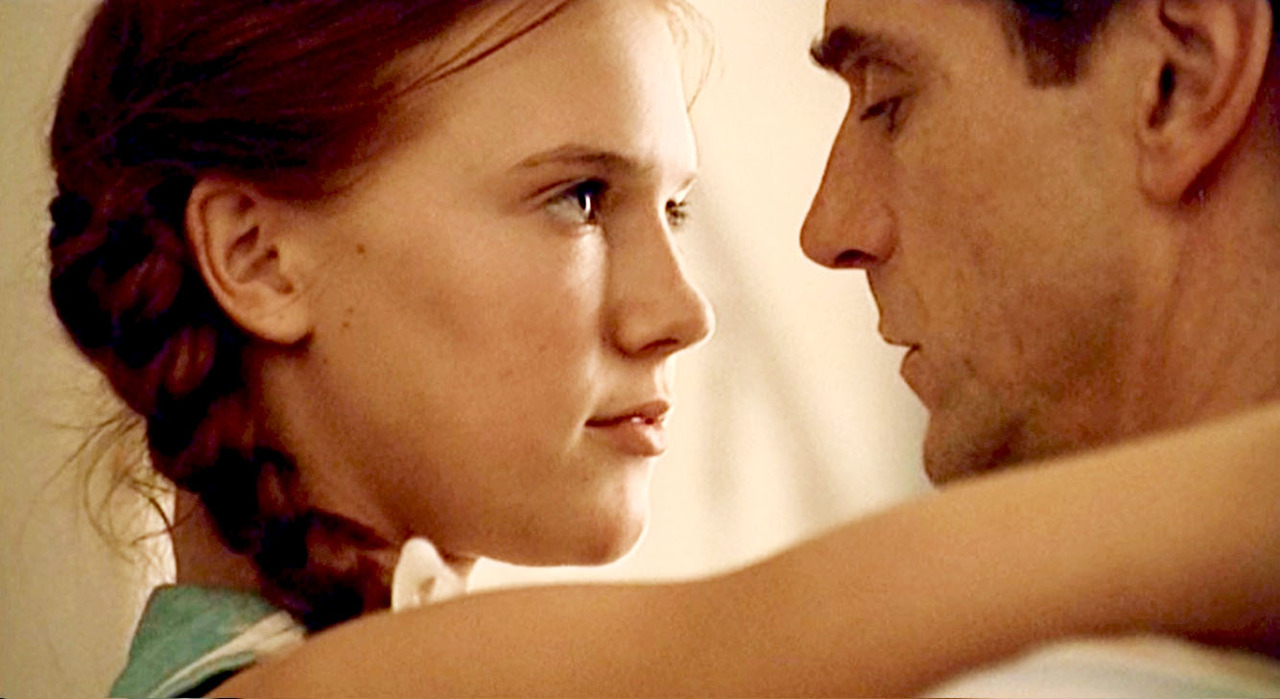

However, Lolita still remained 14 in the film, and the 12-year-old Lolita would remain in the novel. Lolita would be played by Dominique Swain, who was 15 at the time. The young actress perfectly imbues the youthfulness that makes Humbert’s obsessive love both creepy and somewhat endearing.

There is one major difference between the novel and the film that is worth pointing out; the love that Humbert has for Lolita seems genuine in the film, however tragically misguided.

Even though one could argue that the story is told through an unreliable (and sick) narrator, his affection for her seems to spawn from something pure, something transcendent. In the novel, however, told via a long confession in a prison cell, Humbert comes to realize that he’s robbed Lolita of her childhood, his guilt extended even more when he hears children playing outdoors.

This difference might be troubling for Nabokov’s purists, but it doesn’t change the incredible job that Lyne did with the screenplay. Lyne’s filmography tends to be very uneven (with gems like “Jacob’s Ladder” but also uninspired drivel like “Unfaithful”), but “Lolita” is a near masterclass, overshadowed only by its original adaptation, which was in the hands of the one of the world’s greatest filmmakers.

Lyne takes a few cues from Kubrick’s original vision, such as extending the role of Clare Quilty, which was played by Peter Sellers in the original vision. Sellers did a marvelous job in the original and completely stole the show, prompting James Mason to regret not campaigning for the part.

Frank Langella, however, is just as good, and his take on the character is much more ominous. His introductory scene is especially one of the most memorable scenes in the film, sitting outside on a porch asking Humbert questions in the shadows, sparks of electricity illuminating his face from light to darkness as flies are electrocuted by a hanging fly-trap.

You just know this guy is dangerous, his evil near supernatural levels, obviously perceived through Humbert’s own fear of what this man can take away from him. Their final confrontation is even better than the Mason/Sellers version; filled with madness and blackly comical, with a drugged-out Quilty flailing his arms wearing only a robe, and yes, Langella bears all.

Together with another beautiful moving score by Ennio Morricone, Lyne’s “Lolita” is severely underrated but tasteful, with three masterful performances from Irons, Swain, and Langella. Even if it lacks Kubrick’s masterful composition, Lyne imbues the film with his own style, its colors radiant and dreamlike; it all seems like a beautiful dream from which Humbert inevitably had to wake up, and then it turns into a nightmare.

3. Cowboys & Aliens

“Daniel Craig and Harrison Ford contend with goo-dripping aliens in Jon Favreau’s sadly humourless sci-fi western.”

– Philip French, The Guardian

Jon Favreau helmed quite a few significant blockbusters, from starting the Marvel Universe with “Iron Man” to his live-action remake of “The Jungle Book”, and soon a live-action remake of “The Lion King” will be released with his name. From a guy that started with “Swingers”, a small independent film, he’s gone far.

Favreau seems a deft hand for quality commercial blockbusters, giving the audience all the silly action set pieces but never for the sake of the story (though “Iron Man 2” might be a slight exception, but there was a lot of rush going on behind the scenes), and giving characters enough character development to give his films some class. They aren’t necessary high-art, but Favreau respects his audience, unlike the guy who made all those “Transformers” movies.

Favreau’s balancing act does wonders for “Cowboys & Aliens”, a film that was a flop at the box office (and in its first week, stood second to “The Smurfs”). It barely made back its budget and seemed like more proof that big-budget Westerns are box office poison. However, as you can see from the title, the film is not just a Western; there are also aliens in this film.

Based off of a graphic novel, you’d expect the film to be rather silly, merely B-movie fun but with a bigger budget. Instead, the film takes a more serious approach, yet it never skims from the fun. Strangely, the film was criticized for this, as you can see from the above quote.

The film could have easily veered into parody, with characters making postmodern references, but that’s the greatness of this film; the characters are real, dirty, gritty, full of old-school wisdom, and none of them feel cartoonish. They are up against something they do not understand, but they consider it their duty to save their loved ones, no matter what demons they have to face. It’s this surprising adult approach that makes this film stand above the various other blockbusters of its time.

The film opens with a loner (Daniel Craig) waking up in the desert with a strange metal device stuck to his hand. Wandering into the town of Absolution, he catches the eye of Sheriff Taggart (Keith Carradine), who recognizes him as a wanted outlaw. After a big scuffle, Taggart manages to arrest him along with an annoying drunk, Percy (Paul Dano).

However, Percy’s father, cattleman Dolarhyde (Harrison Ford), demands Percy to be released and wants the loner for himself because he believes he stole gold from him. That night, however, an alien spacecraft appears, kidnapping several of the town folk. The loner, known as Jake Lonergan, manages to shoot one of the spacecrafts with the metal device stuck to his hand. Seeing this, they know that they need Jake to defeat the aliens and save their loved ones.

The two main stars, Craig and Ford, do a reliable job. Craig is his usual cool self, though you can’t help but see James Bond anytime he appears. Ford seems a great fit for the Western genre, talking with a gruff voice and having no problem stepping back whenever Craig needs to be the definite hero of the picture

. It’s the supporting cast, however, that really makes this film work, with Clancy Brown as the wise and noble preacher; the always fantastic Sam Rockwell as the somewhat cowardly but eventually heroic saloon owner; Keith Carradine returning to the Western genre after his brief but great performance in “Deadwood”; the lovely Olivia Wilde as Ella Swenson, a woman with a secret; and even the great Walton Goggins as a bandit.

The film, with its loads of CGI, does feel like a gritty Western, and it’s obvious that Favreau harbors a lot of love for the genre.

2. The Cotton Club

“Given its garish production history, one rather expected ‘The Cotton Club’ to sing with hot-jazz desperation. Instead, we get the mediocre craftsmanship of a pit band in Vegas.”

– Richard Corliss

Most film buffs know that Francis Ford Coppola has quite the history with troubled film productions. Everyone knows the legendary tales that went on behind the scenes of “Apocalypse Now”; its star suffering alcoholism and an eventual heart attack, a paunchy and unprepared Marlon Brando wreaking havoc on set, rampant drug use by the cast and crew, and that one incident where real corpses were almost used as props. The filming of “The Cotton Club” was luckily not as dramatic, but Coppola’s high ambition did get him into hot water with producer Robert Evans.

Coppola had taken on the job as director to pay off some incredible debt, after the critical and commercial bomb that was “One From the Heart”. “The Cotton Club” would suffer a similar fate (though it would receive better reviews, one especially lauding one from Roger Ebert), and Evans blamed this solely on Coppola, stating that it was his doing that made the budget escalate so dramatically.

There is surely some blame to be put on the legendary director; he had fired Evans’ crew and hired his own, as an example. Yet, if one were to look deep enough into its production, there is certainly a case to be made that Evans’ own troubled personality is equally guilty of its problems.

The film was a dream project by Evans who not only wanted to produce the film, but wanted to direct it as well. Evans struggled the find the necessary means for its production, but finally received backings from two Las Vegas casino owners, an Arab arms dealer and vaudeville promoter Roy Radin.

The latter backer would prove especially struggling, as Radin would be murdered due to his financial disagreements with drug dealer Karen Greenberger. She had introduced Radin to Evans and wanted a fair share of the profits, but Radin only offered her a hefty finder’s fee, which, compared to Evans and Radin owning 45 percent of the film, she found deeply unsatisfactory. Evans would have nothing to do with his murder, but would become implicated in the investigation.

At the last minute, Evans decided to not take on directing duties and asked Coppola instead. Richard Sylbert, the production designer of the film, had written letters to Coppola, warning him of Evans’ mental state. According to Coppola, “Evans set the tone for the level of extravagance long before I got there.”

Coppola’s improvisation approach to the actors, the delays it caused in filming, and the results of script changes caused him to butt heads with Evans during filming, and soon enough Coppola barred him from the set. The script itself was written by the great Mario Puzo, but he wasn’t the only great writer involved with the script; Pulitzer Prize winner William Kennedy was brought on to polish the script, and eventually turned in 20 drafts of it.

With all of these messes behind the scenes, it’s all the more logical to expect the film to be a giant mess as well. Its troubled production was already known at the time, causing the film to be received unfairly, even giving Coppola a most unwarranted Razzie award. Looking at it now, it’s a supremely entertaining, beautiful looking gangster epic. Taking place in 1930’s Harlem, it’s overflowing both with remorse for the sins of its time, but also with its love of tap-dancing, swinging style, the purity long gone with the excesses of today.

The film follows multiple storylines that all converge around the Cotton Club; Dixie Dyer (Richard Gere) is a broguish trumpet player who saves the life of Dutch Schultz (James Remar) from an assassination attempt. In turn, the grateful Schultz hires him as a musician and as a chaperone for his goomah Vera (Diane Lane), who Dixie begins to fall for. Dixie’s brother Vincent (Nicolas Cage) gets hired as a henchman by Dutch, but soon becomes disillusioned by his treatment.

Meanwhile, the Cotton Club’s owner Owney Madden (Bob Hoskins) and his right-hand man Frenchie (Fred Gwynne) try to control the increasingly unhinged Dutch, who starts a war with Harlem gangsters. One of the dancers of the Cotton Club, Delbert ”Sandman” Williams (Gregory Hines), has a love affair with Lila Rose Oliver (Lonette McKee), but their love affair becomes strained with the race relations of the time.

There’s hardly an unfamiliar face among its cast; we have Laurence Fishburne (known then as Larry) as Bumpy Rhodes (whose character was based on Bumpy Johnson, a character he would portray in “Hoodlum”); Julian Beck as Dutch’s right-hand man Sol Weinstein; Tom Waits as Irvin Beck, a presenter at the Cotton Club; Jennifer Grey as Vincent’s wife; Diane Venora as Gloria Swanson; Joe Dallesandro as Lucky Luciano; and we even have appearances of Mario Van Peebles, Bill Cobbs, Giancarlo Esposito, Mark Margolis, and Ed O’ Ross (who in turn would become the assassin of Dutch in “Hoodlum”). The greatest standouts, however, are Bob Hoskins and Fred Gwynne, who star in the best scene of the film.

The characters they play were close friends in real life, as they are in this film, and in one particular scene, after Frenchie is rescued from being kidnapped and reunited with Owney, we see how much they care for each other. This scene in particular is both touching and funny, endearing and unforgettable – you wish we would get a whole separate movie about just these two characters.

Probably the biggest flaw of the film is the length; the film is just two hours and could have been much longer, especially with its large cast. You do get a sense that several characters have much more importance in the longer cut, which is probably owned by Coppola. One hopes that maybe one day we will see this longer cut, but the chances of this are very small, especially with the troubling production in the background.

And that’s a shame, because it would be wonderful to see more of this world and its characters. The film has a beautiful and triumphant ending, and there’s almost a sense of sadness. We wish we didn’t have to say goodbye but eventually we have to. Time moves on. This town will never look the same again, but that’s the magic of cinema, because unlike our history, we can always go back and relive the spectacle all over again.

1. Dredd

“In a world of compromised adaptations, ‘Dredd’ is something of a triumph.”

– Phelim O’Neill, The Guardian

The British comic anthology “2000 AD” has been criminally ignored by Hollywood. The long-running series, spanning more than four decades already, is filled with cinematic potential just waiting to be explored by some visionary filmmaker and a brave studio executive.

You’d think in this overkill of comic adaptations that more of its strange characters would have hit the big screen. Alas, like many of its peers, if it doesn’t involve guys in suits beating the hell out of each other or some subversion of the superhero genre, it won’t get as much attention.

Many of the “2000 AD” characters have received cult followings that are large enough to be significant, but too small to pique the interest of Hollywood. One of the characters that has, so far, received cinematic treatment is its most popular character, Judge Dredd. The character itself was a critique on the American anti-hero as well as the time of when its creators (John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra) lived in; the dawn of Thatcherism, the rise of laissez-faire capitalism.

The comic was an apocalyptic pulp but one that’s also steeped in social commentary. There was brutal violence (its character would also inspire “Robocop”), it had robots and ghosts, and it was both wacky and serious. Grim times call for grim characters, and the character of Judge Dredd perfectly personified the time and beyond; authoritarianism will always be there, and human beings will keep messing it up. There will always be a Judge Dredd somewhere in the world.

The first adaptation would become 1995’s “Judge Dredd”. It starred Sylvester Stallone as the titular character and as you can probably guess (if you haven’t seen it already), it would have none of the spirit of the comic. The production started innocently enough, even hiring an English director who was a fan of the comic, but it soon turned into another run-of-the-mill Stallone movie. The character deserved a star without a huge ego and Stallone is not one of them.

On the surface, the film looks like a proper Dredd film; the production design has to be admired, as well as some of the character designs, but it has none of the spirit or tone. It might have had brutal violence but it also had horrible puns. You have talent like Max von Sydow as a aging judge, but you also have Rob Schneider as Dredd’s buddy sidekick.

Stallone might look like Dredd in some of the scenes, but he also takes off his helmet, a mortal sin for all Dredd fans. Not to mention that almost everybody has seen some edit of Stallone and his co-star Armand Assante on YouTube hamming it up, screaming about THE LAW. The film seemed to have ruined any chances to see Cursed Earth on screen again.

That was until 2012, when “Dredd” came blasting through the screen. The screenplay was penned by infamous writer Alex Garland (famous for his extraordinary penmanship with “Sunshine” and the recent “Ex Machina”, which he also directed), and his love for the character can be clearly seen.

With the budget being restricted (at least in Hollywood terms), Garland couldn’t make it a grand epic, and had to write a smaller story that would introduce the Judge and the sordid world where he lives. In quick narration by the infamous Judge himself (Karl Urban), we are told about the Cursed Earth, the irradiated wasteland, and Mega-City One, the last bit of civilization left in America.

In order to make some attempt at managing the violent crimes, there are Judges; a law-enforcement that acts as judge, jury, and executioner. From the beginning, we already get a sense of how hopeless it is; of the 17,000 crimes reported daily, only six percent of this can be responded to, not to mention the fact that the lifespan of a Judge doesn’t tend to be long.

The Chief Judge (Rakie Ayola) takes an interest in trainee Anderson (Olivia Thirlby), who has psychic powers but has also failed her aptitude test. She assigns her to Dredd to see if she’s qualified, knowing she could be an asset to their cause. Dredd and Anderson respond to a call from Peach Trees, a 200-storey tower block run by a drug lord known as Ma-Ma (Lena Headey).

The call concerns the skinless bodies of three drug dealers, which have been dumped from high above the tower. In their investigation, Dredd and Anderson arrest Ma-Ma’s associate Kay (Wood Harris). Naturally, Ma-Ma can’t let this happen, and seals off the tower block and sends a herd of men to kill the judges.

“Dredd” is a film that gets better and better with repeated viewings. While it may miss some of the social commentary that “Robocop” had, “Dredd” comes extremely close to Paul Verhoeven’s 80’s classic. But even that is unfair, since “Dredd” has its own style.

It might have extreme violence that borders on the darkly comic, just like “Robocop”, but there are times when it looks beautiful, even when it becomes extremely gory. The soundtrack switches from pumping synth to this dreamlike echo, which perfectly portrays the madness of what’s going on, not only on the screen but in the mind of its characters.

“Dredd” mostly takes place in the apartment complex of Peach Trees and we see little of the world of Mega-City One. Obviously, the point was that the film would make enough money to warrant a sequel, but this was sadly not the case. “Dredd” is only a glimpse, but a powerful glimpse of what an incredible franchise it would have been. The film has gained notoriety in time, with many fans trying to petition for a sequel or even a Netflix show, but so far nothing has been confirmed.

Urban has addressed his desire to don the helmet again, being a huge fan of the source material. Unlike Stallone, he was such a fan of the material that he said that he wouldn’t have even bothered if he read the script ”and found scenes where Dredd removed his helmet,” saying that it’s not the ”Dredd I grew up reading and admiring.” Now that’s a true fan.

Whether or not we will ever see a sequel (and let’s hope we do), Urban will be one version of Dredd that both new and old fans will grow up to and admire.

Author Bio: Chris van Dijk is a writer and a self-proclaimed cinematic-connoisseur who started his unhealthy obsession with film at a very young age. He’s famous for being an incredible slob, taking himself way too seriously and getting along brilliantly with anyone who agrees with him.