Sound, unlike the image, doesn’t force itself upon you. It very rarely forces any perspective; you are free to explore auditory stimulus without intervention by the artist – who’s constantly shifting your view, and limiting your focus.

At least, that’s the image it’s given itself. The beauty of sound comes from the way filmmakers have used it: if you don’t know how to create good sound design, you don’t bother.

Thus, sound has been spared from the hordes of disastrously meaningless directors hoping for a quick penny. Silence is sound’s eloquent counterpart, and plays an equal role is the auditory element of filmmaking. This is a list of ten films which use silence in a powerful and inventive way.

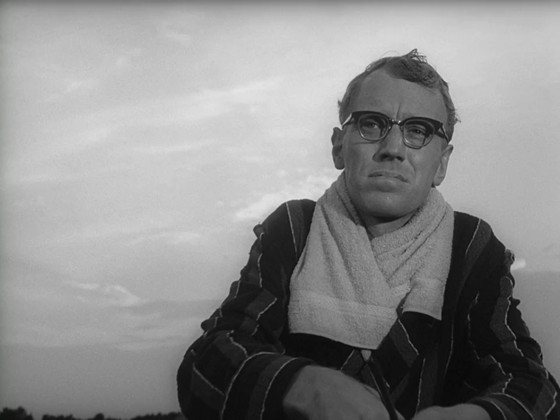

1. Through A Glass Darkly (Dir. Ingmar Bergman)

Young Karin has just been omitted from a mental hospital; her mind appears to be splitting in two, each half trying to stay grounded on a different plane of existence. Ingmar Bergman offers two sides of the same spiritual coin: one side in reality – love, silence, family – the other side disassociated, and seemingly un-fated – God, music, sex.

When broken into these two halves, each of the themes is tightly interwoven with its companions. Bergman links music, sex and dissociation (which is already established as related to Karin’s psychosis, as is that to God and her visions of Him) in one incestuous and sensual scene.

In this scene, Karin has just run to a small ship wreck, a few metres off the coast of the island, and huddles in psychotic fear of an approaching storm. Her younger brother Minus comes to comfort her, and she offers herself to him; the rain falls, loudly; then Sarabande from Bach’s Suite No. 2 begins to play. The audience is left wondering.

Silence plays a counter role in a later scene which Karin. After returning to the room in which “someone called [her] from behind the wallpaper”, Karin talks to the wall, taking long pauses to allow time for a response – which no one can hear, say for her. After this episode, she confesses to having “seen God”, before she is taken back to the hospital.

As an audience we do not hear the words of this spirit – we hear the silence of reality – therefore we are not told of God’s coming, as Karin is. We see her family and hear their love for her, yet we are devoid of God in the way she sees Him; we are left with only love. But, as Karin’s father questions in the very next scene: is love God himself?

Bergman ties such tight and intricate knots; every element of his films culminates into an eloquent thesis on the human condition. And, in Through a Glass Darkly, sonic artists Staffan Dalin and Stig Flodin play an important role in developing his thesis.

2. Nostalghia (Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky)

Tarkovsky’s first film outside of the Soviet Union, unsurprisingly, explores themes of loneliness and isolation.

The Russian writer Andrei Gorchakov is in Italy to research the life of eighteenth-century poet Pavel Sosnovsky; Andrei is deep in the Tuscan countryside, with his translator Eugenia; the morning after their arrival we meet Domenico. Domenico is seen as a madman for keeping his wife and children locked in his home for seven years, for fear of a biblical apocalypse.

Andrei feels an immediate affinity for Domenico. Andrei convinces Eugenia to take him to Domenico’s home, where he asks her to start a conversation with him. She fails, but Andrei pushes her to persist – as he believes his poor Italian will inhibit him from having any meaningful conversation.

“My subject is a Russian who is thoroughly disorientated by the impressions crowding in upon him, and at the same time about his tragic inability to share these impressions … I myself went through something similar when I had been away from home for some time”

– Andrei Tarkovsky (Sculpting in Time, 1986)

At this point in the film Tarkovsky seems to offer himself a piece of optimism: after Eugenia fails to converse with Domenico, Andrei – in his broken Italian – sparks a passion in Domenico and is invited into his home. A silent communication is established and together they transcend the language barrier – something which Tarkovsky’s visual poetry so easily does.

Though this metaphorical silence displays an optimistic side to Tarkovsky’s nostalgic anxiety, the film as a whole seems to paint a more unsettling picture of life as an outsider. Andrei, all the while he’s in Italy, appears to lack confidence and inspiration; he appears “crushed by the recollections of his past … which assail his memory together with the sounds and smells of home”. His inspiration seems to be at home in Russia, along with his family.

The majority of natural sound, non-dialogue sound, arrives in the form of Andrei’s dreams – for, when in Italy, Andrei is at the mercy of verbal communication. This leads to an incredibly quiet first act.

The silence of nature becomes most striking after Andrei’s first dream sequence: the rain falls heavily as he drifts into a slumber, and slowly subsides to silence as he enters his dream; once in the dream, an inexplicable trickling arises and does not subside until he’s woken.

In the next scene, Andrei and Eugenia walk and by a pool, in which people are bathing, yet no sound is emitted from the water. This contrast is also present as Andrei’s relationship is first sparked with Domenico: Domenico plays a record of Beethoven’s Ninth, and exclaims “Did you hear that? It’s Beethoven!”.

This suggests the kinship offers Andrei a kind of inspiration or, at least, a motivation. And, after Domenico’s passing – in a ball of fire, a scream of pain, and to the Ode to Joy section of Beethoven’s Ninth – Andrei’s final quest for spirituality is in silence, right before he tumbles into a dream filled with the sounds of Russian folk music – and is reunited with his homeland, and its artistic riches.

3. I’m Not There (Dir. Todd Haynes)

Bob Dylan is a musical legend. He’s inspired a great number of brilliant musicians – and an uncountable number of terrible ones, myself included. Todd Haynes’ portrait of Dylan, captures this inspirational tone in a most cunning way: even in the scenes in which Dylan’s embodying character – for there are six/seven different Dylans in the film – is in excruciating pain, or cringing embarrassment, there’s still a sense of heroism in what he’s doing.

This, in itself, is much like the feeling which arises when listening to some of Dylan’s own music – he whines so violently, about such heart-breaking issues, it sounds like he’ll shatter his own eardrums and deafen himself to the world’s ailments.

The soundtrack is brilliant. Haynes flows seamlessly between Dylan’s earlier ‘protest’ recordings, right into his later work – including an excellent performance of ‘Pressing On’, from his gospel-esque album ‘Saved’.

It would’ve been so easy for Haynes to assemble a soundtrack which told the story well enough, then accompany that with some beautiful visual metaphors that reiterate those ideas. However, he makes a conscious effort to say something about Dylan which his music hasn’t already said more eloquently.

The role of silence becomes incredibly important towards the end of the film; the strategic placement of these pauses doesn’t just hint towards a kind of creative interlude, but gives a chance for the audience to realise that we’re peeking into the life of a real person – not just some music video caricature.

Nowhere is this clearer than in one completely silent shot, during a montage sequence covering the divorce of Robbie Clarke – a version of Dylan – and Claire, his young love. The shot is of their first meeting, in a Greenwich Village café. The silence is non-diegetic, and Claire appears to utter some words, though they go unheard.

This disassociating silence creates a sense of distance between the audience and the characters, which is incredibly powerful when contrasted with the way in which Haynes – from the beginning of the film – has been using Dylan’s music as a way of placing you inside his head. You are now an onlooker; you’re looking directly into his life.

4. Stalker (Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky)

Stalker is, perhaps, Tarkovsky’s most searing social commentary. Not only does it criticise the Soviet Union’s secretive nuclear testing – and their general tendency to conceal information from their own people – but, at its most fatalistic, posits that: humanity is terrifyingly unaware of its own impurity.

The Room is a place where, legend has it, a person’s innermost wish will be granted. This Room attracts a mass of opportunists seeking to exploit it for their own gain, each of whom – those who make it through the surrounding Zone – is left dissatisfied when they find out what their innermost wish really is. The film follows the journey of a Professor, a Writer, and a Stalker – a person with a knowledge of the Zone – as they have their faith tested along its the winding paths, and again on the threshold of the Room.

Upon first entering the Zone, the frame is washed with colour; the scene goes from the sepia of the outside world, to the colours of edenic sanctuary. This is accompanied by a contemplative silence – in contrast to the indistinguishable metallic music and clanging railway cart. This moment of silence within the Zone is broken by Stalker exclaiming his joy at being “home” and saying: “There isn’t a soul here”, which is promptly contradicted by Writer, “But we are here!”

This appears to hint towards a lack of modesty within the characters; they – particularly Stalker – see that they are above other people, and that their presence is somehow different from anybody else’s, which is something they only thoroughly question once at the threshold of the Room.

At this point it’s worth mentioning, Tarkovsky deliberately removed any overtly alien references when adapting this film from Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic, which allows for more ambiguity around the power of the Room – which, in turn, makes exploring philosophical and religious concepts far easier.

Knowing Tarkovsky is inviting – defiantly not demanding – theological reflection, puts a certain weight on a moment of silence similar to the first. In this moment, the three men sit on the threshold of the Room, deliberating their entrance, a moment of silence falls. The camera tracks backwards into the Room.

Then Stalker utters “How quiet…” and the moment passes. This silence embodies the very dilemma they are having: can they truly have faith in the Room’s powers, without ever entering for themselves? The silence answers that question: faith ceases to be faith in the face of proof – as silence ceases to be silence when exclaimed upon.

5. Das Boot (Dir. Wolfgang Petersen)

You’re two-hundred metres below an enemy destroyer, your instruments are blown, your U-boat is rated to a maximum of ninety metres; water is spraying into the hull, and your men are wounded. Every moment of silence is a moment in which you’re not being bombed, your ship isn’t being crushed under the pressure, and your men aren’t screaming in agony.

Das Boot tells the story of a German U-boat and her crew; their mission is to harass and destroy British cargo ships. In short: this film takes on the daring task of stirring an empathy for Nazi soldiers, and it succeeds.

Personification plays a massive role in the power of this film – whether it’s re-personifying the caricatured villains of Nazi Germany, or breathing life into fifty tons of German war machine. The sweating of the crew, under the pressure of enemy attacks, meets the sweating leaks of the boat under two-hundred metres of cold Atlantic water; the moaning agony of the crew harmonises dreadfully with the moans of the boat.

At one crucial moment of the film, the role of silence becomes both narrative and emotional. After their most devastating attack, the crew spend fifteen hours – diegetic time, of course – making repairs to the boat.

This section of the film closes on a single shot which encompasses thirty-three seconds of near silence, directly after the captain receives the news that the final repairs have been made. The leaks have been stopped, the crew are sleeping, they’re no longer being attacked; there is safety, and there is silence.