20. Grandmother (Brillante Mendoza, 2009, Philippines)

Having directed 21 movies since 2005, Brillante Mendoza has come to symbolize Filipino cinema to the rest of the world. This particular film is one of the most distinct samples of his style.

Two elderly woman suffer from the same crime, although from completely opposite sides. Lola (the word Filipinos employ to address elderly women) Sepa’s grandson has been murdered over a mobile phone and she has to raise enough money for a proper funeral and see that justice is served. Lola Puring’s grandson is the perpetrator and currently in prison, and she has to raise money for his bail and defense by selling vegetables illegally in the streets.

Mendoza uses the case to portray life in a poor district in Manila, where the majority of the wooden houses hang barely above overflowing canals and the rain is constant. Using a hand-held camera, he shoots his scenes in an utmost realistic fashion, thus resulting in the film appearing similar to a documentary regarding the lives of the poor elderly women in the country. Furthermore, he stresses the significance of women in local society, a fact emphasized by the almost complete insignificance of men in the story.

Both of his protagonists, the 85-year-old Anita Linda as Sepa and 79-year-old Rustica Carpio as Puring, are impressive in their respective parts.

19. Departures (Yojiro Takita, 2008, Japan)

“Departures” is one of the most distinct Japanese movies of the 21st century, particularly due to the Oscar it won in 2009 for Best Foreign Language Film of the Year.

Daigo Kobayashi is a cellist whose orchestra disbands due to financial reasons. Subsequently, he decides along with his wife to move back to his birthplace to start over. While searching for work to no avail, he stumbles upon an advertisement for an employment regarding “assisting departures” and addresses it believing he will work in a travel agency.

However, after his visit to the office, he realizes that he is to work in a funeral home preparing bodies for cremation. He accepts reluctantly, and has to face the nausea the deceased individuals bring him, the scorn of his wife when he discloses his actual line of work, his hatred for his father, and his guilt for having abandoned his mother.

Takita pays a tribute to the dead, and particularly to the encoffinment technique, by surrounding the mystery with reverence and including it among the protagonists of the film. His direction capitalizes on the direction style of Ozu, with the slow pace, the scarce dialogue, the attention to detail and thus to realism. However, he enriches the film with contemporary elements, mainly the humor that appears in completely unexpected moments, in order to lighten the mood of the movie.

Furthermore, his message regarding hatred resulting from ignorance becomes quite evident through Dago’s feelings concerning his father.

The entire cast does a terrific job, with Masahiro Motoki and Tsutomu Sasaki truly excelling.

18. Pieta (Kim Ki duk, 2012, S. Korea)

Kim Ki Duk’s foremost-celebrated film bespeaks the ability of the Korean filmmakers to shoot masterpieces concerning the concept of revenge.

A young enforcer of a loan shark threatens and leads owners of miniscule technical shops into the slums of Seoul to self-mutilate, in order to pay the sums they owe from their insurance. Eventually he comes across a woman who alleges that she is his mother. In an utmost Kim Ki Duk concept, he rapes her before he accepts her in his life, which changes to a point where he cannot manage without her presence. However, when she is abducted, he has to search for her through the individual he tortured and at the same time to fight his own Erinyes.

Kim Ki Duk directs a film whose principal purpose was to shock its audience, and he achieves that with a number of onerous scenes and themes reminisced of a Greek tragedy: persecution, Oedipus complex, revenge, Erinyes, redemption and catharsis. Furthermore, as the film progresses, the pace becomes quicker and more intense, while he presents a number of unexpected occurrences, thus resulting in an agonizing thriller regarding a violent human confrontation instead of a grotesque art film.

17. Still Walking (Hirokazu Koreeda, 2008, Japan)

“Still Walking” is a distinct example of Japanese cinema, in both themes and technique, and is the one that established its director as the definite successor of Yasuhiro Ozu.

The son and daughter of the Yokoyama family return to their parents’ house in the country to commemorate the death of their brother, who accidentally drowned 15 years ago. The son, Ryota, has recently married a widow with a young son and has brought them along; the daughter, Chinami, has come along with her husband and their children. However, tensions that preexisted now move to the foreground.

Hirokazu Koreeda directs an ode to realism, a fact stressed by the tensions and the general feelings occurring between the members of the family, which are similar to the ones of every household. The camera use, which is situated extremely close to the set, makes the spectator feel as though he is present in the house where the movie occurs, participating in the discussions in the table and walking around with the protagonists.

Apart from the above, the pace is slow, the dialogues meaningful, the exaltation non-existent, the focus on detail great and the acting sublime, in a true Ozu fashion, however in contemporary terms.

16. Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2006, Thailand)

This autobiographical film is composed of two parts where the dialogue and characters are the same, but the setting and the outcome are different. Weerasethakul was inspired to create the two lead characters by his parents. However, the situations that appear in the film are based in fact, but on his interpretation of their lives before they became a couple.

In the first part, the protagonist is a female doctor and the story takes place in a hospital similar to the one where the director was born. The second part focuses on a male doctor and is situated in a contemporary Bangkok medical center, in a world similar to present-day.

The director explores the notion of memory and the way a number of seemingly insignificant occurrences can result in the happiness of an individual. Furthermore, in the world created by Weerasethakul, the shape of things and the essence of the environment define the characters’ emotional status.

In conclusion, this highly artistic film deals with the way individuals transform themselves for the better.

15. The Twilight Samurai (Yoji Yamada, 2002, Japan)

Seibei Iguchi is a low ranking samurai in 19th century Japan, who struggles to take care of his orphaned daughters and his senile mother. Because of this, apart from his bureaucratic duties, he also has to work in the fields, a notion that seems preposterous to the rest of the samurai who constantly mock him. However, his fate changes when Tomoe, his long-time love, reappears in his life, thus eventually resulting in a duel with her former husband and an order from his lord to kill a disowned samurai retainer.

Yamada directs a film with the utmost respect toward Japanese tradition. However, he additionally incorporates the sense of decay that characterized the end of the samurai era, where the ethics and notions that nurtured the class for centuries are gradually disappearing. The nostalgia toward that age and the resulting melancholy are omnipresent, even during joyful moments.

Hiroyuki Sanada is magnificent as the decaying samurai, in a movie that won the majority of the local awards including 12 by the Japanese Academy.

14. Confessions (Tetsuya Nakashima, 2010, Japan)

Based on the novel by Kanae Minato, “Confessions” deals with the tragic story of Yuko Moriguchi, a junior high school teacher. One morning in the classroom, after distributing milk to her students, she proceeds to inform them that this is her last day at school.

Two facts regarding this teacher were common knowledge, up to that point. Her husband is HIV positive and her daughter, who attended kindergarten, was drowned in the school’s swimming pool by accident. However, she discloses that her death was not an accident, but a murder, and the two perpetrators are presently in the classroom. She does not name them; nevertheless, she presents enough evidence for the rest of the class to not have doubts regarding the wrongdoers. Furthermore, she states that she has inserted blood from her husband inside the milk boxes of those two students, who have already consumed it.

Tetsuya Nakashima depicts the film mainly through flashbacks resulting from the confessions of the protagonists. Furthermore, he presents a number of social issues including sexuality, death and bullying, as well as the relationships between parents and children, between teachers and students, and between parents and teachers.

Another characteristic of the film is that the majority of the protagonists are drowning in their need for revenge, a notion that causes to the film’s audience to not be able to sympathize with any of them, despite the fact that they all are victims.

Equally impressive is the fact that he manages to provide humor, however cruel and dark, in a cold, psychological thriller.

13. I Saw the Devil (Kim Jee Woon, 2010, S. Korea)

Revenge is a theme that the Koreans have been excelling in with their films, and this particular film is an utmost distinct example.

Kyung Chu, a sadistic murderer, violently kills the fiancé of special agent Soo Hyun. After a while, the police discover parts from her mutilated body in a river and her father, who happens to be the chief of police, presents Soo Hyun with a list of suspects. Subsequently, he takes an absence of leave in order to discover the culprit and to exact revenge.

Kim Jee Woon portrays revenge as the utmost human driving force, the sole reason that could cause an individual to resort to extreme measures. Furthermore, he presents a battle between good and evil. However, as the revenge process is chronically extended, the borders between the two become less visible, eventually reaching the point of doubt regarding the actual “monster” between the two.

Both of the protagonists, Byung Hun Lee as Soo Hyun and Min Sik Choi as Kyung Chu, are sublime in one of the best duels in the history of cinema.

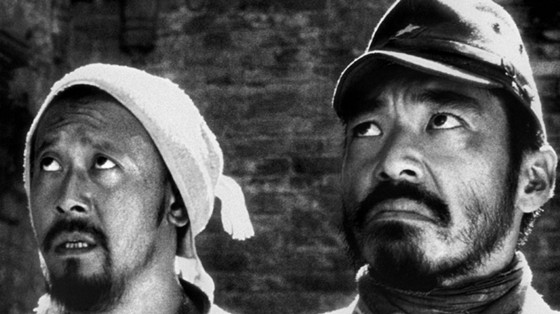

12. Devils on the Doorstep (Wen Jiang, 2000, China)

In a Chinese village during the occupation, a stranger leaves two bags outside the door of a farmer’s house with two prisoners inside them: a Japanese soldier and his Chinese interpreter. The farmer decides to keep them alive until the stranger returns, while the rest of the residents of the village set to interrogate them. During the procedure, the Japanese curses at the villagers and asks them to kill him. However, the interpreter, who is considered a traitor by his compatriots, alters his words in order to save both of their lives.

Wen Jiang directed, wrote and starred in a wonderfully ironic situation comedy that focuses on the eternal irrationality, which connects man with bloodshed. He presents his characters chiefly as tragic figures that trigger tragicomic situations by mistake, and their diversity creates quite a number of them. However, the film does not present its concept lightly, since the inevitable violence eventually enters the story with terrible consequences, clearly showing the true nature of war and violence in general.

The film is shot in black and white and the cinematography is wonderful, just as much as the acting.

11. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee, 2000, Taiwan)

Even further celebrated than “A Separation”, this particular film is the magnum opus of Ang Lee, probably the most beloved Asian filmmaker in the West.

The film takes place in 18th century China and revolves around the life of a young aristocrat, who is also an accomplished warrior-thief. Her martial arts teacher is a notorious assassin that leads her towards illegality. Two warriors, who share a platonic relationship, realize her identity and attempt to stop her.

Ang Lee managed to take a Wuxia novel mostly concerning martial arts and transform it into a delirious, audiovisual poem, where each character fights for a different reason: love, honor and recognition. However, eventually love is proven to be the strongest driving force.

Furthermore, the film was technically sublime, incorporating a number of exquisitely choreographed fight scenes by Yuen Woo Ping that occurred in trees, wires and on city walls.

All three of the protagonists, Chow Yun Fat, Michelle Yeoh and Ziyi Zhang perform exquisitely.