8. History Lessons (Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet, 1972)

Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet are other examples in which a lesser-known film maker followed the legacy of Bertolt Brecht and epic-theater. Straub and Huillet’s films are usually very dense and don’t have mass appeal.

One reason for this is that it is necessary to be aware of Brechtian theater in order to fully understand the film’s of Straub and Huillet. In the works of Straub and Huillet can be found re-interpretation and a very free sense of adaptation, as they always used the works of others as a starting point for their own work.

In History Lessons they chose one of Brecht’s last works, The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar. The film adaptation push the novel and theories to a far point, achieving levels of verfremdungseffekt which not even Brecht reached himself. In the film exists a man driving a car in the 70’s Rome wearing modern clothes. He conducts interviews with citizens who lived during the period of Julius Caesar’s rule. Other characters wear togas and are documented in a documentary style.

The plot distances itself, and every element of the film is distorted to accentuate distance. In the first interview there is a classic shot-reverse shot involving two characters. Later Straub and Huillet alter the shots such as pointing to the neck of the character or changing the scale of the shot or giving more emphasis to the trees in the background than to the faces of the characters.

This can be referenced as primary example of verfremdungseffekt. This method takes an element familiar to the audience and use it in such a way as to produce a strangeness concerning what the audience is seeing. This is just one example among a number of elements such as a discontinuity of sound design, unnatural and cynical acting, and three 10 minutes shots of a car driving the city. History Lessons remains one the finest examples of Brechtian techniques cinema.

9. O Lucky Man! (Lindsay Anderson, 1973)

After winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes with If… Lindsay Anderson was heralded as one of the most interesting figures in British Cinema. This anarchist film featured the debut of Malcolm McDowell playing Mick Travis. At the time of If…, Anderson already had three movies in mind for the Mick Travis character.

O Lucky Man! is the second feature of the trilogy, and shows Mick Travis in a new adventure, one not related to If… Travis is a coffee salesman on the road to economic and social success. The film works as an allegory concerning capitalism and success in British society.

The most entertaining and Brechtian element in the film is the wonderful score by Alan Price. Price was the original keyboard player of The Animals. After an unsuccessful solo career, he was enlisted by Anderson to score O Lucky Man!. The score wasn’t intended as a usual musical accompaniment dramatizing moments in the movie.

Price and Anderson worked towards a Brecht-Weill dynamic, discussing the political ideas behind every scene employing a song. The numbers are pop songs with lyrics which comment directly on Travis’ adventures. Price makes comments with his lyrics directly as he sings onscreen. The movie opens with The Alan Price group singing the theme song.

This not the only moment in which Price appears as he performs on screen after every Travis adventure, making comments concerning the action. Anderson follows the same logic as that governing the street singer in The Three Penny Opera. Aside from this narrative point, is important to note how songs work within the film and how Alan Price’s soundtrack remains as one the greatest under-appreciated scores of the 70’s.

10. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)

By far the most extreme and disgusting film of the list, Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom follows the efforts of 4 fascists libertines as they kidnap 18 young people in order to make them go through a series of sadistic and/or sexual rituals.

Pasolini always drew from different sources for the inspiration for his films. Mostly deriving from the works of philosophers and poets, the ideas of dialectical discussions are present in every film directed by the Italian filmmaker. In Salò there are traces of Ezra Pound’s poetry and Nietzchean quotes. The film remains one the most disgusting experiences in cinema history.

One of the strategies used by Pasolini in order to make the film disgusting centers on distancing the audience from the film. Pasolini removes violence and sadism from the usual cinematic settings for such things. Instead of criminals, low-lifes or military figures, there are 18 beautiful young people being tortured by well-dressed people. This doesn’t seem groundbreaking now, but the shock the film provokes remains intact.

When all the violence is mixed with fancy dinners and poetry the viewer feels something strange which doesn’t involve experiencing normal emotions towards the characters. The acting enforces the impossibility of normal identification. The victims betray themselves at various moments and some characters start to enjoy the torture. Pasolini notes these contradictions but, like Brecht, doesn’t give any kind of answer. The real resolution is to in the head of the audience.

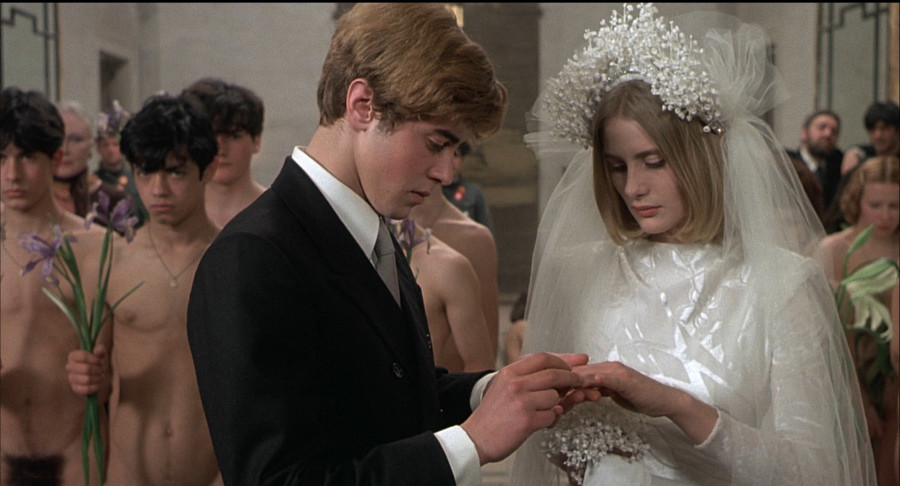

11. The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989)

Before becoming a filmmaker Peter Greenaway was a painter and a meticulous student of the history of painting. Observing his films this interest is noticeable. Greenaway conceives every frame as a painting, so the lines and colors always are among the most important elements in his films. In The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, Albert Spica (Michael Gambom) visits his new restaurant. Spica is a violent gangster who uses the restaurant to conduct his business and annoy the customers he doesn’t like.

Spica resembles Mackie Messer in many ways. Both are violent criminals who care a lot about their appearance and are always correcting the people who follow them. They both have close and secret links with the authorities in order to protect themselves. The most interesting element of the theatrical influences in the film is the appropriation of the theatrical way of staging the mise-en-scène. The camera goes from left to right pointing up the fact that it is surveying a set, a fact known to the audience.

Every film uses colors with a palette which gives priority to some colors, and excludes others. In Greenaway’s films every set has a main color, and this is taken to the extreme. The hall where the Cook (Richard Bohringer) and the Wife (Helen Mirren) share their first love encounter is red in all of its elements. The dress of the woman, the tie of man, and the walls and the lighting make everything glow in a red color uncommon to film.

12. Trust (Hal Hartley, 1990)

The English translation of verfremdungseffektit had been used mainly in two versions. “Distancing effect” is on one side, and “alienating effect” is on the other side. This list is majorly dedicated to exploring the idea of the “distancing effect” but the thought of the“alienation” idea is also useful in relation to Hal Hartley’s second feature, Trust. Trust functions in a way so as to make the audience members feel alienated, since all the characters in the film are alienated.

In Trust everybody accomplishes their social roles without question and live a mechanical lifestyle. In this environment Maria (Adrienne Shelly) tells her parents that she is pregnant. His father dies from a heart-attack after hearing the news. She becomes the object of her mother’s hatred and her boyfriend breaks up with her. In this context she meets Matthew (Martin Donovan) and starts a dysfunctional relationship with him.

In this beautifully twisted romantic comedy, Hartley tries to imbue emotions to characters who live in eternal apathy towards the world. The intimate scenes between Maria and Matthew are reminiscent of those between Mackie and his wife in The Three Penny Opera. Maria declares her love in the most emotionless way possible. The way that Hartley takes concepts of performance from the epic-theater with interesting results.

Instead of creating distance, there is immediate sympathy for Maria and Matthew and their emotionless lifestyle. In the world portrayed by Hartley, this reaction looks like the most natural thing in the world, and there is compassion for the characters. This is a curious use of the Brechtian technique that contrives to achieve quite the opposite of what Brecht intended, but the result is nevertheless interesting and effective.

13. Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997)

In Haneke’s Funny Games the action centers around the holiday of a wealthy Austrian family. The journey starts in the car, joining the family as they smile until the father puts on the radio and a heavy metal song starts. Behind the credits of the film, the family keeps on smiling, seemingly hearing another kind of song. This introductory scene can be seen as a joke commencing at the starting point of the film.

The audience is with the family and part of the family and has already identified with them in the context of the film. After less than five minutes, the viewer is violently taken out of the comfort zone by songs which the characters can’t hear. Haneke violently relates that the viewer is watching a movie, and that it is not going to be family entertainment.

Funny Games is one of the best films employing Brecht’s techniques. Of all the movies listed, the idea of distance is most vitally important in Haneke’s film. The distance for Brecht was used to provoke conscience and thinking in the audience. In Funny Games the film aims at this consideration.

The main scene which links the movie with Brecht, and one of the most famous scenes in the Austrian director’s filmography, is when the mother, Anna (Susanne Lothar), can finally shoot Paul (Arno Frisch, one of the torturers, and give the family the opportunity to escape.

When they are start to run, the other torturer, Peter (Frank Giering), takes the remote control and starts to rewind the film being watched. Haneke omits any kind of identification, first again supporting the family, giving a moment of victory, only to take it away immediately. This puts the viewer back reality, knowing that the family is not going to win. The whole film is constructed in this mode with the viewer, being forced to think about the role of a spectator.

14. Dogville (Lars Von Trier, 2003)

Again referencing The Three Penny Opera, Lars Von Trier was inspired by the show’s second most famous song, the revenge-song Pirate Jenny. Like Mack the Knife it was turn into a popular hit song with versions by Nina Simone, Marianne Faithfull and many others.

The idea of pirates killing everybody in order to avenge Jenny was enough to inspire Von Trier to create with a new idea with the same ending. Grace (Nicole Kidman) is escaping from the law for unknown reasons. She hides out in Dogville, where she is allowed to stay in exchange of working for the people of the town. As time passes she starts to discover that the townspeople don’t like her, and they start to turn their suspicions into hostility.

The setting and style of the film is one a distancing dream effect. The scenery in Dogville consists only of white outlines drawn onto a black floor. In the middle of every house is seen the name of the owner. The main street of the town is just a black floor, and some elements such as flowers are talked about and touched by the characters, but they are not there and are an invisible element.

One of the interesting aspects of the film is that it takes not only from theatrical distancing elements, but also takes advantage of some things which are possible only with a camera. The film introduces virtually every scene with a shot from above that shows the entire setting of the film. This Godly point of view reveals the artificiality of the film, making it clear from the opening that this is just a film.

The division of chapters with names which describes the action is also a direct Brechtian context. As an example, there is the name of chapter 9 “In which Dogville receives the long-awaited visit and the film ends”. The viewer knows from the beginning that there will be nine chapters, but Von Trier lets the viewer know how the film is going to end.

15. Palindromes (Todd Solondz, 2004)

Palindromes remains one of the most experimental films directed by Solondz. The film concerns Aviva, a 13-year-old girl whose her parents force her to have an abortion and who finds out that she is not able to have any children thereafter. After this Aviva goes from misfortune to another, confused by her sexual awakening.

Of all of Brecht’s main techniques, the one that hadn’t been mentioned is his use of actors and method of assigning them roles. In Brecht’s plays an actor could play more than one character without using make-up or costumes to try differentiate. In Palindromes this idea works in an opposite way and turns into an extreme distancing device. Aviva is played by 8 different actors of different ages, races and genders.

Aviva goes from a redhead adolescent girl to an adolescent boy, to a black girl to a caucasian woman. In a film full of uncomfortable moments , every change in Aviva’s appearance makes the audience uncomfortable and turns the movie into a very weird trip which not easy to follow. Palindromes is one of the most courageous modern Brechtian experiments, whether or not the experiment can be considered successful.

Author Bio: Héctor Oyarzún is a film student in the Valparaíso University of Chile.Since he was a kid his most important occupation is watching films. He also likes punk music and playing guitar.