11. A Beautiful Mind (2001)

Tragically, the subject of this film, John Forbes Nash, Jr., and his wife, Alicia, were killed in May of this year, passengers in a New Jersey taxicab whose driver lost control. Nash was 86; Alicia was 82.

The film is adapted from the “unauthorized” biography of the same name, written by Sylvia Nassar. The founder of game theory, a RAND Cold War strategist and winner of a 1994 Nobel Prize in economics the film depicts Nash’s plunge into paranoid schizophrenia beginning at age 30 and his spontaneous recovery in the early 1990s after decades of torment.

The film diverges substantially from actual events in Nash’s life (compare with the far more accurate PBS documentary A Brilliant Madness). Notably left out of the film was the fact that Nash compartmentalized his secret personal life, hiding his homosexual affairs with colleagues from a mistress, a nurse who bore him a son out of wedlock, while he also courted Alicia Larde, an MIT physics student whom he married in 1957.

Their son, John, born in 1959, became a mathematician and suffers from episodic schizophrenia. Alicia divorced Nash in 1963, but they began living together again as a couple around 1970. The son Nash had with Alicia (“Johnny”) also suffers from paranoid schizophrenia.

While director Ron Howard claimed that no literal representation of Nash’s life was intended, some have lamented that the omissions left moviegoers with a glorified impression of Nash. Indeed, also not noted in the film was the fact that Nash left his mistress nurse upon finding out she was pregnant. The image of Nash that emerges from the movie is, one concedes, romanticized: but that’s Hollywood.

What any film can do – brilliantly – is convey the nightmare of paranoid schizophrenia. In A Beautiful Mind, Howard successfully seduces the audience into Nash’s paranoid world. We may not leave the cinema with much competence in game theory (the film fails miserably in conveying scientific ideas (compare with Pi)), but we do get a glimpse into what it feels like to be mad – and not know it.

However, as in Shine and Rain Man, the image of mental disability projected by Howard is dangerously simplified: particularly the film’s assertion that full-blown schizophrenia like Nash’s can be overcome by mere strength of mind. His late-life remission, in the 1990s seems to be more in the nature of an inexplicable miracle.

Howard’s successful seduction, Akiva Goldsman’s writing and the casting of Russell Crowe, Jennifer Connelly and Ed Harris, among others, does make the film quite entertaining. The Academy thought so, as the film secured four Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress (Connelly).

12. Schindler’s List (1993)

This film is worth seeing for its sheer ambition, even with the knowledge that it was a fictionalized account “based” on a true story. In combining the directorial talents of Steven Spielberg, the pristine acting ability of titans Ralph Fiennes and Ben Kingsley (and, yes, even Liam Neeson) and add John Williams’s haunting score and Janusz Kaminski’s breathtaking black-and-white cinematography and Steven Zaillian’s majestic script, the result is most assuredly going to be nothing short of epic.

The movie is adapted from the Booker-prize winning novel (historical fiction), Schindler’s Ark (released in the U.S. as Schindler’s List), published in 1982 by Australian novelist Thomas Keneally. The movie (and the book) tells the story of Oskar Schindler, a Nazi Party member who turns into an unlikely hero by saving 1,200 Jews from concentration camps all over Poland and Germany.

The movie is very significant in the Holocaust remembrance, and is considered as one of the greatest on cinema’s history, and was screened around the entire world. As is common in Hollywood, however, creative license is ever present.

There were several key aspects of the film that were fictionalized. Oskar Schindler did not write out a list of people to save, he did not break down in tears because he thought he could have saved more people, and it is unlikely he experienced a defining moment, such as seeing a girl in a red coat, that led to his decision to save the lives of his Jewish workers.

What makes the story of Oskar Schindler so fascinating is he was not a saint. He cheated on his wife, he drank excessively and he spied for Abwehr, the counterintelligence arm of the Wehrmacht (the German military), in Czechoslovakia.

But the personalities and characteristics of human beings cannot be spliced. Sometimes character flaws, such as hubris, also lead to great achievements through a willingness to attempt something most people never would. Schindler’s espionage activities on behalf of Germany, while regrettable to enemies of Germany, later put him in a position to save many lives.

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Schindler set up an enamelware factory in Krakow that used a combination of Jewish workers interred by the Germans and free Polish workers. His initial interest, of course, was to make money. But as time went on, he grew to care about his Jewish workers, particularly those with whom he came into contact on a daily basis. In addition, helping Jews became a way to fight against what he viewed as disastrous and brutal policies emanating from Adolf Hitler and the SS.

Schindler did not create “Schindler’s List.” In 1944, with Germany threatened militarily, exterminating Jews increased in many places, but a strategy to move factories deemed vital to the war effort also emerged. Oskar Schindler convinced German authorities his factory was vital and that he needed trained workers.

But Schindler did not author or dictate the list of who would go on the transport, as was dramatically depicted in the film. Instead, Marcel Goldberg, a Jewish “clerk” assigned to the new Plaszow commandant Arnold Buscher, played the largest role in compiling the transport list.

All that being said, while there will always be those who question the motives of others, those who have examined Schindler’s efforts find him heroic. The defining measure of Schindler’s commitment to doing everything possible to save his Jewish workers came in the fall of 1944, when Schindler chose to risk everything to move his armaments factory to Brunnlitz.

Schindler could easily have closed his Krakow operations and retreated westward with the profits he had already made. Instead, he chose to risk his life and his money to save as many Jews as he could.

13. Raging Bull (1980)

Perhaps most the most interesting facet of this film is that it came about at all. Director Martin Scorsese had no interest in the film, no interest in the subject matter, nor even any knowledge of boxing. Only at the insistence of his good friend, and lead actor, Robert DeNiro, did the film even come into existence, much less morph into the classic it became.

The film depicts the life and career of Jake LaMotta, an Italian American middleweight boxer whose self-destructive and obsessive rage, sexual jealousy, and animalistic appetite destroyed his relationship with his wife and family. The film also stars Joe Pesci, who would later star in other films with DeNiro (including Goodfellas, reviewed here).

The film is adapted from Raging Bull: My Story, an autobiography La Motta had cobbled together with the help of writer Joseph Carter and boyhood friend Peter Savage. It was not much of a book, even by the primitive standards of sports bios, circa 1970. But Savage was also an acquaintance of De Niro’s and had sent him a copy, and the actor somehow perceived subtexts—maybe even a sort of rough sublimity—in it.

But it was not only Scorsese’s apathy toward sports that contributed to his initial inattention to this project. Scorsese was experiencing a professional crisis of conscience, still reeling from the critics’ severe panning of his New York, New York, a strange hybrid of a movie, partly a lavish tribute to the big-scale MGM musicals of the 1940s and 50s, partly an improvisatory love story tracking the combative relationship between a saxophone player/band leader (De Niro) and his songstress (Liza Minnelli).

After hitting bottom (including a life-threatening sickness and cocaine addiction), Scorsese decided to put his faith in his boyhood friend (the two had also previously made Mean Streets and Taxi Driver).

Aside from the fact that Raging Bull’s boxing sequences remain the most powerful ever shot, the film demands to be read, in part, as a kind of critical gloss on the boxing genre. It touches, for example, on La Motta’s relationship with the Mob—the usual central conflict in fight films—but only lightly.

It more than lightly touches on the brutality of the sport, but does not argue, even implicitly, that it should be banned or cleaned up. It has its religious implications—there are moments when La Motta can be seen as a martyr (a few drips of his blood on a ring rope), but they can easily be missed in the fury and flurry. In truth, Raging Bull remains sui generis. The long writing process and the concentration of its direction focus our attention on thoughtless, heedless behavior in a way that few movies do.

Its stripped-down behavioralism, its refusal to explain or justify anyone’s actions, remains close to unique in American movie history. If the film has any roots they are in Italian neo-realism, which, come to think of it, was all the rage—not least with the young Marty Scorsese—at the same moment the real La Motta asserted his claim on our attention.

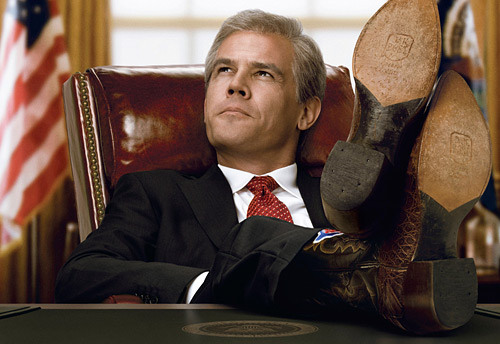

14. W. (2008)

In making this film, director Oliver Stone decided to keep closer to actual events than his more “revisionist” films JFK and Nixon. Yet the film is far from a chronological record of the former president, instead organizing episodes to observe the development of his personality, not his career. Even several spellbinding scenes about the run-up to the Iraq war are not so much critical of his decisions as about how cluelessly, and yet with such vehemence, he stuck with them through thick and thin.

Wounded by his father’s disapproval and preference for his brother Jeb, the movie argues, George W. Bush rose and rose until he was finally powerful enough to stain his family’s legacy.

The focus is always on Bush (Josh Brolin): His personality, his addiction, his insecurities, his unwavering faith in a mission from God, his yearning to prove himself, his inability to deal with those who advised him. Not surprisingly, in this film, most of the crucial decisions of his presidency were shaped and placed in his hands by the Machiavellian strategist Dick Cheney (Richard Dreyfuss) and the master politician Karl Rove (Toby Jones). Donald Rumsfeld (Scott Glenn) is well portrayed at loyally towing the party line.

But what made them tick? And what about Colin Powell (Jeffrey Wright) and Condoleezza Rice (Thandie Newton, who had barely any lines and even those were poorly done)? One will not find out in this film. The film sees Bush’s insiders from the outside. In his presence, they tend to defer, to use tact as a shield from his ego and defensiveness. But Cheney’s soft-spoken, absolutely confident opinions are generally taken as truth.

And Bush accepts Rove as the man to teach him what to say and how to say it. He needs them and does not cross them. Yet in the film it is these “insiders” who are portrayed as the real bad guys who, the film suggests, work with duplicitous motives for dishonorable ends they really don’t believe in.

The film is not without its flaws. It leaves out 9/11. This shows such glaring bias that it is hard for the film to recover from it. Imagine a filmmaker making a movie about FDR’s decision to enter World War II – and omitting December 7, 1941.

Also, the film cannot decide whether we are supposed to sneer at Ivy League privilege or Texas down-home idealism. It takes shots at both frat-boy privilege and Southern populism. But by trying to tar Bush with these two different brushes, the filmmakers only succeed in making him seem like he was enriched by and transcended both.

One might feel sorry for George W. at the end of this film, were it not for his legacy of a fraudulent war and a collapsed economy. The film portrays him as incompetent to be president, and shaped by the puppet masters Cheney and Rove to their own ends. If there is a saving grace, it may be that Bush will never fully realize how badly he did.

Author Bio: Paul Vicary lives in Miami, Florida, where he works as an attorney. In addition to practicing law, he is a freelance book reviewer and runs a non-fiction publishing house.