11. Altered States (1980)

Empire Strikes Back may have grabbed all of the attention, but Ken Russel’s Altered States wanted to solve the inscrutable nature of the the meaning of life — while tripping on mushroom inside isolation tanks, waxing rhapsodic about communion with God, and physical reconstitution back to original man.

It was quite a head trip in more ways than one — its chaotic, hyperactive, sublimal editing, paired with John Corigliano’s titantic score, as directed by one of cinema’s greatest outlier visionaries who never fit within the establishment in any way shape or form, actors who delivered screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky’s brilliant dialog and breakneck pace, and Jordan Cronenweth’s lumionous cinematography, made for an evening one would never forget. No one had ever seen anything like it.

Altered States verbalizes what 2001 left unsaid. Altered States visualizes the symbiotic relationship between our ancestor apes and ourselves, and that this link, this memory, is embedded in our DNA and can be extracted and reconstituted. And in this reconstitution is the answer to the meaning of life. A scene in a restaurant:

Dr. Eddie Jessup: What’s whacko about it? I’m a man in search of his true Self. How archetypically American can you get? Everybody’s looking for their true selves. We’re all trying to fulfill ourselves, understand ourselves, get in touch with ourselves, face the reality of ourselves, explore ourselves, expand ourselves. Ever since we dispensed with God…we’ve got nothing but ourselves to explain this meaningless horror of life.

Dr. Mason Parrish: You’re whacko.

Dr. Eddie Jessup: Well, I think that the true Self, that original Self, that first Self, is a real, mensurate, quantifiable thing — tangible and incarnate… and I’m going to find the fucker.

Ken Russel’s ape kills. Kubrick’s ape kills. Kubrick finds God in the outer recessess of the infinite. Russel finds God in the inner recesses of our cerebral cortex. Both films deal specifically with a real, quantifiable physical change to make manifest the ultimate discovery. A sacrifice is required and redemption seals the deal.

I encourage everyone to see this film.

12. Blade Runner (1982)

3 years after Alien, Ridely Scott does it again!

Alien did not so much reinvent a genre as mix-and-match several to brilliant effect. That and billiant photography cemented its status.Blade Runner, on the other hand,was something completely new and original. Blade Runner became the “modern” 2001, influencing countless of dystopian sci-fi films afterwards. Blade Runner was rumored to be the most difficult film production ever (until James Cameron’s Abyss.)

As original as Blade Runner is, there are still a number of clear references to 2001 and many other Kubrick films as well. Joe Turkel, a Kubrick regular, is the computer genius in the film that builds the replicants. Last seen, he was servicing Jack Torrance drinks. An ongoing game of chess in Tyrell’s apartment awaits the next move.

The opening shot — a slow forward tracking shot towards a mega-building is intercut with an extreme closeup of an eyeball. In fact, eye symbolism runs rampant through Blade Runner as it does in A Clockwork Orange. We have manniquins in Blade Runner that look like the manniquins in Killer’s Kiss. Pan-Am logos proliferate in boths films. Both feature video phones. Unused helicopter footage from The Shining was used in the ending of Blade Runner. The scene of Tyrell’s apartment bathed in candlelight looks like similar shots in Barry Lyndon.

The city of Los Angeles never looked dirtier, never looked wetter. The production design influenced sci-fi film for decades. Its extreme violence put off many, as did the rambling, meandering plot, and loosey-goosey script. Little was affirmed. Even the “happy ending seemed false. Nothing was explained. One needed to pay close attention to the film’s semiotics to glean any kind of meaning.

13. The Abyss (1989)

I want to take this time to talk about one of my guilty pleasures — Millenium. There’s probably nothing in this film that anything to do with 2001 or Kubrick but it is a superb sci-fi film that understands time travel, built on the foundations of a good story compellingly directed, and features two leads that are remarkably beautiful to look at and have great chemistry — and that’s hard to say about Kris Kristofferson.

His wooden delivery doesn’t always work, but in Millenium his usual quirks are all but gone or, if not gone, made part of his character in an organic way. The plot is ingenious and Cheryl Ladd is resplendent as an alien-from-another-world time-traveler. It truly is one the most under-appreciated sci-fi films of the 80s.

Now, The Abyss.

James Cameron has admitted his affinity to Kubrick and 2001 in numerous interviews. The Abyss is his answer to it. Prior to this film, Blade Runner had the reputation for the most difficult shoot. Afterwards, The Abyss easily surpassed it with almost reckless abandon.

Filmed largely underwater in an abandoned reactor tank in South Carolina, the film pushed the envelope for crew and talent safety with grueling 20-hour days. And oh, did I mention it was largely filmed underwater — no smoke-tank-for-water simulation here. Cameron strove for maximum practical effects whenever possible.

The plot is pure sci-fi — an entire civilization of beneficent aliens live deep underwater and decide to teach humanity a lesson before it destroys itself. Combined with this end-of-the-world scenario, Mr. and Mrs. Brigman fight, make up, fall in love again, and then are separated —twice! — by the cruelest of sacrifices only to be reunited in the end under the most extraordinary circumstances possible. And then there are the Navy Seals and an approaching Cat 4 hurricane. Just go with me here.

Cameron achieves the impossible with maximum commitment from his cast and crew. He knows how to direct his actors and actions sequences for the largest payoff. Like the crew and vessel from Alien, the roughnecks and underwater rig from The Abyss are well lived in and familial.

The physical effects are jaw-droppingly realistic. After a particular catastrophic series of accidents, the crew is cut off from humanity and its life-support systems barely holding on. Brigman has to make the ultimate sacrifice to save his crew. Cameron devises his own “Stargate” sequence to save Brigman and humanity at the same time.

Clearly, there is nothing Nietzschean about this. Cameron is on a feel-good wavelength and wants to teach humanity a different lesson. But that does not diminish the passion Cameron feels for 2001 and his quest for the ultimate trip.

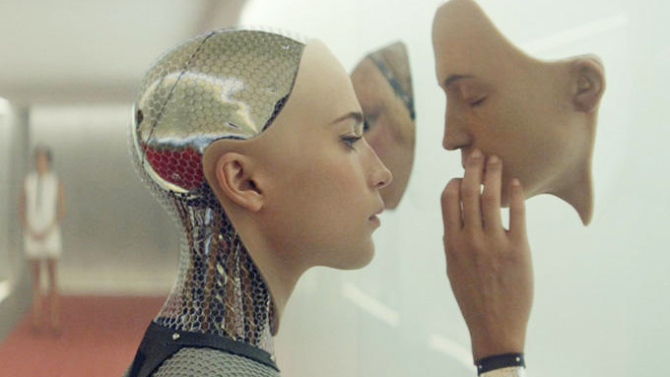

14. Ex Machina (2015)

Quite simply, this is one of the best films of the 2015.

Ex Machina takes its title from the Latin phrase Deus Ex Machina — literally, god of the machine. In a literary or theatrical context, it means a force often heretofore unseen materializes and brings the play to a sudden close by manufacturing an ending that may or may not have grown organically from the story.

One could very correctly state that the Stargate sequence in 2001 was one such manufactured ending although many feel differently. The Abyss, too, seemed to come out of nowhere, however spectacular the ending sequence. Ex Machina ends in a way that brings multiple interpretations but mainly your jaw has dropped and WTF wants to come out of your mouth but you’re so stunned you can’t speak the words.

Ex Machina takes the concept of artificial, heuristic intelligence and finds a completely new way to express evil in technology and how, despite our best efforts, technology will always find a way bite back. This movie expands on HAL and expands on all the other android-like concepts that 2001 made possible and puts a computer program in a sexy woman’s android body.

The conversations so clearly mimic the types of conversations in 2001 it’s uncanny. But not mimic in a plagiarist sense, but with due homage, reverence, and smarts. Ava, acted with unbelievable clarity and precision by newcomer Alicia Vikander,not only wants to break free, she wants to eat your guts while doing it, metaphorically speaking.

HAL programs a pod to run into Poole. He allows Bowman to leave the ship but refuses entry later. Ava messes with your mind in the same way. Whereas HAL could read lips, Ave senses lack of purpose or clarity and plays on ones innate lack of self-esteem. She’s a trickster and she’s out for blood.

Jurassic Park has one of the best exchanges about the ability of organisms to adapt. And let’s face it, all film androids, regardless their artificial makeup, are treated like living organisms.

Dr. Ian Malcolm: John, the kind of control you’re attempting simply is… it’s not possible. If there is one thing the history of evolution has taught us it’s that life will not be contained. Life breaks free, it expands to new territories and crashes through barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, uh… well, there it is.

John Hammond: [sardonically] There it is.

Henry Wu: You’re implying that a group composed entirely of female animals will… breed?

Dr. Ian Malcolm: No. I’m, I’m simply saying that life, uh… finds a way.

Ex Machina is how life — even animatronic life — finds a way. Brilliant film and will leave you breathless and scared.

Honorable Mention: Fidelio (1805), an Opera by Ludwig van Beethoven

Kubrick 2001 references are not saddled to exclusively to film.

A recent 2015 production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio (1805), at the Salzburg Festival, is rife with 2001 symbolism, sound effects, and heavy breathing.

There is a large, looming monolith (pictured). When the monolith rotates, a similar, foreboding hum heard (as when the elevator door opens upon arrival at the space station). There are additional clunky noises.Heavy breathing as well. As the opera proceeds, The Matrix combines with 2001, and the evil jailors wear black, silken trench coats and Neo-like sunglasses. The room is a large parlor, stripped of all its furniture — like what the room at the end of 2001 would look like sans furniture and stretched tall.

Historically, Fidelio is a particularly difficult opera to stage. After its premiere in 1805, Beethoven spent the next 10 years revamping it and wrote 4 different overtures. The opera has huge story issues compounded by the fact it exists smack dab in the middle of transition from the old to new. It is written in the style of Singspiel— this means there is a lot of spoken dialog that alternates with musical set-pieces.

Its episodic format often does not fit the transcendent and magnificent music written for it. Like filmmaking, all the elements have to cohere meaningfully and in the hands of a poor stage director it can make for a mixed bag and a long evening. Even good opera stage directors have struggled— the director here is hardly the first.

And musical conductors have almost always tried to emphasize the importance of the music over the drama in an effort to make the Singspiel unnecessary, even redundant. Artistically, it’s a mash of competing desires. It is still a masterpiece because it’s still Beethoven, but slightly diminished in status.

This director, Claus Guth, is famous for reimagining (to put it kindly) and combining beloved, almost sacred operatic productions with popular films, creating modern mashups that are controversial to say the least. His version of Wagner’ Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) or the Ring Cycle for short — four separate operas make up a mythic version of the history of the world with gods, goddesses, giants, humans, and those in-between — is reworked into the cinemascape of The Truman Show.

Wotan, a one-eyed leader of all the gods, is now a movie director manipulating models of the operas sets and singers. Hand-puppetry was used to brilliant effect in Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s concept for his own film of Wagner’s opera Parsifal (1982). In either case, I can assure you, this was not Richard Wagner’s original intent. Nor is it Beethoven’s.

Claus Guth goes all in with his concept and dispenses with the Singspiel altogether. The monolith rotates to bridge scene with dialog. The first act salon is represented as a stark, all white set except for the black monolith. The singers wear monochromatic clothing. Their shadows are projected on the bare white walls, and become a kind of statement of duality (technically, this had to be very difficult).

Everything about this isn’t Beethoven in the least, except somehow it is because the music transports you into ever dizzying heights. I have to admit, I liked this production a lot. It’s very similar to Willie Decker’s La Traviata — which reimagines the story in Dali-esque, surreal ways. Opera aficionados with a desire for traditionalism will mostly hate it. If you are younger grew up with the movies, you’d love it.

Conclusion

In opera they have a word for the type of show described above — Regie theater — or director’s theater. Kubrick himself had been accused of Regie theater more than once in his imposing career, although in film it’s generally called self-indulgence.

Regie theater specifically describes operatic productions whereby the director has diverged considerably from traditional staging or composer’s intent, often changing or eliminating geographical location, chronology, plot, characters, dialog and so on.

Often, this is done to serve the ego of the director or express some kind of political statement or wild concept.Sometimes Regie theater can work quite brilliantly and succeed in bringing new life and new ways of looking at things heretofore hidden in plain sight for years. Other times (usually) not so much. 2001 went through all of that.

Insofar as Kubrick is concerned — a “Regie” director if there ever was one — one can make a case that what was originally thought self-indulgent is really just a very smart director playing smartly with all the elements of genre and maximum technique to create new ways of telling story. From Dr. Strangelove to 2001 and beyond, he achieved perfect symbiosis and crafted films of such uniqueness and perspicacity that even to this day his streak remains unmatched by anyone else.

It is interesting to notethat the word ‘fidelio’ was the password to gain entrance into the orgy in the film Eyes Wide Shut. And the plot of Fidelio — originally titled Leonore, oder Der Triumph der ehelichen Liebe, or The Triumph of Married Love — is all about fidelity to one’s husband and the triumph of good over evil.

Fidelio ends triumphantly — love conquers all — at least in some productions. In others, the hero, overcome with emotion at being freed, falls dead on the final crescendo. There is precedence for both ways.Eyes Wide Shut ends elliptically —where love is a compromise, not a triumphal march and little is affirmed, won, or denied. Dr. Harford may as well be dead for all the good he did.

Many endings in Kubrick’s career have ended ironically, not decisively or happily. 2001 trumps all others, of course, are there are healthy discussions over its intended meaning. The films 2001 inspired generally close with similarly strong sentiments too — maybe not all the questions were answered, as in Blade Runner, or Kubrick was always a director’s director.

From difficult, uneasy beginnings he crafted a career that was long-lasting and maximum impact. The world’s great directors waited with baited breath for what would come from his vibrant, imaginative, challenging imagination. No matter what it was, everyone knew it would knock their socks off.

Author Bio: Mark Krasselt is a writer, designer, and all-around creative who reads too much and has seen too many movies. He has been fascinated with Stanley Kubrick since his first saw 2001: a space odyssey at age 8, and this fascination has never abated. He has even written a long thesis on the famous director, titled “Stanley Kubrick: lessons of a Sentient,” which he hopes to expand into an even longer book.