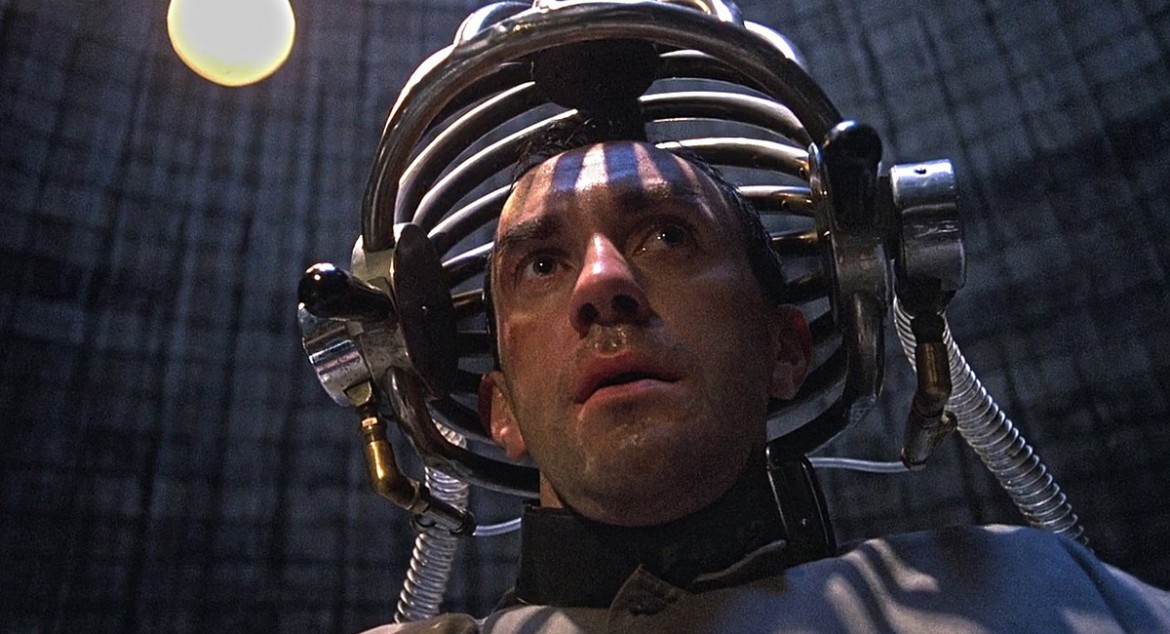

5. Brazil (Terry Gilliam, 1985)

Science fiction has always been one of the genres most used to describe society. But, if “Videodrome” was set in a world near to us that nowadays is in the past, Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil” makes up an entire alternative society, in which Gilliam’s twisted and brilliant mind can be left unchained. More precisely, “Brazil”, like Murnau’s “Nosferatu” with Dracula, is unofficially based on George Orwell’s “1984”, but is more faithful to the literary original than its official cinematography transposition.

Everything begins with an error. An insect falls into a typewriter, in a dystopian society “somewhere in the 20th century”, causing an arrest and the entire hallucinated, dark, surprisingly funny plot of the movie.

The protagonist Jonathan Pryce is submissive, buried by all the useless bureaucracy (just like in “The Trial”), with which this original Big Brother controls the entire civilized world, but just cannot prevent the randomness and the irrationality of it and he is, therefore, compelled to annihilate and suppress the (literal) bugs in the system.

Terry Gilliam is completely free of restrictions and this can be easily seen on screen. He uses astonishing dreamlike sequences, oppressive atmospheres (blatant also in the architecture of the “dark city”, derived from movies like “Blade Runner” and seminal for future 90s sci-fi masterpieces) and an authentic hatred for every kind of government or schedule that explodes in the last visionary, liberating and, unfortunately, fake 20 minutes, where every representation of bureaucracy or authority is destroyed and blown up. But this catharsis can’t be real, and the society takes the bug back and absorbs it, after having regurgitated it.

4. The Tenant (Roman Polanski, 1976)

“The Tenant”, by the brilliant and diverted mind of Roman Polanski, is probably the most frightening and psychologically disturbing movie on this list. With a similar subtext to “Shadows and Fog”, it is a slow descent toward mysterious conspiracies and private madness, pagan religions and strange neighbors.

Trelkovsky (interpreted by Roman Polanski himself in a short circuit of reality and fiction that can also be found in the movie), who has just started to live in an apartment in Paris where the last tenant committed suicide, is the typical Kafka-like character. He is a victim of the events, puzzled but not shocked by the episodes he lives or sees from his rear window, innocent but blamed for every little thing he does (or does not), implicated in something beyond every attempt of understanding.

Polanski directs the movie, as usual, perfectly, with a great sense of terror and anxiety, culminating in the last 15 minutes of pure inventions that make all the tension explode and render it intolerable. “The Tenant” is Polanski’s best genre film, maybe better than “Rosemary’s Baby”, because of one simple reason: Trelkovsky’s story is not so distant from all of us, what happens to him could really happen to anyone.

Polanski is a genius in never explaining anything; every supposition the viewer makes is possible, but not certain, and the ending, instead of clarifying the many mysteries scattered through the film, amplifies and increases them, in a Moebius-like structure that is never going to end.

3. L’udienza (Marco Ferreri, 1972)

A man named Amedeo wants to speak to the Pope. He wants to talk with him face to face, because he must tell him something very important, something that moves to tears the most famous theologian in the world. Something unknown.

“By looking at the middle-class aspect of Amedeo, he probably will tell the Pope something of little significance or what the mass, of which he is a perfect representative, would say to the pontifex if it could approach him,” says Alberto Moravia about the movie, highlighting the nonsense not just of the indistinguishable line that separates the clergy from the procedure and bureaucracy of political power, but also of the mass and its masochism and its auto-destructive force.

Amedeo is played by the Italian singer Enzo Jannacci, who keeps just one expression throughout the movie, and surprisingly it is a positive thing. He is astonished by what is happening to him, but somehow aware of living in a movie (he says more than once “What a Kafkaesque situation!”), but, like every character in the film (and like in Kafka’s books, particularly “The Castle” from which “L’udienza” is inspired), it’s impossible for us to empathize with him.

On the contrary, we are almost scared by him, because we know that Amedeo is us. We can see what is happening, knowing that we (and Amedeo) are going to be defeated, until another innocent and probably ignorant citizen will want to speak to the Pope.

2. The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

Until now we have talked about movies inspired or just similar to the crux of Kafka’s poetics. That is because basing a movie on a novel by Kafka is incredibly difficult for its inherent characteristics and writing, which are nearly impossible to express on screen. Only a genius like Orson Welles could manage to make a film based on Franz Kafka’s “The Trial” and make a triumph out of it.

The story is practically the same as in the book, just set in the then-contemporary 1950s, during the economic boom. This intuition gives Welles the opportunity of freeing his baroque style (equaled only by Mr. Arkadin) and his virtuosity (the first long take is something so oppressing and claustrophobic, thanks also to the repeated use of a wide angle lens, that it is difficult to describe), without losing control on the meaning of the novel, but accentuating it (the animated opening that references to the art of cinema, the huge office that reminds us the one in Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment”).

This movie was criticized by many critics of that time, but Welles himself repeated that this was his best movie, no matter what everybody was saying. We shall trust him, shouldn’t we?

1. After Hours (Martin Scorsese, 1985)

Did you ever live a strange evening, when nothing seems to go well and you tried to make it work, but every attempt you make is simply useless? Even your worst evening ever, the one you remember also after a few years cannot be worse than the one filmed by Martin Scorsese, in one of his most beautiful and forgotten movies. “After Hours” marks a comeback in Scorsese’s career, which after “The King Of Comedy” had somewhat stopped, in maybe the most joyful, entertaining and funny nightmare in cinema history.

Scorsese turns off every cheerful New York light and turns on the ones in the crumbling and almost Gothic alleys of SoHo, in a dream-like run against everything. Spectacularly funny Griffin Dunne is tossed all over the neighborhood, compelled to meet all kinds of crazy people and ending up being haunted by almost every person he meets.

He is powerless and innocent throughout the movie, just like when he is literally imprisoned in the plasterboard, and the (fake) happy and funny ending is casual just as the rest of the movie, as Dunne loses $20 out of the window of a cab that is bringing him home, as being accused of stealing, as Rosanna Arquette committing suicide, as life.

Scorsese updates Kafka to our postmodern times, to neon lights, to modern life, without losing its spirit and rendering it funny. The only way to survive life is to smile at it, no matter what is happening to you. At the end, you are going to be on time at work, returned to the society. Happy ending?

Author Bio: Pietro Mauri lives and studies in Milan, Italy. He collaborates with some Italian movie websites. He writes about cinema because he says, paraphrasing Ingmar Bergman “Cinema is a need, like eating, drinking or sleeping, and every cell in my body is completely imbued with it”.