For those who don’t know, Franz Kafka is one of the major authors of the 20th century. His novels and short stories are filled with anxiety, surrealism and persecution. He uses these feelings so the reader can be shocked by the cruelty of the world and of society, but, most of all, by man, who built the two, and who is shown as what he really is: an insect.

The strangest thing in his literature is that, in spite of the absurd situations the characters are forced to live, they do not perturb them and they deal with them as if they were commonplace. The entire world collapses and every little thing, political (especially bureaucracy) or private is transformed, exaggerated and distorted by Kafka’s magnifying glass, through which he observes us all as if we were an ants’ nest, concentrating on one particular ant, observing it, until sun rays burn it down.

In this list there are some movies just inspired by Kafka’s poetics (in the atmosphere, in the construction, in the situations) or based on his works (sometimes a novel, sometimes just a phrase). So, let’s start.

10. Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2008)

At first sight, “Inland Empire” doesn’t have as many Kafkaesque characteristics, and the majority would have put in its place David Lynch’s first movie, “Eraserhead”, literally closer to Kafka than this one. But “Inland Empire” is a unique movie and is Kafkaesque in a very strange and unsettling meaning of the word.

It is probably Lynch’s least comprehensible, linear, and coherent movie (if you know his cinema, you will also know that he usually doesn’t make it easy to watch his movies), and it certainly is pure cinema that becomes art throughout its three hours of anthropomorphic rabbits, mental trips, Hollywood and gates leading to the void of human consciousness.

Surreal and surrealistic beyond any imagination, “Inland Empire” brings the viewer into a never-ending nightmare, without any start (the first scene starring Grace Zabriskie as the old neighbor is thrilling and absurd) or end. Lost in these dreams of dreams, the spectator starts to actually live a Kafkaesque situation.

You do not know what is really happening, but you can’t ask anything about it, because you want to discover where this nightmare is going to throw you. You are at the mercy of the director, inside his head, inside an absurd world. You become a character of the movie, and you can’t do anything about it.

9. Eyes Wide Shut (Stanley Kubrick, 1999)

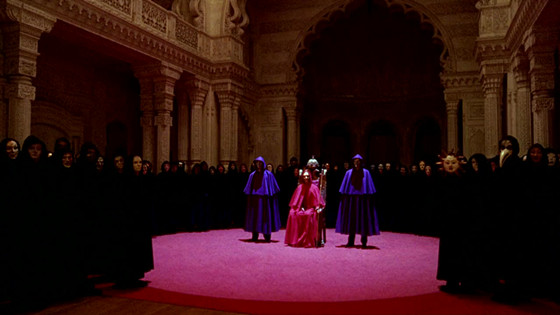

Kubrick’s elegance in camera movements and storytelling can render even the worst acts of “ultraviolence” or the grittiest and grimmest situations refined. “Eyes Wide Shut”, his last and both over- and underrated movie, expresses this perfectly. It starts as a sophisticated and theatrical war between the sexes and as a farce of marriage, but it reveals itself as a disquieting voyage through the worst obsessions of the human being and his (masculine) perversions. All in little more than one night.

It seems a serious and distorted version of Martin Scorsese’s “After Hours” (the cause that activates the plot of both movies is essentially the same). Tom Cruise’s character has no scruples, but he enters where he shouldn’t and this causes so many events that could destroy his life. He meets the most extravagant, disturbing and disturbed persons, in even more shocking sequences.

One can easily see Kafka’s influence and inspiration not just in Arthur Schnitzler’s “Traumnovelle”, on which “Eyes Wide Shut” is based, but also in Kubrick’s screenplay and choice of direction. The ending is explicative, too; every little thing that seemed to bring destruction and death disappears, and everything is reduced to one single and significant word: “Fuck.”

8. Shadows and Fog (Woody Allen, 1991)

Don’t be deceived by the name of the director. Woody Allen, probably the greatest screenwriter and comedian alive, has not just made comedies or funny movies. He has also made depressing and reflective dramas, of which the most famous are “Match Point” and “Crimes and Misdemeanors”, reflecting on life, death, existence and the presence of evil in the world. One of his best and unknown movies is the perfect mediation between his comical and his tragic aspect.

“Shadows and Fog” narrates the tragicomic story of Kleinman, a Jewish man interpreted by Allen himself, who is unjustly accused of killing a doctor (Donald Pleasence) by the inhabitants of a Central European town during the 20s and is obliged to run all night, trying to escape from both the angry crowd and the mysterious serial killer he was mistaken for. Simultaneously, a girl (Mia Farrow) runs away from a circus and from her clown lover and her destiny meets Kleinman’s.

With astonishing black and white cinematography (by Carlo di Palma) and perfect direction (Allen’s best), the Kafkaesque spirit can be felt throughout the whole movie.

The normal person that is reluctantly forced to run from everyone, involved in things that are too much for him, the strange situations (the Fellini-like circus), the soundtrack from The Three-penny Opera (references to Bertold Brecht are present in the entire movie) and an ambiguous ending, deliberately incomplete and surrealistic, contribute to a mocking, funny and tragic atmosphere.

Plus, the title “Shadows and Fog”, inspired by “Night and Fog”, a short movie by Alain Resnais about concentration camps, highlights the subtext of the movie. In fact, it is easy to see a comparison between Kleinman and his motiveless persecutions and Jewish history.

7. Franz Kafka’s It’s a Wonderful Life (Peter Capaldi, 1995)

This extraordinary and original short movie is unknown to most people, although it won an Oscar for best short film and is directed by Peter Capaldi, who was the 12th Doctor Who. It is an imaginary story about Franz Kafka himself who, on Christmas Eve, is trying to start his new tale, but he just can’t conclude the first phrase: “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself in his bed turned into a gigantic insect“.

This is the question that oppresses Kafka, interpreted by a great Richard E. Grant. Into a gigantic what will Gregor Samsa be transformed? While he cannot initiate what will become his most famous and iconic tale, “The Metamorphosis”, strange faces come to his door and a very odd Christmas party occurs downstairs.

This is probably the funniest movie in this list; it shows a reverent love for Kafka’s poetics and works, as well as making fun of these. Closer to Gothic than to surrealism, the short is a non-stop tunnel, full of direction and narrative inventions, that arrives at an unexpected Christmassy ending (complete with choirs) and a last sequence worthy of Monty Python’s most inspired moments. “Franz Kafka’s It’s A Wonderful Life” is an unusual object that deserves to be praised and watched all over again.

6. Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1984)

Writing about a movie like “Videodrome” is not easy at all. It’s a movie that has predicted (and continues to predict) so many things that it has become a legend, an artwork, a bible, and a “cathodic church”. Just telling what this movie is about seems obsolete. It is, without any doubt, a masterpiece, one of Cronenberg’s greatest works, the acme of the body horror genre and a chilling prediction of our near future that has quickly become our past and now our present.

If Cronenberg’s predictions were not right, you would not read this article on the Internet, you would not live in this global multiform intelligence, we would not have nicknames (or TV names), and our hands would not be constantly attached to smartphones as if they were guns melted to our bodies. This last fact is important to the list: one of the recurring themes of the movie, and of all the body horror genre, is the transformation of the body, most of the time caused by that of the brain.

In “Videodrome”, this concept is pushed to the extreme, not just visually, but also conceptually. James Woods’ character’s growing fear of the health of his own body and his progressive estrangement from it reflect his social alienation. In fact, the movie first shows him as “another brick in the wall”, a faithful servant of voyeurism and of (what is supposed to be) normality, but, by the end, he becomes a “crazy” and out-of-place person that must be eliminated.