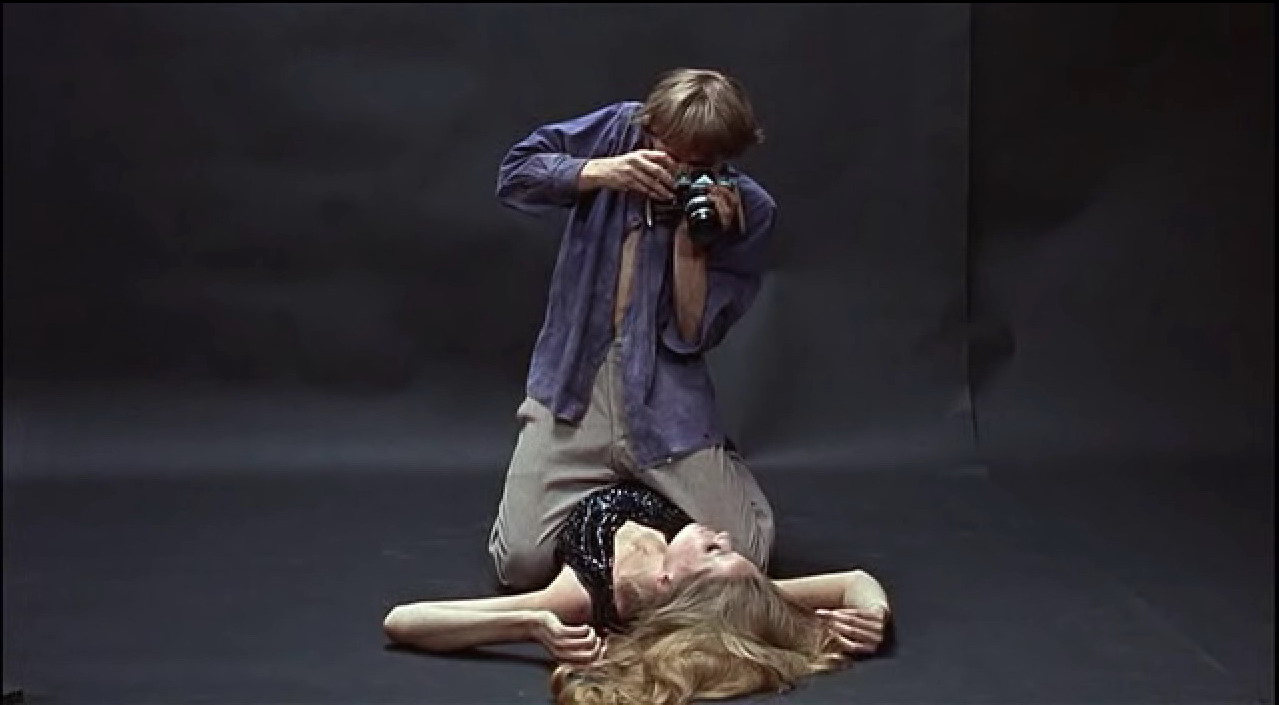

18. Blow-Up (Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

Michelangelo Antonioni is one of cinema’s most challenging filmmakers, due to his extreme nihilistic viewpoint, obsession with distance, lack of communication amongst characters, and the depression and internal torture they suffer from. His films are a reflection of this state of mind and at times are painful to watch as a result which has caused polarizing reactions.

Some contemporaries, such as Ingmar Bergman and Francois Truffaut have criticized his films as being unbearably boring, while Kurosawa Akira and Andrei Tarkovsky praised him as a master of his craft. Antonioni is usually not for everyone, to say the least. Blow-Up however is more audience friendly, while still encompassing the themes and ideas of the other films in his oeuvre.

Blow-Up sets itself up as a hip, sixties era British mystery, that starts out with a filmmaking style similar to A Hard Day’s Night. It tells the story of a fashion photographer who accidentally takes a picture of a murder and is drawn into finding out who murdered who and why. But this is merely a red herring to what’s really at hand, a character portrait of an individual whose life may or may not be purposeless and might have a mechanical personality.

It is his journey of becoming self-aware that is really the point of this movie. The film’s ending punctuates this by being inconclusive to the murder mystery, while having completed the character arc. It’s this exterior façade that makes Blow-Up easier to digest and audience friendly. It can be assumed that an audience member can watch it from beginning to end still believing it is a mystery film that happens to have an ambiguous ending.

As the film progresses, it becomes more and more like the rest of Antonioni’s oeuvre, featuring his signature shots of placing character distant from one another and the themes of extreme isolation and what it means to simply be become more present, while never having attention being diverted to them.

It’s intelligent filmmaking that never seems to be condescending or pretentious. Michelangelo Antonioni was one of cinema’s most challenging and very best masters, whose work stands as a towering enigma. While Blow-Up is not his best film (that would be La Notte), it is the one that is his most audience viable film and is still a masterpiece in every sense of the word.

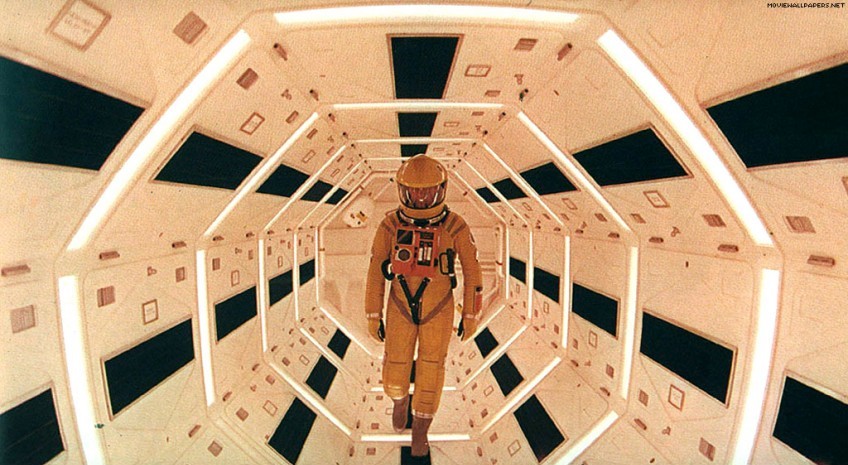

19. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

2001: A Space Odyssey is a grand spectacle of a movie that is notorious for being elusive in its overall meaning. There are four segments to the film, which are connected by omniscient presence of a monolith. The first story takes place at the dawn of man and observes a family of early hominids.

During the course of this segment, they discover a bone and learn how to use it both as a tool and as a weapon. In the second, a scientist is sent to investigate a problem in a space base that may be the result of contact from another life. This is where the film transitions into the third and fourth segments, the only two connected by a central character.

An astronaut is sent on a mission on Jupiter to further investigate the issues faced in the second segment. During the odyssey to Jupiter, the computer that had been running the ship goes haywire and becomes murderous, killing the other humans on board. Eventually, the astronaut is transported through a wormhole and the film becomes full on abstract.

2001: A Space Odyssey features existential questions of what it means to be human and the primitive nature of violence. But unlike in Blow-Up, Kubrick places these themes directly in the forefront through his stylistic decisions.

The film is very minimalistic in story, with many scenes of space ships landing and glory shots of space crafts slowly moving taking up a good portion of the films two and a half hour duration. This may baffle some viewers, but for the more attentive and patient viewers, it mesmerizes.

There is a scope to these moments that is impossible to ignore, in part due to the visual effects by Douglas Trumbull. But the credit should be given primarily to Stanley Kubrick, who orchestrates the film in such a grand fashion. The ending, which is the most ambiguous in film history, is worthy of debate and continues to puzzle and throw off viewers.

One wonders just how Kubrick and co-writer, Arthur C. Clarke, convinced studios to go along and get away with 2001: A Space Odyssey, as it is essentially a big budget art film. But whatever they did worked and audiences will forever be grateful, as it is unparalleled in both story and scope.

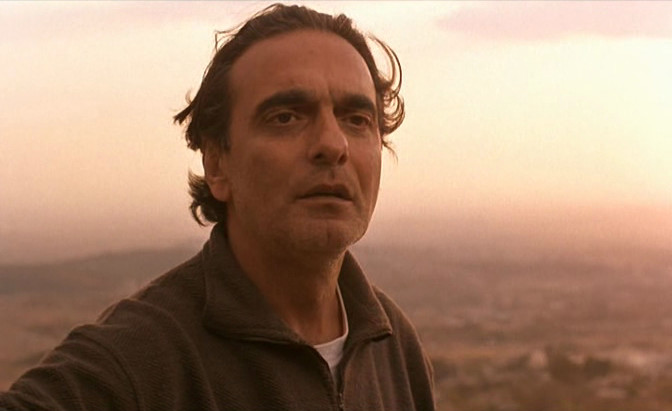

20. The Godfather and The Godfather Part II (Dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1972, 1974)

Francis Ford Coppola directed four films in the 1970s. All of which were groundbreaking masterpieces that are each commonly cited as being amongst the very best films of all time. The first of these was the incredibly popular, The Godfather, which was followed up by an equal, if not better, The Godfather Part II, which is not so much a sequel, so much as the second half- one film divided in two.

The story follows Michael Corleone, a WWII veteran whose father, Vito, is the head of one of the biggest crime families in the country. Although initially skeptical about working for his father, Michael soon finds himself as the heir to the empire he once rejected. Slowly and reluctantly, Michael begins to fall further from his roots and becomes worse than his father. Watching The Godfather movies is like watching a modern day Greek tragedy, due to their heavy themes of family relationships.

Francis Ford Coppola’s classical style direction compliments this story and emphasizes the fall from grace that Michael soon finds himself in. He and his cinematographer, Gordon Willis, use dark lighting to create a dark, uncomfortable, and sinister feel and causes the film to be drenched in atmosphere.

Coppola’s framing further pushes his ideas, with the position of the character within the space of the frame summarizing where they stand as an individual and in the situation at the particular moment. It’s unnoticeable at times, as everything feels organic and natural, as if this is the sole way this story could be told.

A film with the reputation and scale as the first two The Godfather films are simply impossible to ignore. It’s one of the few cases where it’s damning if you do not like them. They are simply great movies.

21. A Woman Under the Influence (Dir. John Cassavettes, 1974)

John Cassavettes is the father of the independent film. He would act in larger productions, such as The Dirty Dozen and Rosemary’s Baby, to get money to independently finance his less commercial films. As films go, each of them are defined by their harsh, neorealist depictions of relationships amongst families and individuals and are obsessed with the human condition.

Cassavettes would shoot his films primarily in a controlled handheld fashion on cheaper film stock, so as to give the film a documentary like aesthetic. For this reason, Cassavettes can be seen as direct descendant of the Italian Neorealist Movement. There is no better example of this than in his 1974, A Woman Under the Influence.

A Woman Under the Influence is about a hard working construction worker who loves his wife and children deeply. He begins to notice his wife has some unusual behavior and begins to suspect she may no longer be mentally stable. Eventually, he begins to think that her behaviors have become a danger to those, including and especially their children.

As such, he decides to commit her. When she returns from the ward, although she is upset by what her husband did, decides to stay with him. But despite this, the film ends inconclusively as to where the future of their relationship lies.

The above synopsis does not spoil film, as the film is not about story or plot, instead focusing on raw human emotions. John Cassavettes does this through, in part, through his casting. Peter Falk, who was a close friend of Cassavettes, and Gena Rowlands, Cassavettes’ wife, play the two central parts.

Because of their real life relationships, everyone involved feels comfortable and relaxed around one another, resulting in very naturalistic acting. This also allows room for Cassavettes to move in on his actors and literally get up close and personal with his camera.

It moves around the room, circling the action, going back and forth and intentionally missing mark at times, so as to give a gritty feel. Cassavettes uses the close-up to show the vulnerability and the fear that lives in each of his characters, thus giving a sense of intimacy not normally seen.

A Woman Under the Influence represents one of the most intimate movies ever made. It is a great example in emphasizing character and emotion over plot and story. It may be rigged for some viewers, but the experience watching it is impossible to forget.

22. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Dir. Chantal Akerman, 1975)

Up until this point, the films discussed have been about extraordinary moments or individuals. The mundane has not been discussed as of yet, even as backdrop. But with Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, it is not only now present, but is in the forefront and the subject of the movie.

The mundaneness of Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles begins in its title, which is the central character’s name and her address. This sets up exactly what the film is about, a widowed housewife named Jeanne Dielman, who lives at 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, and the daily routines and chores she does.

These routines include cleaning her apartment, cooking for herself and her son, helping her son with his homework, making the beds, and prostituting herself so that she could stay financially stable. Contrary to what one may think, the scenes involving Jeanne Dielman prostituting herself are some of the most mundane and un-erotic moments put on screen.

Chantal Akerman follows Jeanne Dielman for three days, during which time she goes about these routines in a systematic fashion, with minor missteps, such as dropping a knife while cooking dinner, occurring. By the end of the film, a significant event occurs during one of her routines, and Jeanne Dielman continues with her routines, as if nothing happens.

Chantal Akerman’s filmmaking is key in making all this work. Her camera is static and rarely cuts, only doing such when changing from room to room. The position of her camera is always a medium shot and a delicate use of mise-en-scene. The film itself runs three and a half hours long, and, in a rare positive instance; the length of the film is felt. Akerman is obsessed with time and space, and the analysis of it is a motif in her oeuvre.

Here the use of long shots and analysis of time and space emphasize the mundane livelihood of Jeanne Dielman, as Akerman shows just how difficult it is for Dielman to go about doing her chores and routines. In this sense, Akerman is fully entering into the world of a character as the daily routines are shown in their entirety versus showing short glimpses of them.

For some viewers, this can be viewed as inert, but for others it is hypnotic and mesmerizing. But there is something more going on in Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles than a woman’s chores. It represents one of the most honest portrayals of women in cinema. In comparison to the previous feminist piece on the list, Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7, which was a critique of the way the media depicts women and the shallow man’s ideas of what a woman should be, Chantal Akerman’s film instead ignores all perceptions of women and instead shows audiences a couple days in the life of the true modern woman.

There is nothing glamorous or romantic about what she does. But she has no choice, as what she does is what she needs to do in order to survive. There is a sense of grace and care to what she does, thus pushing a strong sense of femininity on the viewer. It also makes the film that much more haunting.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is an important film for film students to see, as it represents a masterful use of time and space to the filmmaker’s advantage and framing that is unparalleled. To put it simply, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is a great, little seen movie by a director who has not reached the level of fame she deserves.

23. Blue Velvet (Dir. David Lynch, 1986)

David Lynch is an enigmatic filmmaker whose films have been defined by their surrealistic nature. Often times, the films will rely heavily on dream logic, as in a Luis Bunuel film, and intentionally not make a whole lot of sense on a conscious level.

But unlike Bunuel, Lynch uses it as a means to assault the subconscious and create a nightmarish vision of Americana. Lynch wants his audiences to above all feel his movies rather than understand them. Never is this more evident than in his greatest masterpiece, Blue Velvet.

Blue Velvet is, on its surface, more coherent than some of his other works, while still remaining ultra-Lynchian. The film presents itself as a mystery, but is instead an exploration of a character. Jeffrey Beaumont, a hip college student, comes home to his all-American town after his father suffers a stroke.

While walking home from the hospital, he discovers a severed human ear on the ground. After reporting it to the police, Jeffrey discovers that the severed ear has a relationship to do with a mysterious nightclub singer and a psychopathic gangster. Before long, Jeffrey finds himself obsessed with their situation and gets too deep involved after forming a sadist sexual relationship with the nightclub singer.

In terms of mood and atmosphere, there are two key levels to Blue Velvet. The first is a campy Leave it to Beaver style Americana that exists almost exclusively during the daytime. Everything that transpires during this time comes of as cute and/or innocent. Nobody gets hurt and all is fun for the characters. This represents the plasticity of 1950s era media, and what the common man wants America to be.

Beneath it lays the second level, a nightmarishly brutal vision of the All-American town that exists, in the context of the film, only at night. During this time is when the sexual decadency and general brutality emerges. Nobody is safe in this time and real intentions emerge.

In having the two side-by-side, Lynch forms juxtaposition between desires and reality, between what America wants one to think it is and what it actually is. To drive this juxtaposition further, Lynch pits two characters against one another, who are seemingly different on the exterior. But their interior reveals that they may be more similar than they pose themselves.

David Lynch is the master of creating atmosphere and in Blue Velvet is his prime example. During night scenes, the diegetic sound that is emphasized most is the creaky ambience, so as to create an uncomfortable eeriness. This becomes more evident in scenes where a specific character inhales amyl nitrate. The scenes are lit in a very dark fashion and have a color pallet that primarily features variations on darker hues with intense Chroma.

As with the rest of the film, this is contrasted to the brighter daytime scenes, which, by design, have a wider color pallet and come off as cleaner as a result. Lynch seamlessly drifts back and forth between these two worlds as if they are one and the same.

He creates some of the most unforgettable and shocking atmospheric imagery in both segments, such as the bird eating a worm during the daytime and the candle burning as wind quickly passes it by at night. But none of this ever feels jarring or out of place because Lynch is in complete control of his film and knows exactly what he wants.

There are other aspects to Blue Velvet that can’t be discussed without entering a spoiler zone, namely the plot, the characters, and some of the more revealing imagery. As such, they won’t be discussed here. But what Blue Velvet represents is a masterpiece unlike any other. It is amongst the crowning achievements in American cinema and one of the best uses of atmosphere ever put on screen. It is a must see for all film students for such reasons. It is an experience impossible to forget.

24. Taste of Cherry (Dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

Before discussing Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, it is important to discuss everything leading up to it. Kiarostami is from Iran, of the strictest theocratic countries in the world. There they follow the teachings of Muhammad literally and use The Quran as a basis for law and punishment. Due to their theocracy, Iran is very strict about what is allowed in films, banning discussions that question or threaten Islamic powers.

By the end of the twentieth century, Iran had become home to the Iranian New Wave Movement, which is defined by a realistic documentary style of filming with a self-aware, reflexive tone. As such, an Iranian New Wave film can be described as poetic and allegorical or existential, especially in common instances in which filmmakers ask what it means to be a filmmaker.

Abbas Kiarostami is one of the central figures in this movement, and his films almost always follow the patterns and themes seen in an Iranian New Wave film/

Taste of Cherry is a minimalistic film about a man traveling through Tehran in his pickup truck. He finds three passengers, all of whom are strangers, to accompany him. During his time with the passengers, the man asks for them to cover his body with earth after he has committed suicide. Why he wants to die is completely unknown, even after the film has ended.

On its surface, Taste of Cherry is daring in that it brings up a topic that is especially controversial in the Islamic world and usually banned from discussion, suicide. And one can read the film as having subtext of equal, if not greater controversy, a homosexual picking up men. But at its heart, the film is not about either of those things and is daring for other reasons.

For one it rejects all Western ideas of how a film and story should (i.e. beginning, middle, and end with a character arc). This will upset the more mainstream viewer as it is destined and purposefully gives no satisfaction or closure. Instead Kiarostami has his audience witness distant events that they have no control over, and make them think carefully about the humanistic ideas behind them.

This forms a very unique dialogue between the director and his audience that is absent from the typical film in Western cinema. The ambiguousness for some may be baffling, but for the others will ultimately be liberating.

Taste of Cherry is a great film from one of the modern masters that, as with other films on this list, presents an alternative way of making movies. One can only hope that with coming generations, the ways films are made and told will only be pushed further to its limits.

25. The Phantom Menace Review (Dir. Mike Stoklasa, 2009)

At the dawn of the 21st Century, the Internet advanced and became a key way to pass information. With this advancement came video sharing sites such as YouTube and Vimeo. These sites commonly act as a platform to advertise for aspiring filmmakers. One such group is Red Letter Media, a production company run by underground filmmakers Mike Stoklasa and Jay Bauman. Their breakthrough film came in form of a trilogy of feature length video on the Star Wars Prequels.

The first of these video was The Phantom Menace Review. The review carefully analyzes what is wrong with the film, why, and how it could have been fixed, while also theorizing what went wrong during the production.

Within its 70-minute runtime, Stoklasa also has a story thread involving his character/narrator of the review Mr. Plinkett, a 106 year-old serial killer and the prostitute he has locked in his basement. For this reason, The Phantom Menace Review becomes poignant because of Stoklasa’s observation and pitch black, sardonic humor.

What The Phantom Menace Review represents is the future of film in general. Due the accessibility of the Internet, the review became viral and became an example of the Internet’s possibilities. In regards to the film student, The Phantom Menace Review serves as a building block for how to make a successful film and the significance of the decisions one makes when making such film.

Author Bio: Patrick DeVita-Dillon is currently a third year film student at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. He is also a major cinephile whose favorite filmmakers include David Lynch, Ozu Yasujiro, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Eric Rohmer.