10. Norte, The End of History (2013)

Running Time: 4h 11m

Norte, The End of History, running at 4 hours and 10 minutes, is one of Lav Diaz’ shorter films. He is a director firmly embedded in the Slow Cinema movement that rose to prominence in the global art cinema of the late 20th- early 21st century.

Norte, and the movement more generally, incorporates an “aesthetic of slow” in which incredibly long takes, in deep-focus, are complemented by an exaggerated lack of movement from the characters, the environment, and the camera itself; the film brings to the forefront the temps mort of European art cinema to the point where it becomes the key structuring principle of the aesthetic.

Diaz tells the tale of a passionate, yet disaffected, student Fabian who decides to murder an unscrupulous money-lender in a misguided attempt at revolutionary violence. The murder is subsequently blamed on Joaquin, a down-on-his-luck construction worker, who ends up being wrongfully convicted for the crime and jailed for life.

The film, with a distinctively meditative pace, then follows the two men as they attempt to come to terms with the consequences of this cataclysmic set of events. Joaquin is able to retain a sense of humanity, and compassion despite the constant threat of violence that accompanies prison life. Meanwhile guilt slowly gnaws away at Fabian’s psyche; his fruitless attempts at redemption find him wandering across the Filipino landscape like a modern-day Raskolnikov.

The film’s ascetic approach to storytelling can be off-putting to some, and indeed it is a difficult piece of cinema. Yet it rewards patience with a visually stunning, philosophical piece that skilfully interweaves the quotidian with the deeply spiritual.

9. Kwaidan (1964)

Running Time: 3h 3m

Kwaidan is a film of such sumptuous beauty, and stylized set-design that it is hard to believe that it is considered as a classic of the horror genre. And indeed to even attempt to classify it as a genre-film would be a far too reductive approach to Masaki Kobayashi’s wonderfully distinct work.

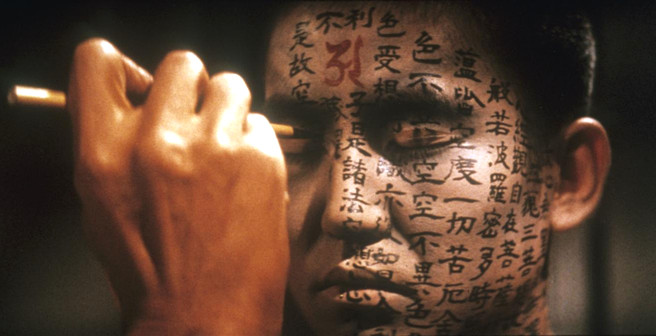

The film consists of four stories, all set within Japan’s archaic past, that deal in some way with ghosts. The first ‘The Black Hair’ concerns a swordsman who leaves his wife in order to marry into a more prosperous family; his eventual repentance and return to his first wife results in an ending that is as chilling as it is mournful. The second and third tales, ‘A Woman in the Snow’ and ‘Hoichi the Earless’ contain some of the most beautiful set design ever committed to film.

A particular memorable scene in the second story portrays a snow-covered forest on a dark night, in which the painted background substitutes an image of the moon with the disturbing, glassy-black pupil of an eye. The film’s only disappointment is the relatively lacklustre final tale, ‘In a Cup of Tea’ that lacks both the beauty and creeping terror of the previous segments.

That the film has a more melancholic approach to the ghost story is reflective of the fact that Japanese cultural, mythical, and religious conceptions of the spirit world are markedly different from popular Western ideas; Japanese ghost stories always mix a sense of unease and horror with the theme of great personal tragedy.

This has resulted in a cinematic tradition that includes such supernatural classics as Ugetsu Monogotari and Dark Waters. None, however, reach quite the aesthetic heights as Kwaidan. It contains a rich, and deeply cinematic, beauty that will continue to astound for generations to come.

8. Intolerance (1916)

Running Time: 3h 30m

It is utterly mind-boggling to watch Billy Bitzer’s crane shots that tower over the enormous reconstruction of Ancient Babylon and consider that such a cinematographic feat was pulled off about a century ago. A sense of formal and thematic experimentation is evoked as soon as D.W. Griffith’s epic film begins, with intertitles that explain that the film will move between four stories all linked by the theme of intolerance. This is a film made in 1916!

The four segments include a tale of institutional corruption and organised crime set in contemporary America, a depiction of the events leading up to the St. Bartholomew’s Massacre in Renaissance France, segments of the life and death of Christ, and the story of the fall of Babylon to the Persians in 539 BCE.

The segments certainly aren’t given equal weight; the sections in France and Judea largely fall by the wayside as director D.W. Griffith revels in his giant Babylon set like a kid in a playground while the story in contemporary America is given the most intricate, and developed plotline. While there is an evident imbalance, the thematic and narrative links that bind the stories together are evoked with a real stylistic flourish.

Intolerance is an important film in the history of cinema, just as Griffith is an important director. The film is an early example of lavish, highly ambitious cinematic spectacle; a medium-defining work that contains action sequences that match, if not better, the efforts of contemporary blockbuster cinema. This all sounds like hyperbole, but the film genuinely needs to be seen to be believed.

7. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Running Time: 3h 45m

So many adjectives are thrown out about this film in order to avoid describing it as ‘dull’; there’s ‘hypnotizing’, ‘mesmerising’, ‘strangely compelling’, amongst many others. But the film is dull, and that’s ok. It’s supposed to be dull, Jeanne Dielman is a reflection on the nature of dullness, on the plodding monotony of everyday life, on the way in which the eponymous protagonist is undone by the oppressive weight of time itself.

The film is a hyperrealist masterpiece about three days in the life of a single mother. Jeanne, played by legendary French actress Delphine Seyrig, has a routine that structures her life: she wakes, dresses, makes breakfast, wakes her son, sends her son to school, cleans the kitchen, buys dinner, babysits for her neighbour, has sex with a man in exchange for money, and makes dinner for her son.

Director Chantal Akerman portrays these events with painstaking temporal realism, in extremely long takes, as we wait with Jeanne for a kettle to boil, wait with Jeanne in line at the post office, and wait with Jeanne as she sits in preparation for the company of one of her clients.

Akerman’s is an aesthetic of monotony; her intelligent stylistic design lulls us into a soporific appreciation of Jeanne’s routine so when the most minute of disruptions occur, the audience immediately take notice. This is where Akerman’s genius really shines through; a strange, almost imperceptible disquiet creeps into the frame during the last day that we observe Jeanne: a spoon drops, a shot is framed slightly differently, cuts between shots spike suddenly and briefly in speed.

Akerman’s remarkable achievement is to make this slight disharmony feel monumentally ominous as the film approaches its chilling finale. Rightfully regarded as triumph of feminist filmmaking, Dielman is also an intelligent experiment with the very language of cinema itself.

6. Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Running Time: 4h 11m (Restored Version)

Once Upon a Time in America has been saddled with a similar burden to Scott’s Blade Runner, in that there are so many versions of the film (released and unreleased), with such enormous disparities in running time (from 139 minutes to 251) that is hard to know where to go to find the truest version of the film that was to be Leone’s last. The version that will be discussed here runs for 229 minutes and served as the European theatrical release.

It would be wise to find the longest version of the film as possible, as there is great pleasure to be found in immersing oneself in Leone’s vivacious, violent, grubbily beautiful evocation of Manhattan’s Lower East Side in the 1920’s, 30’s, and 60’s.

The film follows a gang of friends, led by De Niro’s Noodles and James Woods’ Max, as they rise to prominence in New York’s criminal underworld. It is an epic, turbulent tale that write the history of Prohibition-era America in smears of crimson across a sepia-toned canvvas.

While Scorsese covers a similar period of time with his own sprawling crime saga, Goodfellas (1990), he does so with frenetic pacing, tearing through decades of Henry Hill’s life with narcotic glee. Once Upon a Time, conversely, is a slower, more meditative work that examines the weight of time as it transforms, strains, and breaks bonds of friendship, loyalty and love.

Like The Leopard, the film weaves an intimate, melancholic tale into the history, and mythology, of a nation. It is far more than a tale of tommy-guns and bootlegging, it is a study of the way in which relationships are forged and broken in the snarling, brutish, hyper-masculine culture of gangsterism. Once Upon a Time is a devastating masterpiece, sporting one of De Niro’s greatest performances.