6. Deep Red (1975, Dario Argento)

Giallo are, as a genre (or subgenre, or movement, or cycle…), some of the unsung heroes of the movies. As another example of a rigidly structured genre whose main purpose was to have its own rules tinkered with, directors like Mario Bava, Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, and even Michele Soavi thrived as “auteurs” in an area that did not require them; trashy horror.

More viscerally fun than deeply haunting, these movies created the American slasher by expanding upon the 60’s Hammer horrors using Italian thriller novels as their source. Argento’s game was making expressionist movies, and Deep Red is the embodiment of it. Paintings serve as literal settings, bathed in absurd, unrealistic colors.

Through the noise of emotion, Argento toyed with the typical horror tropes (the boo-scares, the falling heroine) to create an entirely new idea; inflicting a combination of fear and fun by way of impressionism. The flow of the audience’s emotions is paramount, not the plot structure.

One could dive into the entire world of giallo (and eventually neorealism, should they venture into Visconti), branch out to the spaghetti westerns that these directors also occasionally made (Argento co-wrote Once Upon a Time in the West), or venture into impressionist forefathers like Jean Cocteau, based on the links from this movie alone.

It’s unfair to a great movie to think that it doesn’t warrant a serious discussion because of how fun it is. If the point of a movie is to connect to the audience through images, sound and motion, then Dario Argento, even if only for part of his career, cut through all of the unnecessary fluff to reach that audience; he used their fears against them.

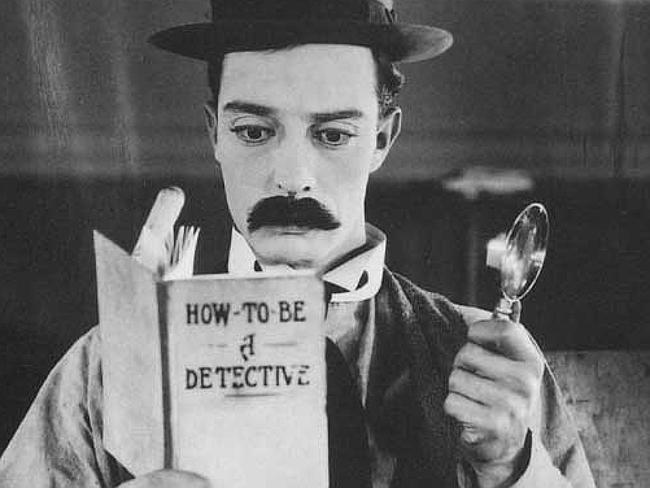

7. Sherlock Jr. (1924, Buster Keaton)

Buster Keaton used the danger of physical peril instead of words to distill a similar gut reaction. There’s no red tape with comedy. Keaton was more of an experimenter as a director than Chaplin was.

Chaplin loved those clean frames that allowed the Tramp to do his thing (much in the same way that Judd Apatow chooses the best improvised takes from his actors, who can endlessly riff in front of a planted camera). Keaton was more of an Edgar Wright, who used the medium itself to tell the jokes as much as the actors.

He also excelled at risking his own life to get a laugh. In the movie, his character jumps into a theater screen. It just so happens to be a shot of a mountain cliff; thus, Buster Keaton must (in reality) jump off a cliff and hang on for dear life. As in, in the world we live in, he did that.

In The General, he pulled a similar stunt on the front grill of a real moving train, where he used a wooden beam to knock another wooden beam off the railroad. Say that stunt didn’t work on the first take. He would have done Take 2 from a hospital bed.

For anyone who has seen the final credits of a Jackie Chan movie, they should know that an important difference between the two of them is that Keaton couldn’t have had the blooper reel. Sherlock Jr. is as much a thriller as it is a comedy. From there, the door to silent movies are flung wide open.

8. Rolling Thunder (1977, John Flynn)

Major Charles Rane is really The Terminator, sent from the past to seek revenge on those who murdered his family. He is part superhero, part antihero. He is, in no way, a good guy; he will kill every thug unfortunate enough to be between him and the job. As a single movie, it functions as a top tier action flick, a character study, and an honest examination of PTSD. As part of a family, Rolling Thunder is a weird little hub of many different kinds of 70’s Hollywood movie making.

As part of the New Hollywood family, Rolling Thunder experiments a bit with narrative flow, beginning at a point typical of a classic movie, and ending, unusually, mere seconds after the climax. It is one of the first movies that looked at the Vietnam War in terms of its after effects – the boys coming home – and one of the only genre pictures to do so. Rolling Thunder was made just after Taxi Driver and just before Apocalypse Now and Deer Hunter, so the producers didn’t really know what to do with this action movie.

They billed it as a grindhouse picture, which makes it one of the more polished ones ever made, because it was actually an A-movie in disguise. The opportunity afforded to such a picture, then, was the ability to be simultaneously a serious film and a badass movie.

9. The Oyster Princess (1919, Ernst Lubitsch)

You’ve seen “Lubitsch” on almost every Greatest Directors list, but you always find a reason to get around to one of his movies later. Because seeing Trouble in Paradise, Design for Living, or Heaven Can Wait on these lists can be a bit repetitive, you will be watching a celebration of sex, jokes, and joy itself, Die Austernprinzessen.

Actress Ossi Oswalda was huge in Germany at the time, in large part because of her physical style of acting. She doesn’t shake hands; she jerks them. She slaps backs and scales walls and throws chairs and cannot be contained by the frame in which the camera places her. She asks a waiter if he knows the foxtrot, who says he does. You’d think the punchline would be her throwing away the tray in his hand to dance. But she smacks it out at full force, as if trying to get the actor to break character.

This is all in the middle of a segment that interrupts the movie to show a metaphorical orgasm; a foxtrot breaking out during a wedding. The hundreds of guests suddenly start dancing, and so do the hundreds of servants and cooks. The maestro convulsively conducts the orchestra, whose instruments include slapping a man’s face to the rhythm.

The maestro’s wand is a penis, and at climax, it explodes in a cloud of smoke and glitter. This has nothing to do with the plot; Lubitsch just wants you in ecstasy.

His later talkies, made in the states, came to full maturity with the addition of Samson Raphaelson as frequent screenwriter. The formula of using inference, repetition and substitution to describe society’s restrictions on the libido was largely responsible for what is now mythically labeled The Lubitsch Touch (Neal, p. 152) . But before it was fully developed, audiences got a once-in-a-generation opportunity to see a master at his most unbridled.

Lubitsch touched so many areas of filmmaking through his rom coms, that he could be considered both the journey and the destination. His movies inspired Wes Anderson and haunted Billy Wilder. His contributions to German Expressionism could be included in the early influences of film noir, whose effects can be felt to this day. The Oyster Princess is as fun an entry to silents as one could get, and is as potent a comedy as one of the few great comedy directors ever made.

10. Come Drink With Me (1966, King Hu)

Peter Trist said it best. “King Hu… is arguably the most underappreciated ‘great’ director in world film history.” This might only be because he made martial arts movies, which are similarly among the most underappreciated ‘great’ genres. Come Drink With Me is the combination of just about everything westerners don’t know about China.

Its story is based on a wuxia novel, which is a kind of literature that’s existed for roughly 2,500 years. King Hu borrowed the visual style from Huangmei opera movies, an unfortunately short-lived Hong Kong movie subgenre. He refined, if not reinvented, the standard of special effects common in Hong Kong action movies of the previous thirty years (obvious wires, playing film in reverse, hokey animation drawn directly on film to show palm power and lasers). And he balanced the overall product, neither solely a martial arts vehicle, nor a straight drama.

Hu, and his contemporaries like Chang Cheh, were imitating the samurai movies like Kurosawa’s, and tailoring those stoic cameras to Chinese tastes. They even brought in top crew members from Japan to helm their projects.

The Japanese had a long tradition of still cameras that emphasized complexity in composition, and not camera movement, due to live narrators for silent movies. Hong Kong both did not have this tradition, but did have a major influence from Hollywood because of its western influences. In Come Drink With Me, this history lesson comes together in revelatory fashion.

Still cameras present a technicolor photograph comprised of men and women in a standoff before the fight. Even when the fight starts, the cameras hold and the audience squirms. The slight release, a single camera shift, a quick cut, creates staccato action in a flowing battle. The camera stops, the characters shift. Weapons are tangled in a lock. The hero needs better footing.

The deadly silence before the next action shows even further restraint from the sound mixers, who easily could have cued the audience in by the typical clangs and chings of swords trying to untangle themselves. It was a smart move for Hu not to change the status quo of hiring dancers to play the action leads.

The hard, sharp punches and kicks from the future kung fu movies would require martial artists. But the swirling swords, bending bodies and elaborate choreography required the grace of a ballerina. Which he got in Cheng Peipei as the lead. Her fury was a bonus. Cheng is an invincible demigod in Come Drink With Me, the stuff of legend. Tarantino was smart to steal from King Hu. When you fall in love with something beautiful, don’t you want to share it with the world?

References:

Steve Neal on Ernst Lubitsch – https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ZTyLBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA151&dq=related:CSb80eDfhYeRrM:scholar.google.com/&ots=NDoRBmIbUs&sig=ngZyhkDZWj2CX7XECsRWwW7Xrlk#v=onepage&q&f=false

Peter Trist on King Hu – http://offscreen.com/view/touch_of_hu

Author Bio: Patrick works full time in childcare. He spends his free time pursuing adult hobbies, such as writing about his favorite movies.