14. Hour of the Wolf

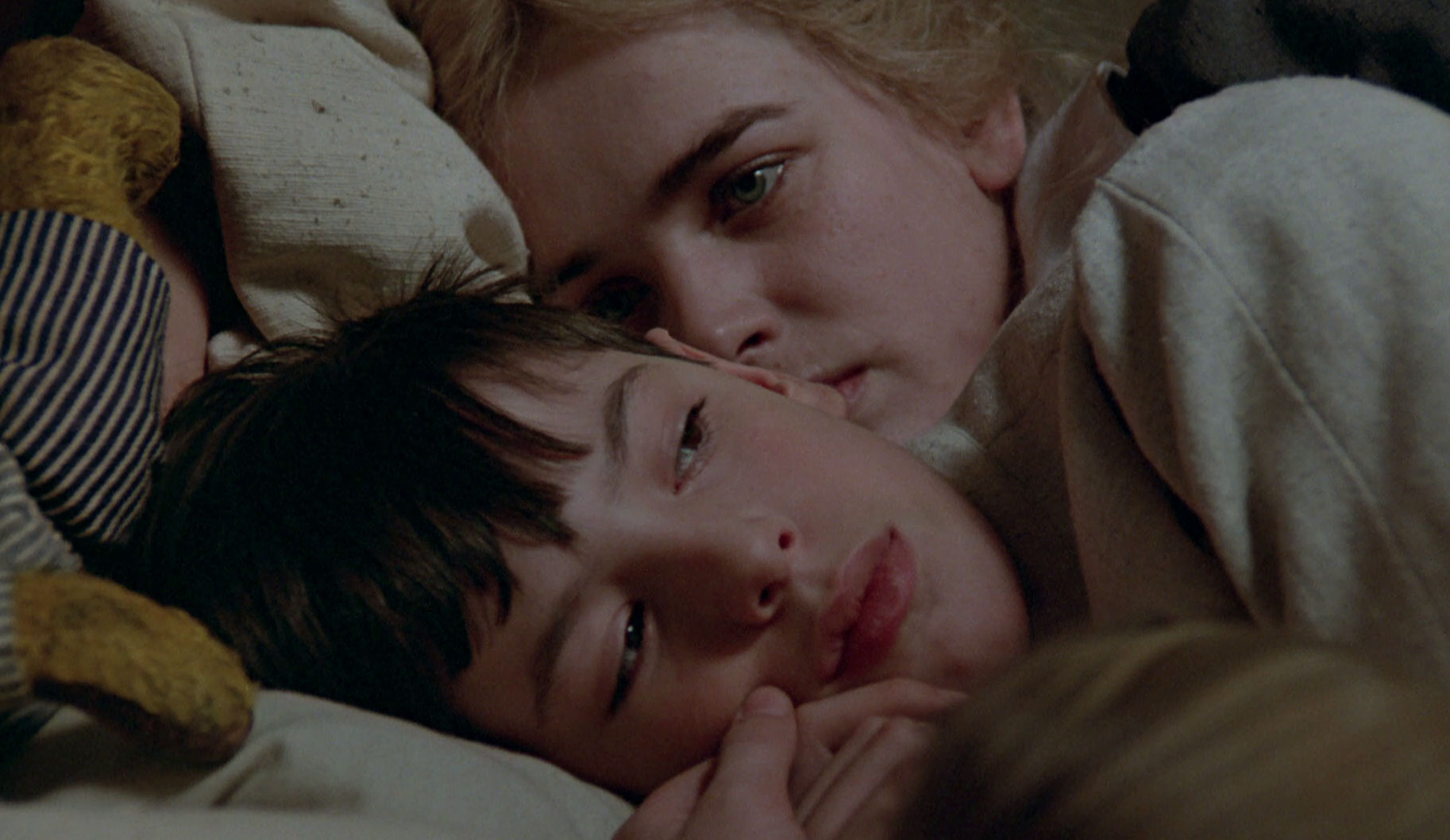

Widely known and recognized as being the only intended horror film in Bergman’s filmography (although quite a few other films of his certainly could be approached as borderline into the genre), Hour of the Wolf is a sacred spot in his career. Filmed with a pregnant Liv Ullmann carrying Bergman’s child, the comparisons between character and creator just merely begin to blend.

Sydow’s “Johan” is certainly a stand in for the artist Ingmar Bergman himself and the whole scenario reflective to Bergman’s own inner torment materialized for the screen. This is the core essential to the surrealistic nightmare that unfolds that it is all metaphors for a creative sometimes mental struggle that artists face when becoming so fully immersed in their work.

Reality and fantasy blur and the thoughts of a crazed genius return to haunt the man until they engulf his entire being. Bergman reaches new heights in torturing the human psyche and he succeeds here.

13. Prison

Prison is a film that on the surface seems very easy to write off as being a lesser work from Bergman. It is only his sixth feature film and still among his 1940’s outlet. Yet when viewed, you can easily see and experience a greatness and wisdom that back in 49′ should have been a miraculous sign that an auteur was born.

What Bergman has crafted here is an experimental morality play with even the title playing a part in the film’s meaning. It is called Prison but not in the sense of confinement for criminals but rather a imprisonment of the soul within the human body. It is a extremely dark film whose largest theme examines the bleak nature of our world and describing earth as the living breathing Hell.

Suicide is a topic that is nearly always mentioned and in that area is where the title really commands its power. The living carcass that houses our spirit when there is nothing else worth living for in this hell of a world, that is when one wants to break free from the prison.

It is also fascinating to see Bergman so experimental this early in his career. The film begins immediately within a film set where the audience has a peek into the inner workings of filmmaking. This is followed by the director within the film being pitched an idea for a movie from his recently institutionalized professor. From here on we go from one character to the next witnessing the path in how they are related and being introduced at the same time.

It is not until a little over 10 minutes into the movie that the opening credits appear except that they do not appear. Bergman instead opts for off screen spoken narration of the cast and crew and even how far along the story resumes in replace of standard on screen text. He does not stop there as later on in the film with a pre- Wild Strawberries inspiration, he crafts a hauntingly effective dream sequence with a forest made out of people and symbols of regret involving an infanticide.

Including the dream sequence, Bergman’s richly layered film also explores the fear of being alone and the constant approach for human connection in all forms. We get this not only through the suicidal man but even his befriending of Birgitta Carolina (who also craves connection into her forced prostituted life). Prison is such an underrated film in Bergman’s canon and one that could even contend with some of his best.

12. Summer with Monika

So as history goes Summer with Monika is a filmed sonnet, a love letter if you will to Harriet Andersson. Bergman fell in love with her and hence did the camera. As Bergman was busy glorifying Andersson into not only an erotic object but symbol of independence for women and defiance against the male dominated society. He actually changed at that point in his career into viewing the film (his films to come) from a female perspective and a female protagonist.

History also speaks that when this film was originally released and due to its few short scenes of nudity for the time period, it was re-edited and marketed in America as a film in the same boat as Russ Meyer trash cinema. When it was finally re-released in its proper form, it was highly praised and considered a gem in Bergman’s canon.

Even Godard was a big fan and wrote a excellent review on the film comparing it with such influence as D.W. Griffith, he said specifically: “It is to cinema today what ‘Birth of a Nation’ is to the classical cinema.”

11. Sawdust and Tinsel

Pronounced in the opening credits as a broadside ballad on film, Sawdust and Tinsel explores the extent of human humiliation more so than in any other Bergman film (in fact it’s the film’s main theme). This also marks a turning point in Bergman’s career featuring the first of many legendary collaborations between Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist and also a staple for his creative freedom to come.

Sawdust and Tinsel is also one of Bergman’s darkest films and the famous opening flashback sequence featuring Frost the Clown has been cited by film aficionados around the world as some of the most depressing material put on film. It is actually quite brilliant of a choice for Bergman to open the film on that note for the rest of what is to come.

The story of Frost, the brigade of soldiers, their phallic symbols of firing canons, and the humiliation suffered from his wife’s actions put into perspective this great theme on the human condition of dignity and pride. A cowering Frost still dressed in his clown makeup stands undressed at the shoreline ready to retrieve his wife when the soldiers laugh at his misfortune.

To achieve laughter is what his profession calls for so Bergman inserts this double standard of what it means to laugh in jest and to laugh in humiliation. What really makes the film of Sawdust and Tinsel so unique and amazing among his earlier works is the dynamic of characters and the limitless feat he tries at testing them to their very being.

Again it is a brutally dark film and the range and transformation of its characters all the more cements this fact. This is Bergman really coming into himself and perfecting his moniker as the Swedish miserablist. One of his best films from his earlier period.

10. Summer Interlude

Bergman’s visuals alone can evoke emotion within a viewer, whether it be nostalgia, melancholy or sweet joy at a summertime romance. Summer Interlude is criminally underrated amongst his already hyperbolic body of work (in that sense it is easy to see why it is so often passed up when describing his best films but still needs to be recognized).

Perhaps one of the greatest aspects about Bergman is how easy he can channel not only human emotion and our very nature and being. So when crafting a story about a doomed love affair (not even close to being the first time he has encountered such subject matter either), he still manages to mold an entirely original and engaging piece that feels all too real and effecting.

9. Fanny and Alexander

What many perceive as Bergman’s magnum opus due to its size and epic scope in the grand story it tells. Fanny and Alexander is magical filmmaking at some of the most heightened states it can take the medium.

Featuring one of the few times that Bergman centers his film around a child protagonist and focuses the viewpoint in their own, it is no wonder the film looks so fantastical at times as seen through the imagination and wonder of a young boy (most likely representing a young and creative Bergman himself during his childhood).

The familial drama is master class and follows a steady progression that is almost akin to a Greek tragedy. The ill fortune which brings a family to its knees and a menacing force that replaces it at the throne of what once was a vast kingdom of love and warmth. The overbearing pastor figure is extremely parallel to Bergman’s own life as his father too was a strict pastor at the head of his household.

Fanny and Alexander is journey through some of the brightest and darkest moments of Bergman’s work and can be easily recognized as being among the best he has crafted.

8. Cries and Whispers

Probably Bergman’s most famous film as far as critical success is concerned, garnering him many of the major global awards. It also features three of his top regular actresses in one film with Ingrid Thulin, Liv Ullmann, and Harriet Andersson. If only he could have gotten Bib Andersson a role in here as well then it could have been a Bergman fan’s dream come true.

As it stands, it already succeeds as a dream come true for cinematic experience. A blend between Nykvist’s haunting cinematography, Bergman’s color aesthetic using crimson red as a metaphor for the soul and certainly his story of desired acceptance and sought after love even from beyond the grave.

He crafts drama within this one to its fullest potential during the claustrophobic interactions among the women who seemingly appear entrapped in the manor, a place of history and lies. It is safe to say as it is widely recognized that Cries and Whispers is regarded as one of Bergman’s best. It’s essential; in fact it is more than essential, it is one of his defining films for his career.