7. They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969, Sydney Pollack)

What makes it depressing: Life as a perilous endurance contest.

Jane Fonda, and many others, enters into a dance marathon contest during the Great Depression, hoping to earn $1500 after over a month of continuous dancing. Upon entering the contest, Gloria, played by Fonda, is already bitter, sniping at nearly everyone who speaks to her.

During the course of the marathon, one man suffers a stroke and dies, his partner loses her mind—she enters the shower, fully clothed, and stares at the shower head which distorts her face; the most captivating shot of the film—even a pregnant couple is desperate enough to enter the contest; it is the Depression after all.

The marathon serves as a metaphor for live itself during those awful 1930s. People were so impoverished and needy that they agreed to subject themselves to such physical and emotional duress over what even in 1969 must have seemed like not that much money. But that’s how life goes; you put up with all the little indignities, the attacks, stresses and pains, and then it’s mercifully over.

Upon learning from the organizer that the event is rigged—the winners get basically nothing after having to pay for a month’s worth of food and laundry—Gloria and her partner immediately drop out of the contest. Exhausted and depleted, Gloria and her partner Robert, a gentle and obliging man, lean against the boardwalk. Gloria asks Robert to shoot her in the head; she’s had enough with this useless existence. He agrees; after all, once a horse is too old or lame to be of use, they put them to bed with a pistol, don’t they?

That reasoning is so dreary, that a human being is no more valuable than a horse, that a person’s life is so expendable that it can just be extinguished once it has run its course. But isn’t it justified? Can you really blame someone for retiring from what had been a completely awful life? Is that so criminal?

6. Come and See (1985, Elem Klimov)

What makes it depressing: The madness of war.

Floryan is a young boy of about twelve living in rural Russia. The film opens with Floryan and a friend playing around on a beach, looking for lost World War II equipment. The Soviet army comes calling during World War II, and Floryan, after finding a rifle, answers the call, wanting to help ward off the Nazis, despite the cries of his mother that he is not ready for combat. Floryan quickly realizes that indeed he is not ready; he becomes lost from his platoon, a succession of air raids leave him partially deaf, the Nazis slaughter his entire home village, and he is left to roam the mud-filled woods injured and afraid.

The pure devastation of war is encapsulated in Floryan. Little things, such as Floryan’s hat appearing far too large for him, his failure to notice the huge pile of his dead friends and neighbors as he abandons his home village, his trudging through the mud to symbolize the emotional struggles he must push through, work to prove that the hell of war is no place for the innocence of youth.

The film spans only a handful of days, but by its end Floryan appears an old man, his skin cracked and covered with mud, blood, tears and bruises. After watching an entire church filled with his countrymen burned to ash, the Nazis finally move on, leaving nothing but death behind.

Floryan finds a framed photo of Hitler in a small puddle, and fires his rifle angrily at the photo. Floryan imagines a Nazi rally, and fires again. He imagines Hitler during World War I, another bullet. He imagines Hitler as a university student, another bullet. But can he bring himself to shoot Hitler as a toddler? Has the war filled him with that much hate, or is there something of his humanity left? Either way, Floryan view of the world is forever shattered.

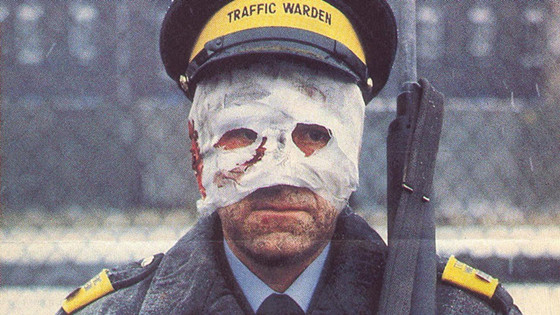

5. Threads (1984, Mick Jackson)

What makes it depressing: The destruction of nuclear holocaust.

What if, during the Cold War, a large nuclear warhead were to be detonated over a large metropolitan area? What would be the results? What would it look like? This film gives a pretty shattering, dreary, but realistic depiction of just how horrible that scenario would be.

The story follows several families in Sheffield, England before and after the outbreak of global nuclear war. One young couple is pregnant, another is living out their golden years. After the bomb, after buildings collapse, radiation sears the flesh and poisons the air, and the skies are made permanently dark with gas and debris, all that is left is to try to cope and survive.

The elderly couple scraps for one more can of food before they succumb to radiation poisoning. The pregnant couple fears for the health of the baby, and lives in dread of mutations and birth defects. While scavenging, the young man sees a woman shaking, unable to move or speak, holding her dead baby, surrounding but rusty, jagged rubble. The safe life of football, apartment hunting and family dinners has been replaced by a nightmare.

The entire webbing of society is destroyed. There’s no government to provide assistance, offer food rations. No hospital staff, no electricity, no clean water, no growing crops. In short, there is virtually no hope. Any life that survives this holocaust will be short and miserable.

4. The Road (2009, John Hillcoat)

What makes it depressing: The desperation of a post-apocalyptic world.

The story is simple (based on the novel by Cormac McCarthy which won the Pulitzer Prize): a father and son try to survive after some unexplained global catastrophe. Yes, there’s the constant fear of marauding thieves or cannibals, who will do anything to try to survive. No trust of anyone or anything. But what really makes this film so devastating is the way it’s shot. Lots of blacks, grays, and browns. No color, no sunlight, no vibrancy whatsoever. No hope. There are many long takes, which cause you to hold your breath in fear and anticipation of what danger lurks around the next abandoned building.

There is no explanation as to how society dissolved. We can ruminate about nuclear wars, energy or food shortages, diseases, natural disasters, but it would all be conjectures. The fact that there is no justification gives the apocalypse a sense of naturalism. There wasn’t a mistake, a human error that brought about the end. This state of primitive survival is the natural way.

One of the more trying scenes is where the father and son journey to the father’s childhood home. The father tries to explain to his son, who was born after the catastrophe, what life was like when things were good. When we had Christmas dinners, television, and safety. Knowing that his son will never know any of these comforts is almost too much for the father to bear.

3. We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011, Lynne Ramsay)

What makes it depressing: A mother’s grief, and one of the most appalling acts imaginable.

Kevin is a troubled young boy, and has been since he was a young child—he wasn’t fully potty-trained until about seven. He would constantly makes messes and be a rotten child, with the apparent intent solely to irritate his mother.

Yes, it’s true that Kevin’s mother isn’t perfect—there are times she regrets not travelling more before motherhood—but she’s still a loving and caring mother, despite Kevin’s behavior. How does Kevin respond? He kills his father and little sister before locking himself in the gymnasium of his high school and murdering several classmates with a bow and arrow.

The film is edited non-linearly; we see some of the aftermath of the massacre—the mother dealing with the grief, other community members treating her like a pariah, kids vandalizing her home with blood-colored paint—before we learned what actually happened. We see the hell the mother is going through at the hands of her child, her attempts to cope.

By editing the film this way, we are left to ponder, What could she have done? Short of having the child committed to a mental institution, and who knows if that would have been possible—Kevin acted every bit of normal around everyone but his mother—could this tragedy have been averted? Or was Kevin simply a bad child to his core?

Again, we see the inability to prevent tragedy. Kevin’s mother knows he’s a potentially-dangerous brat; she sees the writing on the wall. But she doesn’t want to admit that she birthed this monster, so she does nothing, hoping that two loving, attentive parents can fix his problems. That is the hope, but this world requires a bit more than hope.

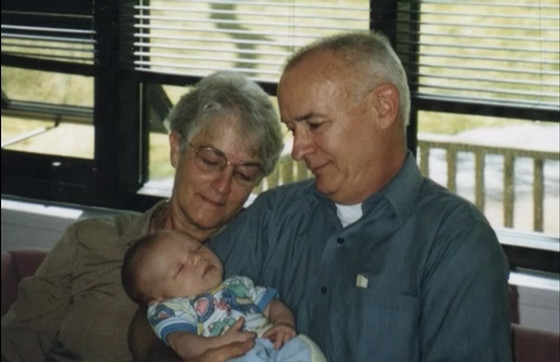

2. Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son about His Father (2008, Kurt Kuenne)

What makes it depressing: The inability of the law to protect us.

This film is a documentary made by Kurt Kuenne to commemorate the death of his good friend Andrew Bagby. Andrew left this world not knowing that his ex-girlfriend was carrying his son Zachary. This documentary was meant to be a summary for Zachary of who his father was. Zachary will never watch that summary.

Zachary’s mother was a woman named Shirley Turner. All the evidence surrounding Andrew’s death, which is too long to list here, points to the conclusion that Shirley murdered Andrew, and she was officially charged with the murder. However, due to circumstances such as Shirley’s pleading to the judge and the slowness of the Newfoundland court system, Shirley, an accused first-degree murderer, was released on bail and given custody of her months-old son.

Andrew’s parents, David and Kathleen, fight for custody and visitation of Zachary the entire way, which means they must plead the Canadian government to spend time with the woman who murdered their son. They abide this horrible injustice, all to keep their grandson safe as Shirley goes in and out of courts and jails.

All their work, putting up with this horrible woman who had done something so evil to them, was for naught; Shirley leapt into the Atlantic Ocean, with little Zachary strapped to her chest. This tragic death of the most innocent and gentle of human beings could have been easily avoided, as the Canadian government has officially acknowledged, if Shirley’s crimes, and her professionally-diagnosed bipolar disorder, has been properly managed.

By our seemingly-incurable inability as humans, both through our governments and as individuals, to seek and provide proper treatment to and understanding of the criminally and mentally ill, is what led this unthinkable crime.

1. Requiem for a Dream (2000, Darren Aronofsky)

What makes it depressing: The apathy and lack of concern shown by everyone.

A plethora of different drugs conspire to bring down Harry Goldfarb, his girlfriend Marion, best friend Tyrone, and mother Sarah. At first, the drugs promise the allures of money from their sale, the relaxation of the party atmosphere, the fitness of diet . But the fact of addiction makes the usual dosage never enough, and the effects get progressively worse.

Drug addiction is a terrible thing. We all know that, and we have all seen in various other films the horrors of withdrawal, needle infections, of the hard life of the crime for those who deal the stuff. What is rarely discussed is the social stigma, the alienation of those addicted.

Sarah wants to lose weight, so her doctor, who can’t take the time to look her in the eye, puts her on a medley of diet . Even when she comes in later, clearly out of it, mixing the scripts, the doctor is still too preoccupied. Marion sells her body and soul in front of business men only concerned with seeing her strip and getting off; they don’t even notice her track marks. Harry and Tyrone head from Brooklyn to Florida in search of dope to sell. They wind up in prison in North Carolina. Racist cops and guards assault Tyrone, and unsympathetic doctors amputate Harry’s badly-infected arm. These four had no one in their lives they could turn to for help.

They couldn’t go to a hospital without fear of being arrested, which happens to Harry and Tyrone. No friend. No social worker. Not a single soul cared for them, had their health in heart. Everyone saw them as lost causes, lepers eaten away by a drug. Do not help; avoid at all costs. They clearly need help, but we must not help. That is what drug culture in America has become.

Author Bio: Dylan Rambow studied film and journalism at Northern Illinois University. You can read his other film reviews at dylanonmovies.blogspot.com.