Portuguese cinema essentially refers to films directed by Portuguese filmmakers. Cinema was introduced in Portugal in 1896, and the first Portuguese film was a replica of the Lumière Brothers’ inaugural presentation about six months earlier. Portuguese cinema had, throughout its history, various phases which have always made it a very distinctive case within European cinema. In the 1930s, with the advent of sound films, spoken content was used for defending morals and to serve as propaganda for the dictatorship that ruled Portugal from 1933 to 1974.

Starting in 1933, with “A Canção de Lisboa,” the Portuguese Golden Age would last for the next two decades. In 1942, Manoel de Oliveira’s first feature film predated Italian neorealism by a few years with its realist style. In the 1960s, a Portuguese avant-garde film movement was born during the dictatorship, breaking away from the prevailing ideology, and showing realism in film in the vein of Italian neorealism and the French New Wave.

The above-mentioned time periods are represented on this list by some of Portugal’s best directors who, in a broader perspective, capture the Portuguese mood and people, as well as the various genres and styles—from the “Golden Age” to the most recent accomplishments.

20. ‘Non’, ou a Vã Glória de Mandar / No, or the Vain Glory of Command (Manoel de Oliveira, 1990)

In 2008, at 100 years old, Manoel de Oliveira was reported as the oldest active film director in the world.. He’s undeniably the most celebrated Portuguese filmmaker, directing over sixty films, and the only one whose active career has spanned from the silent era to the digital age. Thus, disagreements may transpire over his most meaningful projects, but I feel the ones included on this list capture his filmmaking with consistency.

No, or the Vain Glory of Command is based on the history of Portugal and presented through the voice of a soldier from the 1974 Colonial War. A group of Portuguese soldiers are on a military mission in Angola, and they ponder their purpose for fighting; one of soldiers discusses several episodes in Portuguese history in which Portugual has suffered failure and defeat throughout its existence.

The film is fragmented with flashbacks from tho soldier’s stories, intensifying its nostalgic feel, and combining it with a contemplation of the entire history of Portugal.

19. Jaime (António-Pedro Vasconcelos, 1999)

António-Pedro Vasconcelos was responsible for some of the most commercially successful films in Portugal, including this one.

Jaime is the story of a thirteen-year-old boy whose mission is to reconcile his parents separation, which eventually leads the audience to the main theme of the film: child labor and exploitation. His parents are poor, and unbeknownt to them, Jaime decides to get a job with a schoolfriend, hoping this will solve his parents’ problems.

Recently, the movie has become somewhat of a cult film, and oftentimes, my family still tends to quote from it. Shot mainly on the city streets at night, the film perfectly captures the city of Porto and its lower-middle class, adding a special tone to it. Essentially, Jaime depicts the transformation of an innocent child to tough, little man. The boy withstands extremely dark ordeals whilst the spectator is permitted to visually experience each disaster, building up to the ultimate emotional “kick” at the end of the film.

18. Aquele Querido Mês de Agosto / Our Beloved Month of August (Miguel Gomes, 2008)

One of the movements adopted by Portuguese filmmakers at the end of the 20th century was docufiction—a genre that consists of documentaries combined with fictional elements, which is mostly based on Italy’s Neorealism and the French New Wave.

Our Beloved Month of August is primarily a comical docufiction depicting the rural side of Portugal. At first, the filmmaker Gomes searches for directiondirection through stories and interviews, as well as filming spaces and capturing natural sounds and traditional bands. The first hour is mostly pure documentary, whilst seldomly revealing its fictional side.

The film appears improvisational, as if the cameras were just let to roll. It’s not until well into the film that the audience witnesses the fictional components with only tiny facets of documentary style filmmaking. Although there is an interesting part that portrays teenage love and family issues, the film’s mixture of humor, community, and location makes it exceptional. In search of uniqueness, the mood shifts regularly, and receives the bonus points for the outstanding joke at the end.

17. No Quarto da Vanda / In Vanda’s Room (Pedro Costa, 2000)

This docufiction, which explores social injustice, is the second in a trilogy of films by Pedro Costa.. All three films are a must-see, but. In Vanda’s Room is possibly the one with the most disturbing outlook on the lives of the miserable during the turn of this century.

In a Lisbon slum, the audience is transported toVanda’s room; she is with her sister, smokingand doing hard drugs, worrying about the machines trying to overthrow her neighborhood. The brutality of Vanda’s and the others’ daily lives is complimented by the fictional narrative, which allows us to deeply care about these characters.

By choosing a MiniDV to film a story, whilst leaning over broken down characters and spaces on the verge of destruction, Costa creates a three hour-long epic of meticulous framings, lavish chiaroscuro, and phantasmagoric lights. In Vanda’s Room delivers, to the viewers, the brilliance of Costa’s fiction, while depicting politics that toy with the idea of using bulldozers to take care of a problem, underlining its revelance to Portuguese cinema.

16. Capitães de Abril / April Captains (Maria de Medeiros, 2000)

It took Medeiros thirteen years to make this feature film based on the Carnation Revolution, which ended The Salazar Regime, a right-wing dictatorship that ruled Portugal for forty-eight years.

Medeiros, who is best known as an actress in films such as Pulp Fiction (1994) and various Manoel de Oliveira projects, recreates the most emotional side of the military revolution through the eyes of young captains. While being clearly fictional, it is based on real stories and real people.

Even though it’s flawed structure-wise, April Captains works as an important history lesson; it has stirred up controversy for having such a decisive episode of Portuguese history directed by a woman. Clearly a theme of major importance to the director, Medeiros guides the audience, through the eyes of a child, to best represent the historical Carnation Revolution. Despite initial controversy, the film became wildly popular in Portugal; and, in 2014, it is still being shown in many classrooms.

15. Os Mutantes / The Mutants (Teresa Villaverde, 1998)

Heading back to the characterization of Portuguese teenagers and their environment in the 1990s, there’s this gem directed by auteur Teresa Villaverde. The audience encounters the familiar theme of social injustice and inadequacy—this time from the point of view of three adolescents. They are The Mutants, who are mal-adjusted, live harsh realities, are abandoned by the Portuguese juvenile care system (whilst rebelling against it anyway), and sentenced to a life on the streets.

At first, Villaverde pictured the film as a documentary, but as it was denied by government authoritites, she instead relinqushed a more dramatic look at the subject matter, dealing with other deep-rooted issues such as post-colonial racism, teenage pregnancy, crime, sexual exploitation, and abominable violence. The strength of this feature is Villaverde’s visual talent, including her astonishing compositions and remarkable characters, who are capable of defining an entirely new complex style filled with cinematic lyricism and gloomy colors.

14. Alice (Marco Martins, 2005)

It’s been 193 days since Alice was seen for the last time. Every day, her father Mário leaves the house and repeats the same path he walked the day Alice went missing. His fixation to find her has made him install cameras to monitor street movement, constantly looking for any sort of sign. The obsession has changed him, but keeps him going in the hope that someday he’ll get his daughter back.

The plot itself is a tragedy, but almost as touching is how everything thoroughly adapts in this film. The photography is dark, cold and heavy; the soundtrack (by Bernardo Sassetti) is heartbreaking; and the slow pace complements the melancholy mood. Nuno Lopes, who plays the father, does wonderful work in his first feature film, as does Beatriz Betarda, Alice’sthe mother. Both characters portray two extremely different reactions to the loss of a child: the father with his obsession to find Alice, and the mother with her utter apathy and ultimate breakdown.

13. Vale Abraão / Abraham’s Valley (Manoel de Oliveira, 1993)

As a contemporary alternative to Gustave Flaubert’s novel, Madame Bovary (1856), and adapted from Agustina Bessa-Luis’ 1993 Portuguese novel Valley of Abraham, this film was considered by many European critics to be Manoel de Oliveira’s masterpiece.

The film’s heavy influence on national cinema is evident— it is 3 hours 7 minutes long, includes the director’s literary narration fused with delicate music, is set in the vine-terraced Douro valley (one of Manoel de Oliveira’s favorite landscapes and places to film), and has wonderfully framed long takes and stunning cinematography. Leonor Silveira, the heroine, portrays an elegant and mysterious Portuguese version of Emma Bovary who marries one of her father’s friends. They move to the Valley of Abraham, and when she becomes bored with her marriage, she takes a lover.

Not the easiest de Oliveira film to watch, but worthwhile for his techniques and style. The sub-genre created is based on long compositions and detail only possible in de Oliveira’s work, all of which are emphasized herein.

12. Sangue do Meu Sangue / Blood of My Blood (João Canijo, 2011)

Rita Blanco plays Márcia, mother of two in a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Lisbon. In her divided family, the audience is introduced to her daughter—to whom Márcia is extremely close and wants to stop from following in her footsteps—and Márcia’s delinquent son, who is closer to his aunt (Márcia’s sister) than Márcia herself.

The usual realism in the Canijo’s work, though, surpasses his stories. Most of his style is revealed in the sounds the spectator hears: neighbors arguing, the background noise of the TV airing football matches and “novelas,” the main characters’ own arguments so often overlapping each other’s voices – all incredibly familiar to a Portuguese household. The conventional narrative makes room for characters to grow and become something more important. It underlines the maternal role, the accompanying sacrifices, the courage, and the necessary familial strength—despite all adversities. The tragedy is imminent, but the audience is left with an uplifting message of unconditional love.

11. Os Verdes Anos / The Green Years (Paulo Rocha, 1963)

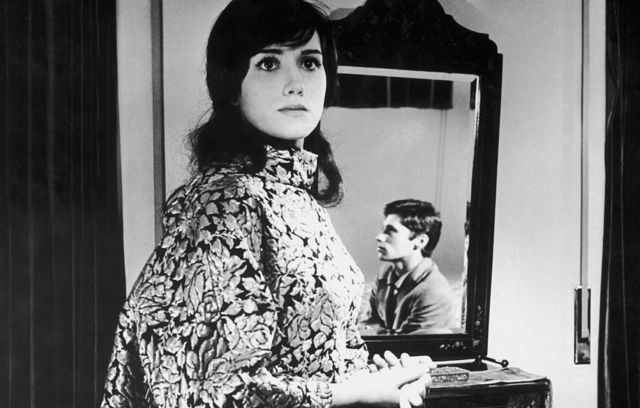

A groundbreaking film in the Portuguese New Wave, The Green Years captured the attention of international critics, who praised this New Portuguese Cinema for escaping the standards set by Portuguese dictator Salazar and the “Estado Novo” (lit. “New State”), which promoted a number of traditional values based on the state’s primary guidelines. The film is significant because of the portrayal—through different points of view—of urban environments, the passage from rural to urban relevant in Portuguese history, the discomfort of inedequacy, and the gradual transformation of Lisbon to a more contemporary capital.

Today, it’s an important piece on what Lisbon was like in the beginning of the 1960s, as wellthe despair of younger generations trying to make a living. It features a wonderful soundtrack by musician Carlos Paredes, known as the master of the Portuguese guitar, whose song “Verdes Anos” became extremely popular ever since. Rocha’s contribution to Portugal’s New Cinema lasted the rest of his life with utmost devotion.