Continuing from where “Akira” left off, “Ghost in the Shell” established cyberpunk as one of the main themes of the genre, and pawned a huge franchise that continues to produce masterpieces. In that fashion, the franchise includes three animated TV series, four movies, and four video games, while a live-action remake starring Scarlett Johansson was released in the United States on March 31, 2017.

Lastly, Kodansha and Production I.G announced on April 7, 2017 that Kenji Kamiyama and Shinji Aramaki will be co-directing a new ‘Ghost in the Shell’ anime production. Its format and release date haven’t been announced yet.

Moreover, it was a trademark of the industry in both its themes and technological advancement, involving a number of pioneering animation processes. Currently, it is considered as one of the greatest anime of all time, having inspired a number of films, with “The Matrix” being among them.

Here are seven reasons that justify the above. Please note that the article contains many spoilers.

1. A complex and meaningful script

Based on the homonymous manga by Masamune Shirow, the anime takes place in 2029, when the world is connected through a vast electronic network that has access to all aspects of life.

Artificial intelligence has become a significant part of everyday life and humans have already installed implants in their heads that help them communicate with computers directly, and in that fashion, are in constant connection with the Internet. The persona of the individual (their soul, if you prefer) that is connected on the Internet is called ‘Ghost’.

However, and despite the vast capabilities this technology has brought, crime always finds a way, and currently, hackers are able to infiltrate actual human brains. These are considered the most dangerous criminals of all. The perfect agent of the era is not a human, but an AI capable of traveling freely in the digital ‘boulevards’ in order to find and exploit any information it can find. This AI was designed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the ultimate anti-espionage weapon, and calls itself “Puppet Master”.

Eventually, the AI decides that it is an actual life form with its own rights and asks for political asylum, revolting against the people that created it, instigating cyber attacks, and at the same time threatening to reveal its illegal creation to the Ministry of Interior, as it also searches for a host that will give it actual physical hypostasis.

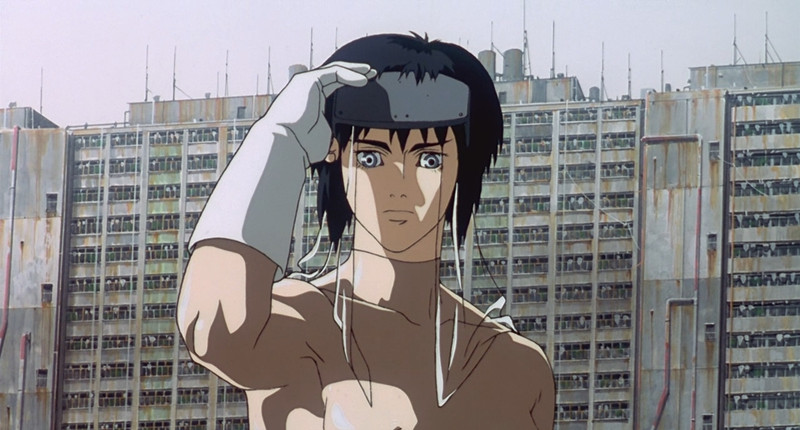

Major Motoko Kusanagi is a highly evolved cyborg who works for Public Security Section 9, an individual branch of the Ministry of Interior. Along with her team of experts, she is on the hunt for the Puppet Master. Soon, however, they realize that they have brought themselves into a battle between the two Ministries, and Kusanagi has to decide if she will let Puppet Master to become a human being.

2. A philosophical background

Although “Ghost in the Shell” thrives on impressive action scenes, there are a number of meaningful comments hiding underneath the action. The most obvious one is the connection between man and technology, and the way it will shape the future.

The film presents a society where technology has made everything very easy and has allowed humanity to evolve enormously, but at the same time stresses the dangers that could arise from the over-dependence on technology. The most important of these consequences is the loss of identity, and the subsequent dehumanization.

This last aspect is chiefly presented through the character of Motoko, whose ghost is the one dominating her body, to the point that it can act completely individually from it. At the same time, the concept of Motoko gives rise to a number of classic sci-fi questions. Can cyborgs have a soul? Do they exist as individuals, since they abide by the specifications of their manufacturer? What does their existence signify?

According to Descartes, Motoko exists as an individual since she is able to think and make decisions. “Ghost in the Shell”, though, questions this theory through the concept of manufactured cyborgs, since Motoko’s thoughts and memories may not even be her own.

3. Pioneering animation highlighted in the action scenes

“Ghost in the Shell” used a novel process called “digitally generated animation” (DGA), which is a combination of cel animation, computer graphics (CG), and audio that is entered as digital data.

Editing was performed on an AVID system of Avid Technology, which was chosen because it was more versatile and less limiting than other methods, and worked with the different types of media in a single environment. Along with the impressive special effects that find their apogee in the “thermo-optical camouflage”, the technical team of the anime managed to present a very impressive spectacle.

This trait is particularly evident in the action scenes, starting with the initial one and continuing up to the end of the film. The one where an invisible Motoko is fighting a terrorist in a city canal is a great martial arts scene in cyberpunk style, and a distinct sample of this trait.

4. The first scene

Major Kusanagi is on the rooftop of a building. She fully undresses, leaving on just a pair of long white socks and her holster with an armed gun. She then jumps toward the bottom upside down and murders her target through the window of the building. As the rest of the bystanders in the room go toward the window, they watch her disappear in front of their eyes.

“Ghost in the Shell” established anime as a genre that did not apply solely to children, and this scene is one of the main reasons, through the nudity and the violence deriving from the grotesque way the victim is killed. As it shocked its audiences, the scene also became one of the most iconic anime sequences ever made. The special effects find one of their apogees in this scene, as the general artistry sets the tone for the rest of the film.

Furthermore, the scene establishes the setting of the whole anime in a number of ways. The first is that the communication is possible through some form of neuro link, as Kusanagi seems to communicate with Batou without moving her lips. As he removes the cables from the back of her neck, four ports are revealed, in a distinct sample of how far technology has progressed in the era in which the story takes place.

The fact that they speak of Section 6 also closing in, in the building, sets her team apart from regular ones, and establishes the base of the conflict between the ministries that rise later in the film. Lastly, her disappearance in the background at the end of the scene highlights the level of technology available to her team.

5. The last battle

The scene where Kusanagi is fighting the tank near the end of the film is one of the most iconic for the style implemented in “Ghost in the Shell”, as it combines impressive action with meaningfulness, since it highlights the difference between ‘Shell’ and ‘Ghost’, in an element that defines the Major’s character.

After avoiding a barrage of bullets from the tank, Kusanagi manages to get on top of it, and attempts to rip the latch off its top, in a truly desperate effort. In her struggle, her impressively muscular body is highlighted, only to explode a bit later into a mass of blood and cybernetic materials. Eventually she fails, and is only saved by Batou’s appearance in the scene, ending up in the ground without one of her arms, and in a truly miserable state.

However, despite the outcome, Kusanagi is not dead, in a fact that highlights the duality of her existence, with her body (the shell) and her mind (the ghost) actually being two different coexisting aspects of her existence. Her body is not ‘human’, but a combination of biology and technology, and thus it can be replaced anytime.

However, the thing that makes her human is her mind, which, as long as it exists, so does she. In that fashion, the scene provides an answer for the existential questions of the film.

6. An impressive combination of realism and artistry

Animation director Toshihiko Nishikubo was responsible for the realism and strove for accurate depictions of movement and effects. The pursuit of realism included the staff conducting firearms research at a facility in Guam. Nishikubo has highlighted the tank scene as an example of the movie’s realism, noting that bullets create sparks when hitting metal, but do not spark when a bullet strikes stone.

Apart from the movement, though, this artistry is also quite evident in the background. The buildings, the streets, the houses, and the various vehicles are drawn in every detail, occasionally presenting images of extreme beauty. For example, in the scene where Motoko is fighting the terrorist, the buildings in the background look magnificent, with a color palette that actually highlights the battle in the foreground through its antithesis.

7. Outstanding Music

Composer Kenji Kawai used a unique combination of Bulgarian folk music with Japanese voices, and in that fashion, managed to perfectly capture the aesthetics of the film, through the haunting but very rhythmic sound of the main theme, titled “Making of a Cyborg”. The entire soundtrack moves in similar tones, apart from “See you Everyday”, a Cantopop song performed by Fang Ka Wing.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.