5. Gabbeh (1996)

Perhaps Makhmalbaf’s most internationally acclaimed film, “Gabbeh” shows a drastic change in direction for Makhmalbaf’s filmmaking. Minimalist, meditative, and pastoral, “Gabbeh” is the first time Makhmalbaf practices silence, and in doing so reaches a poetic new ideal for his filmmaking.

The protagonist of the film is a girl called Gabbeh, who is the personification of a Gabbeh rug: a type of Persian rug woven by nomadic Qashqai tribes. A Gabbeh is woven throughout the seasons, narrating a story with minimalist depictions along its long weaving process.

Makhmalbaf has said himself that “Gabbeh” was his homage to color, and it shows. He shows us how nomadic tribes take the color from nature and dye their fabric. Color is given a history. The sheep fed on greenery, the wool shorn for clothing, flowers boiled for color, and the Qashqai who wear these colorful clothes as an homage to nature.

“Gabbeh” is filled with breathtaking landscapes and the beauty of the Qashqai nomadic tribes.

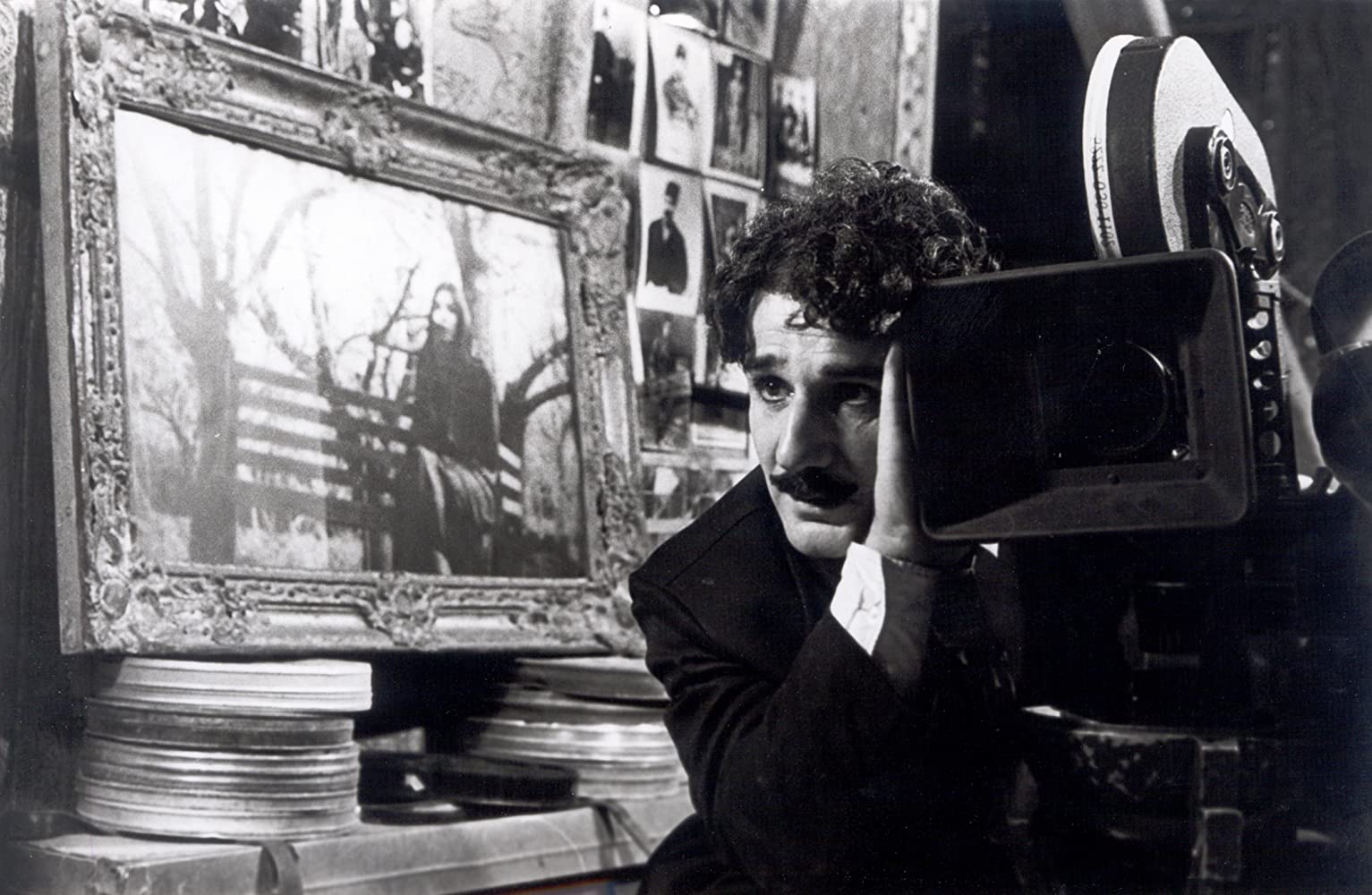

4. Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992)

A true gem of Makhmalbaf’s cinema, perhaps his most ingenious and complicated film. “Once Upon a Time, Cinema” is a historical documentary, surrealist fiction, and shameless parody all at once.

The film begins with real footage taken by Nasir-uddin Shah’s royal cinematographer. Nasir-uddin Shah, the King of Persia in the mid to late 19th century, was a lover of luxury, and the hiring of a royal cinematographer with tax money became one of his hobbies. The film slowly moves from true footage to mock-silent era footage that depicts the fictional affairs of Nasir-uddin Shah’s royal cinematographer.

This film is a microcosm of the entirety of Iranian cinema up to that point; it contains more iconic imagery than perhaps any other film by Makhmalbaf. From blatant self-aware plagiarism to parody to pure cinematic curiosity, “Once Upon a Time, Cinema” is by far the most innovative film by Makhmalbaf, and perhaps one of the most palatable and enjoyable cinematic experiences in Iranian cinema history.

3. Testing Democracy (2000)

Makhmalbaf’s film in the anthology “Tales From an Island,” “Testing Democracy” is to Makhmalbaf what “The Idiots” is to Lars von Trier. Makhmalbaf takes advantage of the radical possibilities that digital cinema can provide to an auteur.

The film begins with camcorder footage of Makhmalbaf struggling to light and direct a scene. Makhmalbaf is called by the operator of the camcorder, and they have a conversation about digital filmmaking in a car ride. Makhmalbaf says how a small camcorder is the ultimate tool for cinematic expression, how it removes the obstacles between a filmmaker and the final product and even helps battle censorship, and how it acts like a true pen for authorship. Makhmalbaf says that with a camcorder, anyone can become a filmmaker.

But the important backdrop of this film is the parliamentary elections of 1999. Through orchestrating some of the most bizarre scenes in Iranian cinema, Makhmalbaf begins to make bold statements about the absurdity of politics.

Perhaps one of the most magical moments of Makhmalbaf’s cinema is his speech aimed at an audience of seagulls. “I regret to inform you I’m leaving the parliament” he says to the seagulls as he recites poetry and criticizes the birds for “not flying well.”

He then fills a motor boat with chalk wall segments and sets sail. In the middle of the ocean, a woman with a ballet box is parachuted down and refuses to let Makhmalbaf vote since he does not have any identification.

“Testing Democracy” is an exercise in filmmaking, a video essay on the absurdities of politics and the power of digital filmmaking.

2. The Silence (1998)

Another one of Makhmalbaf’s minimalist poetic masterpieces, “The Silence” explores the very concept of music. One of Makhmalbaf’s strengths has always been his abandonment of his past ideals for the sake of a purely new ideological experience, and it truly shows how strongly he has changed his scope in order to make this film.

Khorshid is a blind child laborer in post-Soviet Tajikistan, whose landlord is constantly threatening his family with eviction. He has only a few more days to gather enough money to help his mother pay the month’s rent.

The plot is as simple as that, but the beauty of the film lies in Khorshid’s daily travels from his house to his work. Khorshid’s enjoyment of beautiful sounds and beautiful voices often drags him away from where he needs to be and toward the most unlikely locations. In one of the most beautiful scenes in the film, his chaperone lets go of his hand for a moment in the local bazaar, and when she turns around to see there is no chance she can spot him among the crowd, she too closes her eyes and seeks the most beautiful sounds in order to find where he has gone.

Khorshid works in a luthiery and helps the instrument makers tune their instruments. “The Silence” shows the importance of music in Tajik culture, as well as the hardships of child labor, something that comes from Makhmalbaf’s own experience as a child laborer.

The philosophical exploration of music and what sounds we find beautiful and harmonious lies at the core of “The Silence,” a film that holds at least a half-dozen breathtaking scenes in its short run time.

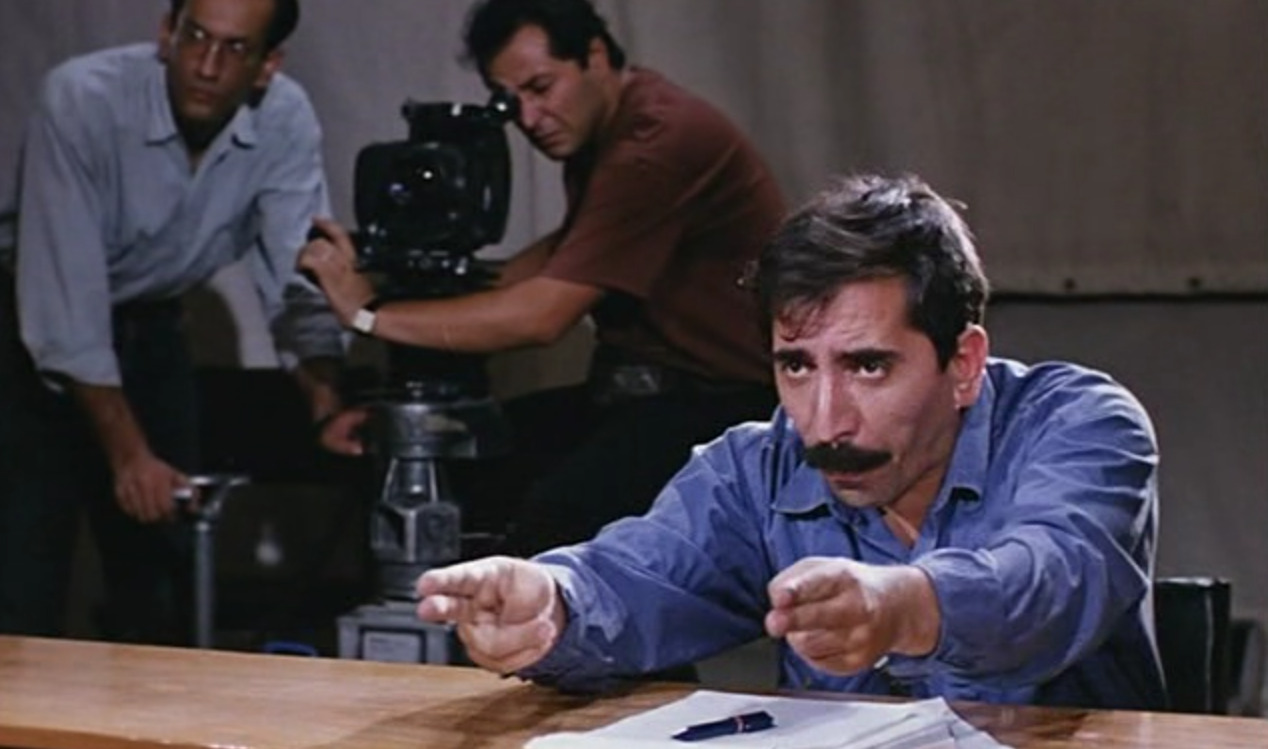

1. Hello Cinema (1995)

The film that acts as a microcosm of Makhmalbaf’s entire filmography and what he represents as a director, “Hello Cinema” is Makhmalbaf’s masterpiece.

As a celebration of the 100th anniversary of cinema, Makhmalbaf puts out a call for actors in local newspapers asking for people with no prior experience in acting to come for a screen test on a specific day. The production team was expecting a maximum of 1,000 people, but a crowd of more than 10,000 applicants can be seen at the opening title of the film.

The applicants are told they are auditioning for Makhmalbaf’s next film, but the caveat is that Makhmalbaf’s next film is the very auditions of the people in this crowd of 10,000.

Makhmalbaf’s questions are simple: “Why are you interested in acting?”, “Would you like to play a positive role or a negative role?” etc, but the beauty is in his manipulation and his injection of drama to each audition. He pits people against each other, and watches them betray their own statements from a few seconds ago in order to simply get cast in a famous director’s movie.

He orchestrates mock group shootouts, asks people to sing their favorite songs, and dissects their reasons for becoming actors. His main screen test is to give applicants 30 seconds to cry. Toward the middle of the film we see applicants angry at being turned down after a 30-second audition. They demand Moharram Zainalzadeh (the main actor from Makhmalbaf’s “The Cyclist,” who is now a camera operator) to go through the same test. The result is tear-jerking. Zainalzadeh begins to cry in 10 seconds, tells how much crying he did for cinema’s sake, how much work he did to be cast in “The Cyclist.”

When two young girls cannot cry on cue, they are adamant about how crying isn’t paramount to the art of acting. They are told to take Makhmalbaf’s place and audition others and we watch them quickly turn down actors who fail to cry on cue.

Makhmalbaf knows how to create drama, and how to weave reality into an elegant cinematic narrative. We see a woman who demands to speak to Makhmalbaf himself; she says she’s in love with a man who has gone abroad, how she needs to get cast in Makhmalbaf’s film to get a visa to go abroad and unite with him. A few years later she will be the titular “Gabbeh” in Makhmalbaf’s film. We see a man who wants to play “good characters” but is always typecast as the bad guy; we see him in “A Moment of Innocence” a few years later.

“Hello Cinema” is an homage to cinema. It’s cinema verite at its purest and most beautiful; the silver screen at its most magical. It’s the epitome of Makhmalbaf’s cinema.

Makhmalbaf is a visionary filmmaker, a philosopher, and a humanist. He believes in the cinema of change and creates works of art that push the audience’s comfort level to its limits in order to make a statement.

His film “Afghan Alphabet” about Afghan immigrants made the government open its public schools and universities to Afghan immigrants for the first time. His films have resulted in legislative change.

Makhmalbaf’s strength is in his insatiable appetite for culture. He has seldom made movies about the same subject and about the same ethnicity. Every single film he has made has explored a new idea, approached from a new lens. His films vary in style, content, and ideologies and though they may not always be the most palatable, they are always guaranteed to be thought provoking.