In 1942, the respected Japanese screenwriter and director Mansaku Itami read a movie script titled A German at Daruma Temple. It had been rejected for filming by Japan’s wartime censors, so it was published in a journal, but Itami was greatly impressed by what he read and predicted the script’s author, Akira Kurosawa, would one day represent the new standard for Japanese cinema. Itami died just four years later, but history soon proved him right when Kurosawa was promoted to the director’s chair and became not only one of Japan’s finest artists but one of the most influential directors of the 20th century.

Kurosawa’s impressive body of work ranges from lightweight comedies to searing masterpieces on the human condition. He made thirty motion pictures, all of which have been ranked below, from worst to best.

30. Dodesukaden (1970)

Even the masters slip once in a while. Kurosawa’s first color movie Dodesukaden represented an attempt on the director’s part to renew interest in Japanese cinema, at a time when domestic audiences were turning to foreign movies and television for their entertainment. Unfortunately, his noble intentions seldom pay off in this grueling drama about life in the slums. Kurosawa once remarked that even a great director cannot do much with a bad script, and it’s certainly true of this film and its excess of unmemorable characters and tedious subplots.

Lesser Kurosawa films usually have striking images and crisp editing to fall back on, but Dodesukaden falls short in this department as well, offering nothing but cheap-looking sets and murky, unimpressive lighting. The result is a visually ugly mess exacerbating an incredibly poor story.

29. Sanshiro Sugata: Part II (1945)

The sequel to Kurosawa’s directorial debut is most memorable as a display of wartime politics. “Highlights” primarily consist of the film’s pure-hearted hero coming to the rescue of his countrymen whenever they’re tormented by American sailors and boxers. One might or might not take issue with such scenes today, but these jabs of anti-western sentiment are sadly more interesting than the film around them.

The main narrative is stale and awkwardly put together, repeating scenes from the original Sanshiro Sugata with less panache, and the only engaging character disappears just when he seems to be making an impact. Kurosawa turned out this sequel at the behest of the studio and confessed years later it had been of no personal interest to him. “This was just warmed-over,” he said.

28. Dreams (1990)

An uneven anthology film reportedly based on Kurosawa’s actual dreams. Some episodes are exquisite and beautiful (an early one of a boy witnessing a fox dance in the forest and later finding a huge rainbow stands out as a highlight). Others, however, are mixed bags and some are even flat out terrible — the low point being a static vignette in which a man finds demons in a grotto.

Interestingly enough, the most memorable episode bears similarities to a dream experienced not by Kurosawa but by his close friend Ishiro Honda (director of many of the original Godzilla movies). In this episode, called “The Tunnel,” a homeless war veteran encounters the ghosts of his long-dead platoon (Honda served in World War II and regularly had nightmares in which he saw the souls of friends who died in combat). Contrary to popular misconception, though, Honda did not direct “The Tunnel” (or any episode in Dreams, for that matter).

27. Madadayo (1993)

Tatsuo Matsumura is excellent in Kurosawa’s swan song, playing an inspiring elderly professor who insists on pushing on with life despite the roadblocks brought about by age. The title loosely translates to “Not yet!”, the catchphrase the professor gives to declare he’s not finished with living.

Madadayo hangs pretty far back on this list as it is about thirty minutes too long and most of the side characters are not especially memorable. That said, it’s still an interesting picture and its final scene is nothing short of perfect: a consummate visual and emotional sendoff for one of the finest directors in cinema history.

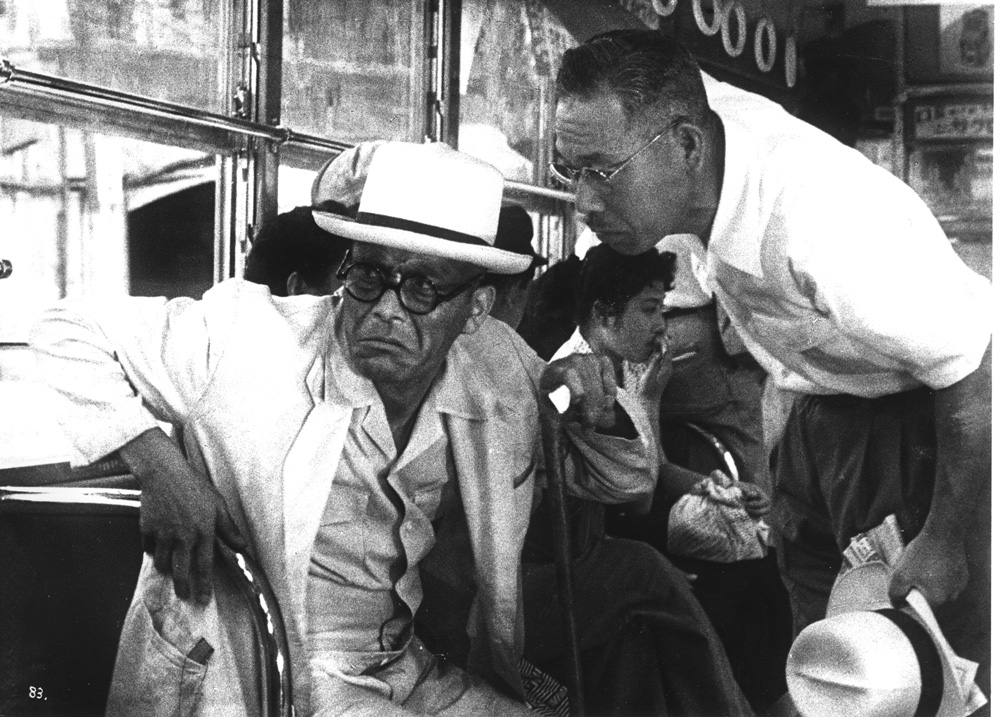

26. I Live in Fear (1955)

Films about nuclear devastation and paranoia had been greatly restricted during the postwar occupation of Japan from 1945-1952. But once the ban was lifted, filmmakers were free to make movies about how they believed nuclear technology had changed the world.

Kurosawa’s I Live in Fear opts for character study, focusing on a seventy-year-old patriarch (marvelously played by a 35-year-old Toshiro Mifune) so afraid that Japan will one day perish in nuclear war that he tries to uproot his entire family and move them to another part of the globe. The old man’s concerns draw mixed opinions from his children as well as the people called in to evaluate his condition. Some think his paranoia is merely a symptom of old age; others don’t necessarily believe Japan’s in danger but still sympathize with his fears.

I Live in Fear is not in the same league as the best anti-nuclear Japanese films (Godzilla, Children of Hiroshima, etc.) but has a number of haunting moments, most of them coming from Mifune. A scene of the old man tearfully begging his children to leave Japan with him is especially powerful.

25. Sanshiro Sugata (1943)

Kurosawa’s directorial debut is a little hard to evaluate given that seventeen of its ninety-seven minutes have been lost. Current copies feature intertitles to help fill in the gaps, but since the missing scenes were key to enhancing character motivations and behavior (and reactions to scenes that still exist in the film), their absence diminishes the film’s power considerably.

Based on what does survive, though, Sanshiro Sugata already shows the technical brilliance and interest in character progression that would define Kurosawa’s best work. He later wrote he had the time of his life making this film, and that’s certainly evident in his energetic direction. A scene in which he indicates the passage of time via a montage (of a sandal carried around in flood waters, later buried in snow, etc.) shows the director was already keen on how to use imagery to tell a story.

24. Scandal (1950)

Even lesser Kurosawa films tend to have fascinating components and scenes of tremendous power. Scandal, a critique of yellow journalism in postwar Japan, isn’t quite as searing as its director intended, yet it still has much to offer through its plethora of intriguing characters — most notably a weak-willed lawyer played by that wonderful actor Takashi Shimura. And let it be said the Christmas sequence in this picture ranks among the finest individual scenes Kurosawa ever directed.

23. Sanjuro (1962)

A clever and amusing follow-up to Kurosawa’s previous film, Yojimbo (1961). In the original, Toshiro Mifune’s wisecracking samurai pitted two imbecilic gangs against one another to wipe them both out; here, he takes a side, trying to help besieged (rather, naive) people take a stand against their persecutors. Having the ronin come to lament violence and cry out in anger whenever he’s forced to pull his sword on another man is another nice touch which makes this a truly worthwhile successor and not just a pale retread.

22. The Most Beautiful (1944)

By 1944, it was apparent Japan would lose World War II. Despite facing imminent defeat, Japanese filmmakers were encouraged to make “spiritist” films: movies showing ordinary civilians dedicated to the national cause. The Most Beautiful is interesting in that it’s not overly sweet or optimistic; it supports the war effort while also detailing the physical and emotional hardships civilian workers went through in showing their patriotism.

The story focuses on young women employed in a war factory as they set unreasonably high expectations for themselves, experience injuries on the job, make mistakes for which they feel guilty, and forge permanent gaps between themselves and their families. Tears are shed aplenty in this film, and more often than not, they are tears of sadness. (Compare this to other Japanese propaganda movies, in which mothers beamed with pride upon learning of their sons’ deaths in battle.)

Kurosawa himself was quite fond of The Most Beautiful, describing it in his autobiography as not a major film but “the one dearest to me.”

21. The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945)

Denjiro Okochi steals the show in this highly entertaining period film. Okochi plays the leader of a group of samurai who disguise themselves as monks in order to sneak their lord through enemy lines. In the film’s most effective sequence, Okochi verbally squares off against an enemy retainer relentlessly questioning him about Buddhist beliefs and practices, Okochi improvising at split seconds to maintain his charade and protect his master.

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was not released until 1952 due to a plethora of political roadblocks — a shame audiences had to wait so long to see this tightly paced (less than an hour long), suspenseful gem.