According to several manuals of screenplays from the United States, a film is divided into three acts. The first: the beginning, the presentation of the film universe that will come to be explored during the duration of the film. The next: the development of a possible conflict presented in the first act; it is where the climax lies. The latter: the ultimate end, an epilogue; in this, the resolutions of the clashes created previously are the key of the moment.

Of course, a movie is fully analysed. But the last impression, the last glimmer, the final glance, is what marks the viewer. Some film endings capture the viewer both by surprise (“The Shining”), by the drama (“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”), by one last sigh (“The Revenant”) or perhaps by the redemption (“Gone with the Wind”).

As classic and melodramatic aspects of cinema, they cherish endings that cause intense and often dramatic emotions. Meanwhile, modern cinema searches for empty endings, reflecting, most of the time, on the inside of their characters.

On this list are dramatic, surrealist, poetic, and enigmatic endings. Here are 10 great movies with powerful endings.

10. The Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2015)

One of the most poetic pieces in the last few years, “The Embrace of the Serpent” is, without a doubt, a masterpiece of Latin American cinema. Ciro Guerra directs with as much propriety and delicacy needed to touch on such delicate points as colonization and exploration.

The movie is about the journey of Theo, a sick German explorer, and Karamakate, an Native, through the the Amazon jungle in a search for a rare and miraculous plant. Forty years later, another foreigner, Evan, takes the same journey with Karamakate.

At the end of the movie, they arrive to a mountain and Evan is able to taste the rare plant. In the moment, Karamakate applies the mixture on Evan, the explorer passes out, and there is a sequence of oniric and hallucinogenic images. They refer to the genesis of the universe, taking the movie away from its previous scenery; also, the camera floats among the mountains, while heavy music and ritualistic whispers can be heard in the background.

The whole movie is black and white, until Even passes out. From this point on, “The Embrace of the Serpent” starts having color, with labyrinth forms that reminds one of a serpent’s movement. Such hallucinations, conducted in a masterful way, gift the viewer with oniric projections caused by the magical plant.

9. Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

One of the only three English-language movies from the director, “Blow-Up” was a manifest of the ‘60s. Fed up of living in an artificial world, Thomas, a well-known fashion photographer, ends up shocked by a photo of a possible murder. Chased by models and by a mysterious woman, Thomas becomes increasingly apathetic about the world he is living in.

The movie ends with a group of mimes doing mimicries of an imaginary tennis match in a park. Under the puzzled look of the photographer, the group keeps playing, until the supposed tennis ball is thrown out of the court. They all stare at Thomas; he, feeling uneasy, goes to the lawn and picks up the ball, giving it back to the mimes. Still observing the match, he starts hearing the ball bouncing on the tennis court.

Here, Thomas is in the middle of a crisis. The monotony of his life took him to the limit; he doesn’t know if the murder really happened or if it was just a projection of his unconscious, striving for some action. He identifies himself with the mimes, who make up actions to satisfy their unexciting existences. When he least expects it, he starts believing the mimes’ fictitious match. When just the crudity of life does not satisfy someone, they try to do something more dynamic out of it, even if it costs them their sanity.

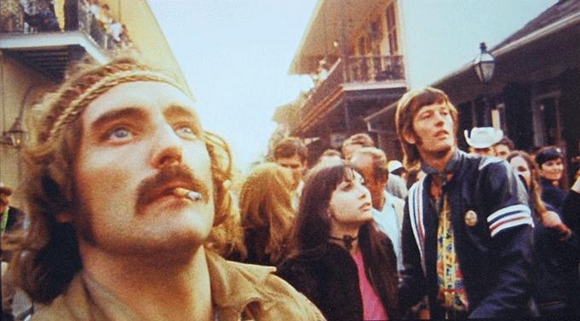

8. Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969)

Dennis Hopper, as well as a very great actor, proved himself a virtuous director by performing his highest work with “Easy Rider.” Placing on the screen a small part of the hippie culture of the United States, the director marked a whole generation of young people who were inspired by the daring and courage of the two protagonists of this piece. Certainly, its impact came together with the fantastic choice of soundtrack, which still echoes in the imaginations of old young hippies.

“Easy Rider” tells the story of two bikers, Billy and Wyatt, who cross the southern U.S. to make a drug sale. Finishing the deal, the two return to travel incessantly through the country as fast as they can to arrive in time for Mardi Gras, one of the most famous celebrations in the world. During their arduous journey, the pair crosses paths with eccentric figures who expose, in their own way, a piece of American society in the 1960s.

Coming to the end of his journey – after acid trips, murder, and involvement with prostitutes – Billy and Wyatt tread their way back. In the midst of this, they encounter two men in a van who, when analyzing their hippie look and non-standards, shoot at the protagonists, killing them. Extremely abrupt, this end is potent and highlights, in addition to the bias of society’s great slice of hippie ideology, the very volatility of human life.

After going through great adventures and transcendent experiences, the two end up murdered by a single shot, fired by a completely random person. Unlike the entire film, Hopper leads the scene with rawness, trying to exploit the maximum amount of realism present at the time, thus making a harsh denunciation against American social organization.

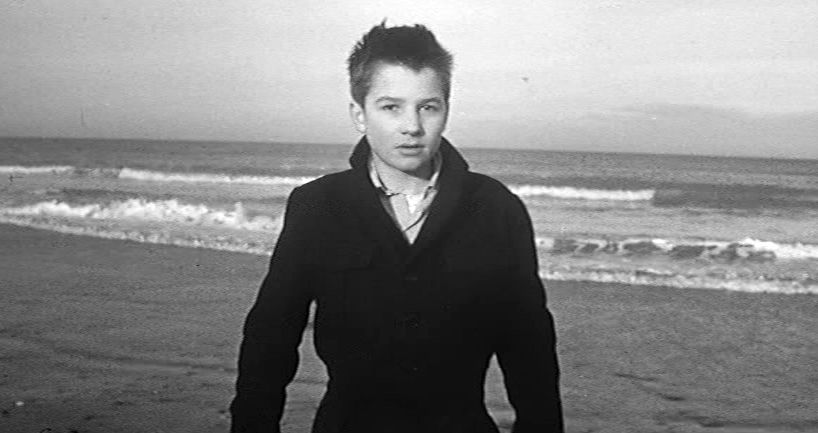

7. The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959)

Alongside Godard, Varda and Resnais, François Truffaut is one of the great masters of the French New Wave. Before becoming a filmmaker, he was a critic and writer of the legendary film magazine Cahiers du Cinema.

During his childhood, he spent much time inside the French Cinematheque watching and analyzing American cinema classics. With that, he created an exceptional cinematographic repertoire that helped him build his virtuous career as a film director.

Considered the opening film of the French Nouvelle Vague, “The 400 Blows” is the most autobiographical film from the French director, with the actor Jean-Pierre Léaud playing Antoine Doinel.

In this film, the young Doinel rebels against impositions from his family and his archaic school education. By breaking family ties and committing small criminal offenses, the boy faces an authoritarian and repressive boarding school that makes him rethink his interpersonal relationships.

Perhaps one of the most iconic finales in movie history. Somewhat simple, the end of “The 400 Blows” shows, poetically and intimately, Doinel running alone toward the sand on a beach. There would be no more perfect scene to close such a work of art.

Here, the loneliness and teenage angst of the protagonists are explored with the famous close shot of Leaud’s face. Running toward the immensity of the sea, the unknown, the scary, the enchanting, Doinel traces his tortuous path.

6. The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973)

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a complete artist: a poet, writer, filmmaker, and actor. Based in Chile but with family of European origin, the director based his career both in Mexico and in the United States.

Working from the absurd and psychedelia, Jodorowsky is considered one of the most megalomaniac filmmakers in history. His utopian project to adapt the iconic book “Dune” counted on several stars (like Salvador Dalí) and a budget completely outside his standards.

The director’s most acclaimed work is, without a shadow of a doubt, “The Holy Mountain.” In this, a thief, with strong similarities to Jesus Christ, walks through a strange and religious city.

Filled with Christian and pagan symbols, the protagonist travels through destroyed scenarios and unimaginable beings. One day, a spiritual mentor – played by Jodorowsky himself – leads him to an enclosure with seven more people, each representing a planet in the solar system. They must ascend to the top of the Holy Mountain and take the place of the Gods.

The end of this maximal work of surrealism is totally the antagonism of what was expected. There is no clash between mortals and gods. There is, however, a clash between film and viewer. Upon arriving on the mountain, Jodorowsky presents a quick dialogue between the master and his apprentices, and then reveals what he least expects in a film: the camera itself.

In a master shot, the entire team is exposed and the entire cast looks directly into the center of the lens. Were the spectators the gods? Or the apprentices of Jodorowsky’s character?