Pessimism, nihilism, misanthropy, and many other terms have already been used to define humanity’s hopelessness about itself and its future. The 20th century in particular was a very specific moment of humanity in which two major world wars, innumerable revolutions and other armed conflicts, as well as economic, social and artistic crises contributed to a hopeless vision of our moment and of what we have waiting for us in the future, whether distant or near in time.

It is no coincidence that, precisely in this very particular century, cinema began to develop with greater force and, as it could not fail to happen, soon the artists dedicated to the cinematic art began to express, through their films, their pessimistic visions about the fate of humanity.

The following list contains films that deal with each of these different levels of despair: the one that comes from the horrors of the war, the death of ideology and religious faith, and pessimistic views on the direction of a society in the face of an increasingly individualistic and competitive world.

10. Naked (1993, Mike Leigh)

In one of his best-known films, British director Mike Leigh tells of the life of Johnny, a nasty aimless, violent, sloppy character who can elicit a series of different reactions in every person who comes in his way. Brilliantly played by David Thewlis, Johnny is a homeless, unemployed, and ill man who, one soon realizes, is in this situation not only because of the complicated economic and social context in which he is inserted, but also out of pure self-will.

The movie bets heavily on Johnny’s dialogue with the other characters to present his arguments, sometimes resembling a true theatrical play. Another theatrical element that Leigh’s film uses well is the manipulation of light, where darkness is sometimes used as a metaphor for both the situation – alluding to what the personagem discusses – as well as the very fate that awaits them all.

“Naked” seems to assert at all times that, no matter how much we are watching decayed and failed characters, darkness will sooner or later come equally to everyone.

9. I Stand Alone (1998, Gaspar Noé)

Director Gaspar Noé continues his short film “Carne” (1991) and returns to work with the embittered and nihilistic butcher who serves as a true spokesman for the most pessimistic and tragic views one can have about humanity. Philippe Nahon plays a butcher from the Paris suburbs who is obsessed with his disabled daughter, Cynthia, and possesses a deadly hatred of immigrants.

If in the short film Noé was betting more on the butcher’s exhausting and empty routine as opposed to some of the injustices and misdeeds he and his daughter were beginning to face, in “I Stand Alone” the director goes deeper into the cruel and sick mentality of the butcher, presenting an existence that borders on the unbearable, both which the character himself coexists with his thoughts, as well as with his coexistence with the rest of society.

The film has long voiceover monologues recited in which the butcher makes a real treatise on misanthropy, expressing the most hateful and cruel things about human existence. One of the most interesting points of the movie is that, as angry as the viewer feels about the butcher’s figure, watching all the monstrosities the protagonist is capable of making, it seems hard not to see, amidst his speeches, an authentic and valid criticism of human indifference to the despair of others, as well as a true call for help.

8. The Devil, Probably (1977, Robert Bresson)

Charles is a young Parisian at the end of his student life who seems not at all anxious about his future. Despite being respected by other students, catching the girls’ attention and demonstrating ease and mastery in most subjects, even teaching some of his peers, he had no enthusiasm about his future, however promising he might seem.

The boy begins to relate to some mysterious characters who share his views of the world, which begins to worry his parents that even with the help of a psychiatrist they cannot change his nihilistic outlook and suicidal ideas. Intent on getting rid of the “vulgarity” of committing suicide, Charles begins to look for someone who can end his life, something similar to what Abbas Kiarostami’s character in “Taste of Cherry” (1997) tries to do.

Robert Bresson’s film is a true critique of the modern standard of living, presenting a somewhat optimistic view of a future permeated by the consumerism, superficiality, and individualism of neocapitalist society.

7. Oslo, August 31st (2011, Joachim Trier)

“Oslo, August 31st” depicts a rather complicated moment in the life of Norwegian man Anders. He is a man in his early 30s who is about to leave rehab to try to resume his life. His first appointment is a job interview, but he takes the opportunity to spend a day in Oslo meeting old friends and family, reflecting on his past and what awaits him in the future. Gradually he remembers past traumas and regrets, and realizes that his remaining options may not be able to help him overcome and continue his path.

Joachim trier’s film is based on the book “Le Feu Follet,” written by Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, as is Louis Malle’s “The Fire Within (1963). It is difficult not to compare the two films knowing this, but Trier’s script has great merit in adapting the French work well to the contemporary Norwegian context. Through his film, we realize how desperate the character’s situation is, no matter how peaceful and welcoming his surroundings are.

The feeling of loneliness and fatigue in following up on existence is quite evident in the movie. As much as Anders finds options and ways to continue, the difficulty of overcoming past mistakes and accepting the future that awaits him makes it impossible for him to move on.

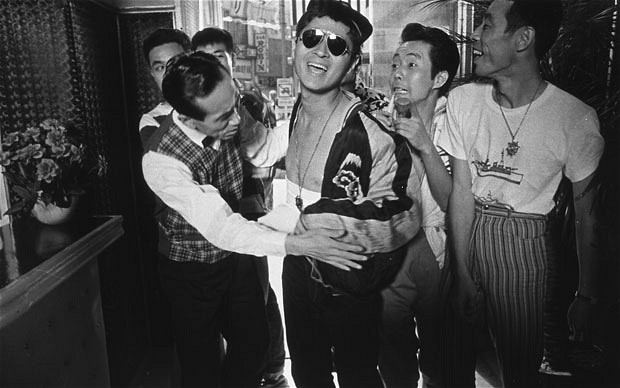

6. Pigs and Battleships (1961, Shōhei Imamura)

Shōhei Imamura is one of the great masters of addressing the bad side of the human being in cinema, but the great thing about “Pigs and Battleships” is that they can bring together a great deal of themes here. Against the background of the years following the Japanese defeat in World War II, the film deals with the hopelessness and horrors of war, the loss of religious faith, the degrading life of the oppressed on the fringes of society, and the decay of ambition.

The film is set in the port city of Yokosuka and deals with the lives of Haruko and Kinta, a couple who must face all the difficulties and setbacks of the postwar moments in order to survive and, as if all the natural complications of the moment were not enough, both end up involved with the Yakuza. Kinta, contrary to Haruko’s wish, turns out to be a mafia pig farmer.

The young man lives with his alcoholic father and spends his days trying to make money at the expense of American sailors passing through town, while Haruko tries to persuade him to change his life. “Pigs and Battleships” addresses the cruel side of man and brings the anthropomorphic metaphor of pigs to represent human decay amidst the postwar sensation of hopelessness and melancholy.