7. Beau Travail (1999)

Loosely based on Herman Melville’s 1888 novella “Billy Budd”, provocative French director Claire Denis’s Beau Travail is almost like a work of black magic. As Salon’s Charles Taylor suggests, “[Beau Travail] is the most extreme example of [Denis’] talent, baffling and exhilarating. I don’t know when I’ve seen a movie that is in so many ways foreign to what draws me to movies and still felt under a spell.”

Recalling his once glorious and full life, Foreign Legion officer Galoup (Denis Lavant) leads his troops in the Gulf of Djibouti. Though strict and regimented, Galoup’s life’s a happy one until the arrival of Sentain (Gregoire Colin), plants the seeds of toxicity. Feeling compelled to stop him from coming to the attention of the commandant who he admires, Galoup’s jealousy will lead to mutual destruction as gender and racial politics meld with Denis’s love of lighting, color, and unerring composition.

“So tactile in its cinematography,” wrote the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman, “so inventive in its camera placement, and sensuous in its editing that the purposefully oblique and languid narrative is all but eclipsed.”

Denis has remained, in the years since Beau Travail, to be one of contemporary cinema’s most audacious directors, and with a ferocious talent to boot. This may well be her crowning glory and it certainly helped closed the decade on a terrific and terribly high note.

6. The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

Irène Jacob proves herself to be the arthouse ingenue of the 1990’s, as well as Krzysztof Kieślowski’s greatest muse in The Double Life of Véronique, which is also a heroic dose of magical realism and visual poetry. In dual roles as Weronika, a Polish choir singer, and Véronique, a French music teacher, Jacob is startling and sublime in the ensuing imitation game.

A fundamental queasiness settles in as a metaphysical/spiritual/existential angle, all Kieslowski specialties, consumes the viewer. There’s mystery and complexity in profusion, all gracefully articulated with Kieslowski’s sensitive eye — cinematographer Slawomir Idziak does his part, too, framing and filming Jacob the way Josef von Sternberg shot Marlene Dietrich, which is to say like a gold-hued goddess — hypnotic and apocryphal as he weaves a mythology in many ways new to cinema.

The plot of The Double Life of Véronique is not an easy one to summarize, but watching it unfold is like watching a rare and delicate flower open to the warm sun, and it’s as fragrant, patient, splendid and exquisite as that comparison suggests. Don’t miss this wonderful movie.

5. Breaking the Waves (1995)

Martin Scorsese cut to the quick when he said: “Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves is a genuinely spiritual movie that asks ‘what is love and what is compassion?’”

1996’s Breaking the Waves was von Trier’s career-defining breakthrough, and the one that announced him to the world as a provocateur and practitioner of auteur-theory.

Much of Breaking the Waves’s staying power comes from the towering performance of Emily Watson who is absolutely unforgettable as the beset upon protagonist Bess McNeill.

Set in remote North-West Scotland’s Outer Hebrides during the 1970s, this heart-rending romance is a saga-like work of histrionic artifice. Breaking the Waves is also a melodrama and an epic of faith, love, martyrdom, and atonement. Gaining momentum and a staggering power by the progressively ruthless, and shatteringly vicious events of the film’s final hour –– which includes Bess being almost supernaturally summoned out to sea by a cruel and sadistic sailor played by a menacing Udo Kier.

Drawing inspiration equally from Carl Theodor Dreyer –– his film Gertrud (1964) is in many ways this film’s template, but the cinematic portraiture and saintly suffering of The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and the raw essentials of Ordet (1955) deserve mentioning as well –– and the Marquis de Sade’s 1791 novel, Justine. Von Trier chooses his influences well, and while moved by them, he also transcends them in many respects.

Righteously troubling, morally unpleasant, and yet unshakably dazzling and deliriously full of grace, Breaking the Waves is an overwhelming and ecstatic experience and the capsheaf of a brilliant filmmaker.

4. Goodfellas (1990)

At a cursory glance it’s easy to overlook the gobsmacking beauty of Martin Scorsese’s tough-talking early 90s Italian-American crime epic, Goodfellas. But working with his holy behind-the-camera pairing of cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, it’s easy to understand how seemingly effortless the lush visuals and dizzying storytelling add up to one of the decade’s most overwhelming and mesmeric viewing experiences.

From the Ray Liotta’s voice-over opening introduction of Henry Hill –– itself a stylistic homage to François Truffaut’s fast-paced French New Wave classic Jules et Jim (1962) –– through to an almost endless array of stylish setpieces (Hill’s backdoor entrance to the Copa, his ill-intentioned meeting with Robert De Niro’s “Jimmy the Gent” that features one of the best uses of “the stretch” rendered that decade [where the camera dolly’s in as the lens zooms out, creating a tense and unnerving framing readjustment], to Hill’s heart-racing, coke-addled third act arrest, Goodfellas gives the audience an endless assortment of visual delicacies.

Gangster films are rarely imbued with as much insight, artfulness, and elegance as Goodfellas, and anything else is essentially just “egg noodles and ketchup.”

3. Three Colors Trilogy (1993-94)

Legendary Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski’s dazzling Three Colors Trilogy will be appreciated by audiences and analyzed and enthusiastically discussed by critics probably forever, and deservedly so. Playfully and profoundly inspired by the colors of the French flag, this daring cinematic triumvirate is as follows: Three Colors: Blue (1993), Three Colors: White (1994), and Three Colors: Red (1994).

And all three were co-written by Kieślowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz (with story consultants Agnieszka Holland and Sławomir Idziak), have musical scores by Zbigniew Preisner, and of course were sensationally directed by Kieślowski. His coup de grâce and final filmic statement, Kieślowski retired after the trilogy, owing to health issues mostly (he died of complications after a heart attack in 1996).

Each film, as their titles suggest, emphasize a different color and emotional spectrum, also playing on the three political ideals in the French Republic motto: “liberty, equality, and fraternity.” And ever the subversive storyteller, each film in sequence have been rightly proclaimed respectively as “anti-tragedy, an anti-comedy, and an anti-romance.”

Assisted by first-rate cinematographers Slawomir Idziak (Blue), Edward Kłosiński (White), and Piotr Sobociński (Red), and of course a female-led dream cast (including Juliette Binoche, Julie Delpy, and Irene Jacob), these films cast a colorful glow that has only added in poignancy and power over the years.

“All three films hook us with immediate narrative interest,” wrote Roger Ebert. “They are metaphysical through example, not theory: Kieslowski tells the parable but doesn’t preach the lesson.”

2. Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

Yimou Yang confirms his status as one of the most masterful and artistic filmmakers with the striking and stirring picture, Raise the Red Lantern. The final film in his loose trilogy that began with 1987’s Red Sorghum, and continued in 1990’s Ju Dou, this is the bleakest of these crimson-hued melodramas.

“People have compared Gong Li and Zhang Yimou to Dietrich and von Sternberg, but for me the Chinese couple is even more impressively cryptic in their design and Raise the Red Lantern is their best,” said actress Isabella Rossellini in a BFI discussion of her favorite films, adding that “…it feels like the history of a country, a culture and even a gender are all present in any randomly chosen frame of this serene and gorgeous poem.”

Filmed in three-strip Technicolor, a process long abandoned by Hollywood, which acquiesces a richness of reds and a luxuriance of yellows no longer achievable in American films, Zhang’s historical heartbreaker somehow sidesteps maudlin sentimentality while still maximizing its titular red blush. One could argue that the flushed palette matters as much as Songlian (Gong Li) does to this wintery tale of stifling coldness and bitter release.

Raise the Red Lantern is more than just a parade of perfectly composed frames, but it no doubt will draw viewers back for those haunting, and heart-shattering visuals. A gem.

1. The Thin Red Line (1998)

Addressing the madness of war from a very theological perspective is part of Terrence Malick’s grand scale sweep in his long-awaited World War II epic, loosely inspired by James Jones’s 1962 tome, “The Thin Red Line”. Taking Jones’s detailed account of of the Battle of Mount Austen, part of the Guadalcanal Campaign, and fictionalizing it in true Malick fashion –– delving and detailing the collective consciousness of the scattered soldiers of C Company, 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry Regiment, and 25th Infantry Division and the exotic and tactile world around them with a painterly perception and a poet’s fevered mind.

“What difference do you think you can make, one man in all this madness?” asks First Sgt. Edward Welsh (Sean Penn), almost rhetorically. Malick’s quest for the meaning of life, refracted and rephrased in The Thin Red Line’s narrative elliptical lingers long in the mind of the adventurous viewer, just as it should.

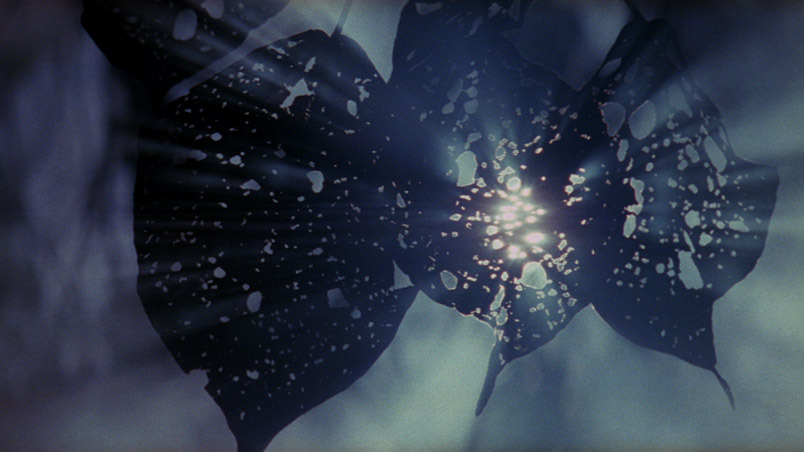

Malick, his cinematographer John Toll, and his editing team of Leslie Jones, Saar Klein, and Billy Weber let frames linger long and languid across colorful wildlife, towering trees, gentle waves, and the play of light that is, on occasion, obliterated by man’s destructive war machine.

As Michael O’Sullivan of the Washington Post wrote, “The Thin Red Line is a movie about creation growing out of destruction, about love where you’d least expect to find it and about angels – especially the fallen kind – who just happen to be men.”

High-minded and heart-piercing, Malick’s movie is never less than fascinating, while also being overtly atmospheric and perhaps philosophical to a fault. While aspects of the film feel confused, even unfinished (Criterion’s 2010 Blu-ray release of the film offers a lengthy director’s cut which rewards the patient with a close to definitive version, and a 5-hour version may see the light of day soon, too), The Thin Red Line remains a monument to artifice and beauty that, as J. Hoberman writes, “thrive[s] on the tension between horrible carnage and beautiful, indifferent ‘nature.’”

A one of a kind motion picture experience that’s not to be missed, few films can compare to the beauty that The Thin Red Line depicts. A classic.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.