In a episode of the animated TV show The Simpsons, son Bart provoked a long series of laughs from his family by revealing that his memory was only seven minutes of duration and he insisted that he wasn’t kidding. The Simpsons, for anyone who knows the show, is a marvel of compression, packing much into a little amount of time. However, it takes some creative individuals much longer to say exactly what it is they want to express.

One problem with creating something which takes a long time to ingest and digest is that the world today is very impatient and quick always seems to be better as far as most consumers are concerned. Admittedly committing to something of long duration takes a bit of fortitude and concentration. Perhaps this is the reason that longer films often have a tough time.

Though there are still exceptions, the heyday of the longer film (which was going strong from the 1950s through the 1970s) seems to be largely over. Modern viewers often don’t have the time nor patience to stay with a long film, no matter the quality. The sad thing is that this attitude often leaves not only the longer films of the present, but the longer films of the past out in the cold.

The titles following on this list are films with long running times and also cinematically rich in one way or another. However, they don’t seem to much get the careful analysis and attention they deserve. The short (yes!) entries here can’t balance that out but might, perhaps, help to raise awareness.

1. Les Vampires (1915-1916) – 417 Minutes

Les Vampires seems to exist under a series of unfortunate handicaps. First of all, the premiere date marks this long, long film as an early silent, a product of a very young period in cinematic art (and many today have no patience with silent films).

Then, there is the length of the film, some seven hours in total (admittedly, since it was meant to be seen in serialized form, this wasn’t that big a thing when it was first presented but there is no way it could ever be presented in that fashion again).

Thirdly, it was all but lost when the last remaining copy was rescued minutes before destruction. Before the advent of home video and streaming, this meant that the film was limited to very sporadic showings.

Then there were the contemporary reviews, which were less than kind (though any cinemaphile knows better than to trust contemporary reviews). Even though there have been a number of film historians offering later day praise, the wild, episodic plot is hard to analyze and take seriously…or is it?

Admittedly approaching a work from near the dawn of cinema requires a change in perspective in order to be able to gain any meaningful insight into the work. In the case of Les Vampires (the title refers to a criminal gang, not any sort of supernatural beings), context helps greatly in understanding the film.

In the earliest days of cinema, films were almost always shot on (usually crude) indoor sets. Louis Feuillade , the writer-director of this and some 600 (!) other films from the dawn of cinema, was famous for taking the camera outside into the real world and filming there.

This may not seem like much of an accomplishment today but it was revolutionary in Feuillade’s day. More to the point, he was very good at blending his actors, playing fictional characters, into the real settings (a considerable trick to this day).

Also, he was filming largely on the fly, creating and revising as he went along. This gives Les Vampires a fast, spontaneous feeling that anticipates the Novelle Vauge by decades. Also, the twisting and turning story of a group of heroes determined to bring the insidious gang (who are quite inventive in their plotting) to heal has left its DNA on film history from Fritz Lang’s spy thrillers down to the exploits of James Bond.

Oh, and the fact that the 1996 Olivier Assayas film Irma Vep, bears the same name as this film’s anti-heroine, is no coincidence. This film may not have Tarkovsky level depth but a careful reading repays the viewer.

2. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) -164 Minutes

Churchill disliked it and tried to deep six it. While being exported to other countries from it’s native Britian, it was chopped to pieces and left in a most unflattering form for decades. It has never quite achieved the popularity of other films by its makers, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, such as 1948’s The Red Shoes. However, the lovely, colorful, comic, thoughtful The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp stands second to none.

The title refers to a stock figure of fun in the UK, a pompous old military man stuck forever in the Victorian era, the great days of the empire, no matter how much time marches forward. The main character, Clive Wynn-Candy (Roger Livesey) is much like that cartoon figure but far more sympathetic.

The film examines his life from the days of the Boer War (the last great stand of the British Empire) through the middle of World War II. Though it certainly has its comic moments, its also a thoughtful, but never didactic, piece on war, peace, the changes each brings on the world and how the individual reacts to those changes and accepts them or not.

Many who don’t give this film deeper thought see actress Deborah Kerr’s playing of three roles (all looking basically like herself) as being an indulgence but closer examination shows that each woman (all existing in their own space of time and never crossing paths) is representative of the Empire at the moment she appears in the film.

Also important is the character of the sympathetic German officer (Anton Wahlbrook), who remains the hero’s friend despite the upheavals of the world and his own greater ability to weather change (he leaves Germany and what’s left of his family with the rise of Hitler).

Sadly, this character and his friendship with the hero was the principal element which upset Churchill, along with what he perceived as a disrespect for the older military traditions (though the film clearly makes the point that the new era won’t respect such traditions). He vowed that Powell would never be knighted (Pressburger, being foreign born, never could be) and he kept it. However, he couldn’t stop this beautiful color production from being a masterpiece.

3. Anatomy of a Murder (1959) – 161 Minutes

Anatomy of a Murder was a big hit in its day and got nominated for a lot of Academy Awards (all lost, mostly to the inferior Ben-Hur). It was groundbreaking in terms of presenting adults themes intelligently in cinema. Why, then, is it somewhat overlooked? The concise answer is producer-director Otto Preminger.

Preminger was a mixed bag as an artist and, reportedly, a human being. While he was one of the two members of the Hollywood elite to break the blacklist (along with Kirk Douglas, both openly hiring famed and long blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo in the same year) and was a tireless advocate against the censorship of films, his routine cruelty towards cast and crew members working on his films was legendary.

More to the point for film scholars, students and fans, his cinematic output was almost as infamously erratic. Even in his studio heyday (mostly at Twentieth Century Fox), great films such as 1944’s classic Laura would alternate with usually a couple of duds such as 1947’s Forever Amber and 1948’s That Lady in Ermine. Those films were made during the period when he made crime thrillers (film noir to later generations) and was fairly stable when put next to the balance of his career when he went into what may be termed his “best seller” phase, making films from popular novels and plays of the day.

However, Preminger’s literary tastes (or just plain taste, period) left something to be desired as most of these films were fair to poor films taken from sources which look quite lacking to the modern eye (1967’s Hurry Sundown and 1969’s Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon are as good examples as any).

However, he did chose one real gem in this bunch. No, not Advise and Consent (1962), though it was based on a dubious Pulitzer Prize winner. It was his adaptation of Robert Travers’ legal procedural Anatomy of a Murder, which was a fictionalized account of a real criminal incident which had taken place in upper Michigan a few years earlier. The crime involved the murder of a local hotelier by an army officer who claimed that the victim had raped and beaten the officer’s wife.

The suspense of the story does not involved who committed the crime (the officer did indeed do that) but how the defense attorney would be able to save the officer from prison and, even more pressingly, what exactly did happen leading up to the crime (there was evidence to support the fact that the sexual aspect might have been consensual and the beating something other than an act of violence by the deceased).

Anatomy offended the propriety of a number of censors and straight laced viewers by honestly discussing rape in an open and honest fashion, as it would have been in a real court (which, of course, it once was). That component has dated a bit but the issues concerning sexual violence and the nature of assault are more pressing than ever and the real theme of the film is the elusive nature of truth and how it often does not at all serve the law.

Due to Preminger’s uneven reputation and the long held perception that the film was once a “hot topic” have kept it from being examined more seriously until lately. The tide seems to be turning, including this film’s introduction into the prestigious Criterion Collection, so its day may come yet.

4. The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) – 265 Minutes

US director Woody Allen may, in fact, have a love for The Sorrow and the Pity, the masterful World War II ear documentary from French film maker Marcel Ophuls, but he truly did it no favor by making it a running gag in his Oscar winning classic comedy Annie Hall (1977).

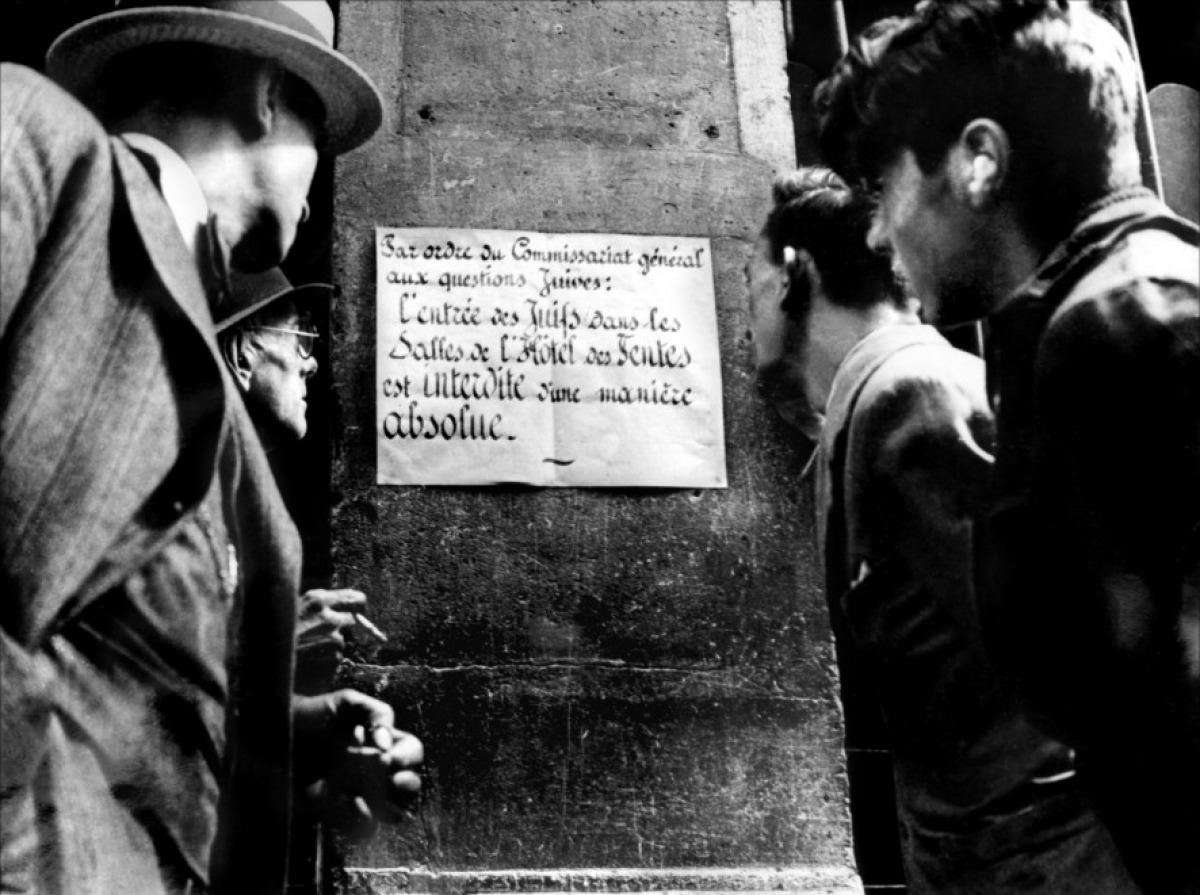

In that film the morbidly joyless Alvy (Allen) obsessively runs to see the film (in a theater in those pre-everything but celluloid times), at one point evoking audience laughs when a few frames of the films (depicting German occupation) flash on the screen.

Added to this is the fact that the film is also the victim of the one of the great injustices in Academy history (it lost best documentary to the now nearly forgotten The Helstrom Chronicles a pseudo-documentary about a supposed insect takeover of the world).

Ophuls, son of the great director Max Ophuls, is a film maker which a great social conscious. All of his films concern large scale injustices and human weaknesses perpetrated on national and international levels. Many of his films concern the conduct associated with Germany and those affected by Germany during the World War II era.

The Sorrow and Pity is chief among these films as it concerns the occupation of France by Germany during that time. However, instead of being a facile piece about bad Germans and heroic French (which is still the norm cinematically, even today),the film indeed details the German’s force and brutality but also the fact that many of the French, far from being heroic, found it much more expedient to go along in order to get along.

Running some four hours and using many interviews with survivors of the time and newsreel footage of the period, Ophuls paints a less than flattering picture of pretty much all involved (which didn’t endear him to his countrymen).

The film also intimidates many who perceive it as long and heavy. It is those things but it should be as its themes of international injustice and the human ability to turn a blind eye when necessary and forget when convenient are important ones, especially when tied to such a vital era in history.

Alvy to the side, this film was too much for many in theaters. The home video era may well be the perfect one to seriously view and contemplate this important lesson from history wrapped in a finely made film.

5. Out 1 (1971) – 773 Minutes

French Novelle Vauge film maker Jacques Rivette has two entries on this list and both are well earned. Until recently, Rivette was considered an also ran when discussions of that movement in film history was discussed. When he had something to say in his films, he was going to take his time to say it and wasn’t going to be rushed.

Also, his plots could seem disfuse at the start of his films and gain in coherence as they go along. This aspect is rather dangerous when dealing with a general audience wanting their films to move swiftly and directly to the point. However, as common wisdom relates, anything worth having is worth working for and, mostly, will require a little hard work. Rivette’s films in general and Out 1 in particular seem to exist to bear this out.

Initially, Out 1 seems to be a meditation on theatrical life. Two theater troupes, one very low budget and experimental, the other well supported by the state, are both preparing productions of works by Aeschylus.

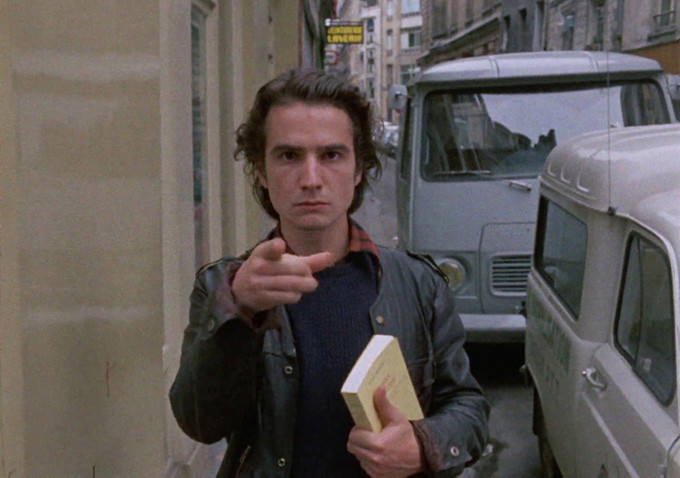

It looks as if the film will concern artistic competition or differing approaches to art but, little by little, unusual characters (such as a young man pretending to be handicapped in order to beg and not for usual reasons) start to appear and the idea of a conspiracy on a massive level, instigated by a group clandestinely known as “the thirteen”, starts to first take shape, then take over the plot.

Both groups learn of the possible existence of these reputedly powerful people (if true they rule Paris at the very least) and the two react as differently to this idea as they do to the idea of Aeschylus.

If all of this feels familiar to fans of Rivette (or those of Novelle Vauge or films in general) that is because Rivette’s wonderful debut film, 1960’s Paris Nous Appartient , has somewhat the same plot. However, at a mere two hours, its just a quickie.

Out 1 was conceived for (and rejected by) French television networks. Under the title Out 1: Noli Me Tangre it was shown in fragments as a work in progress and, when the completed work clocked in at some 13 hours (yes!) theatrical distributors somewhat understandably baulked.

Thus, Rivette prepared Out 1: Spectre, which runs a mere four and half hours (and plays, also understandably, somewhat differently than the full version). Rumors circulated about the full version in cinematic circles (as they tend to) and in 1989, signifigantly after the start of the home video revolution, the full version was finally seen.

Looking over this tortured history, one can sense that the full version of Out 1 happened in stages. It has been written about here and there but many critics, historians, and viewers, are put off by such a long and demanding work. However, once again, anything worth having….