5. Inglourious Basterds – Hans Landa

Back in 2009, many of us went in wanting to see a cool Tarantino flick where Brad Pitt kicks the ass of some Nazis with a team of Jewish bandits. What we got instead was an instant-classic opening scene that followed in the footsteps of Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

Hans Landa is slightly cooky, and he seems charming enough. Once he busts out his large pipe and starts to stare you down, you suddenly are now aware that you are caught in his trap. He knows way more than you wish he knew. He is so quick to hold his targets at a verbal knife point, that everyone knows they are screwed when he turns the tables.

Then the film keeps going, and we are scared to see the guy ever again. He pops up from out of nowhere, and we don’t know if we should be happy to see this enigmatic character or scared because of his power. All I know is that Christoph Waltz’s career in Hollywood jumpstarted overnight thanks to his delightfully terrible Hans Landa.

4. The Dark Knight – The Joker

Duh. Who didn’t see this coming? The predictability only tells half the story for this entry, but we need to take some things into account that we may be forgetting. Sure, the late Heath Ledger’s performance was so damn good that he won a posthumous Academy Award (the Academy usually despises giving big awards of any kind to superhero films; look at the lack of nominations for best picture or director in a year where The Reader was a high contender). The Joker is usually the one Batman villain that is capable of stealing each scene he appears in, but Ledger’s Joker stole the entire film.

In fact, the entire Dark Knight trilogy almost feels like two superhero films anchored around a game changing comic book masterpiece. That kind of power doesn’t come from anyone but the animalistic Joker that is a living, breathing, anarchistic puzzle. I discussed The Hero’s Journey before, but The Joker just does whatever the hell he wants to do.

There is no plan. The structure has been shattered. Having the rug pulled from under you by a revisionist take on an iconic character is so refreshing, especially in a market where rehashing franchises is getting as stale as rotting bread.

3. No Country for Old Men – Anton Chigurh

It is almost impossible to fear Anton outside of his god awful haircut when you look at him on paper. Once Javier Bardem gets going, though, his Hitchcock-meets-Hannibal take is actually nauseatingly scary.

This guy is one of those weirdo vagabonds that you swear couldn’t exist, and yet here they are. You immediately feel in danger once he starts interacting with people. Hell, he kills people for almost no reason at times. His weapons are unlike any you’ve ever seen before (an air pressured gun? Really?), but they are realistic enough to send shivers down your spine.

Chigurh truly is death personified. Nothing can stop him, and his actions are inevitable (outside of the 50-50 shot you get from a coin toss). Most of his victims have no idea what they are in for, either. Sure, we focus on Llewelyn’s fleeing-from-the-scene, and Sheriff Bell’s attempt to keep up, but Chigurh is the cat-and-mouse within the same story that we cannot stray away from. Who will he kill next? How will he kill them?

2. The Third Man – Harry Lime

We finally get an older entry here. The rarity here is because of Hollywood’s former incessant need to have a clear hero figure and a cut-copy villain we are meant to hate. We cannot include films like Battleship Potemkin (with a general group of bad people seen as one core villain), or a film like Baby Face where the lead character has bad tendencies (again, anti-heroes or heroes against type are not being featured here). So, The Third Man is an odd case that is very far ahead of its time, because Carol Reed managed to sneak in a villain we actually care for.

Harry Lime is reportedly dead, and his old friend Holly is trying to figure out what exactly happened. We wait and wait and wait for that big piece of information that can help us solve the mystery. That’s when we are struck with the ultimate switch around: Did we actually just see Lime? He’s alive? He’s Orson Welles?! Suddenly, everything changes.

We, like Holly, have been deceived, and our source of care ends up being the mastermind manipulator of it all. Of course, The Third Man was not the only film of its time to attempt something like this, but it is certainly the finest example, as Welles—who is barely in the film—becomes the main reason to see the picture.

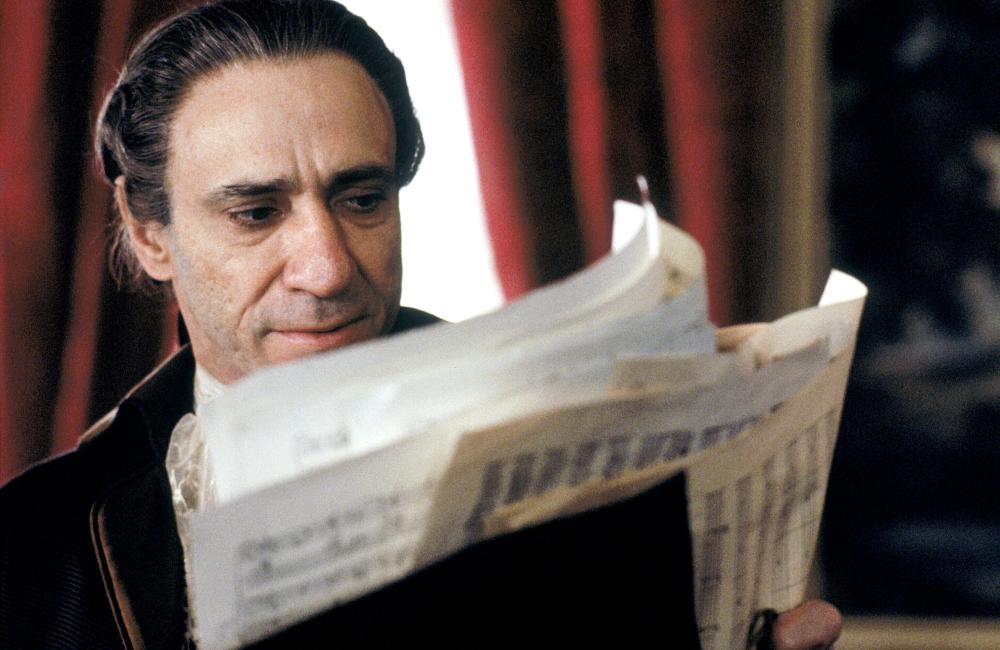

1. Amadeus – Antonio Salieri

It may be difficult to find anyone more suiting of this title. We all love this 1984 Academy Award winner. We adore Tom Hulce as the oddball-yet-perfectionist Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

However, the clear winner of the film is the fictionalized version of fellow composer Antonio Salieri, played brilliantly by F. Murray Abraham (in a performance that is truly for the ages). He narrates the film as a geriatric going senile. He revisits his younger days as an underappreciated musician, and his seething hatred for Mozart grows stronger and stronger. His turning-against God is the ultimate change-of-heart, and we begin to fear where his jealousy will take him.

Do we feel sorry for Salieri? Why not? His work was never appreciated over the procrastinated scrapings Mozart made that people adored (in this film, anyways). Should we hate the guy? Absolutely. He became a monster that tortured an ailing Mozart that needed help. You never know where you fully stand with Salieri, because he is our daily anguish that went the extra mile. We get frustrated when the world doesn’t listen to us. Salieri, in this take on Mozart’s life, did something about it. We can’t agree with his actions, but we, somehow, understand why he did them. He makes us turn on our own morals.

Abraham ultimately won the Best Actor Oscar over Hulce for the exact same film at the exact same ceremony. In a film about Mozart’s (ficticious) life and death, we end up getting Salieri’s rise-and-fall under his fascination and envy of his fellow composer. Salieri is the greatest example of a villain overtaking the hero in a film possibly ever.